In its fifth and final season, Jane the Virgin is still the same show it’s always been. Its pace is just as lickety-split, diving and swooping through one wild plot development after another. Its combination of high-key melodrama with emotional realism makes for the same giddy, tearful, joyful, gasp-inducing storytelling that’s defined the show from the start. After many trials and surprises, after loss and grief and obstacles, after time jumps and villains in sequined eye patches and skeletons buried on the beach and byzantine familial betrayals, in many ways, Jane the Virgin and Jane Villanueva are right back where they started.

That’s true for reasons I cannot and would never want to spoil for Jane fans. It’s one of the few shows on television that not only reliably delivers surprises, but gives the twists enough emotional grounding that they really wallop you across the head, and I don’t want to take that experience away. But as Jane viewers know, season four ended with a mammoth, surprising return, one that catapults the show back into the love-triangle territory that defined much of its first season. It will mean Jane the Virgin spends time on a question that some of its audience may find thrilling, and some exasperating — that’s the way of a good love triangle, and Jane is never a show to shy away from something it knows will stir strong feelings.

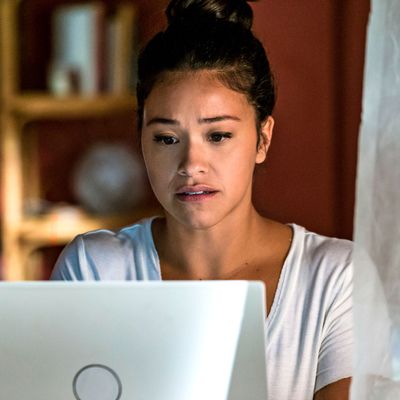

But from what I’ve seen in its first three episodes, the final season of Jane will be a reconsideration of the show’s roots that’s messier and more introspective than a simple return to where it began. The show has always been self-aware. There’s a story in the season’s first few episodes about the writers room for a new television show, and one about equal pay for men and women co-stars, reminding us how Jane has always pointed at its own artifice as a way to negotiate its hairpin tonal shifts. But the self-awareness of this final season works on another level as well: As Jane (the unbelievably talented Gina Rodriguez) considers what she wants for her future, she also has to be honest with herself about how much she’s changed since she first got pregnant, and how far she’s come. Jane does the same thing, deliberately calling back to the beginning of its first season not just to create a sense of fulfillment, but to measure itself against what it once was.

Full disclosure time: Jane the Virgin is a show I have a hard time writing about objectively. I spent several days on the set this summer during the filming of the season premiere. I’ve spoken with its showrunner Jennie Snyder Urman and many members of its cast and crew. It’s a show I’ve thought about a lot over the last five years. My struggle with objectivity has less to do with those specific experiences, though, and more to do with what it’s been like for me as a viewer to watch Jane the Virgin over the past four seasons.

When the show premiered in 2014, I’d just had my first baby a few months earlier, and I remember watching much of the first season in the daze of the sleep-deprived parent, my eyes glued to how bright and snappy it felt. Turning it on felt like being in a dark house and opening a window. I was a part-time adjunct professor at my local community college, and I couldn’t figure out what I actually wanted to do with myself, but I knew it wasn’t that. Jane the Virgin was the first show I was ever paid to write about, and watching Jane Villanueva figure out how to be a mother and have a career at the same time felt surreal to me. Watching the show and writing about it became part of my own balancing act, and to then see that reflected in Jane itself — in Jane’s debates between choosing practicality versus passion, in her concern about how to become a parent — was always moving. Not to mention the show’s remarkable depiction of the mundane specifics of early parenthood, the breast pumps and sleep training and separation anxieties that are now appearing more frequently in shows like The Let Down, Motherland, and Workin’ Moms, but which were much more rare in 2015.

I have never truly felt objective about the show. (I also don’t think that’s a desirable, or even possible, critical goal to aim for; all criticism is written from one person’s frame of reference and it’s silly to expect otherwise.) But Jane the Virgin feels like an especially appropriate show for this kind of relationship. When it’s not about drug kingpins and murder plots and secret identities, or female friendships and grief and romance, it’s a show about the tangled connections between the personal and the fictional. Jane has spent the past four seasons learning how to translate between her own experience and the kinds of books she wants to write, how to balance fantasy and reality, how much of herself she should inject into her work. So much of Jane and her family’s lives have been shaped by telenovelas. From the start, Jane the Virgin has been about a young woman discovering that her own life is turning into a novela. It seems right to watch the show and be struck by the things in it, even in its most absurd telenovela turns, that feel like real life.

What I’m trying to say is that I am too close to this show to offer an emotionless assessment of what it is as it reaches into the homestretch of its final season. But I continue to be impressed with how it balances its many stories, how thoughtful and fully formed each of its characters are, and how it somehow still manages to take unbelievable, impossible plot twists and tie them together so neatly with the dramas of a typical life.

One of my favorite scenes I’ve seen in season five comes in the third episode. After the monumental, existence-altering events of the first two episodes, Jane is sitting cross-legged in a small camping tent, having a quiet, measured conversation with her erstwhile enemy and now sorta friend, Petra. Their conversation is about lots of things: their children, their relationships, how they feel about one another. It is what Jane does best, a conversation that feels true to life, and a preternaturally honest assessment of who these two women are, how much they’ve changed, and what they want to mean to one another. It’s the kind of thing I will miss most of all when Jane’s gone, and it’s what I’ll treasure most while we still have it.