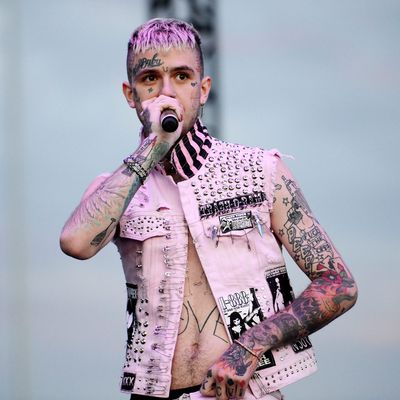

The late rapper Lil Peep took the notion of “bedroom pop” to new literal heights. In the latter part of his short but influential career, the SoundCloud emo-rapper became known for his stage shows, which he would perform from a set meant to evoke his teenage bedroom. The gangly, tattoo-covered, pink-haired 20-year-old would stand before a forlorn twin-size bed and a wall of anime posters while a horde of screaming fans sang every word of his songs back at him.

In the documentary Everybody’s Everything, directors Sebastian Jones and Ramez Silyan make the unusual but evocative choice to conduct the majority of their interviews with their sources in their bedrooms, often in bed. The bedrooms are not glamorous, especially not those of members of the sprawling Downtown Los Angeles collective Gothboiclique, with whom Peep had begun to cut ties prior to his death in November 2017. The walls are dirty, often with crude graffiti etched on them in Sharpie, the bed sheets are unwashed and unmade and the subjects often seem swamped in them. Crumbs and ash and other residues coat Ikea bedside tables and glass coffee tables. Layla Shapiro, a.k.a. Toopoor, Peep’s ex-girlfriend, gives her interview in a gossamer puffed-sleeve gown, half-submerged under a comforter, a forlorn-looking hand-painted Louis Vuitton logo emblazoned on the wall above her. It’s all a little heart-withering, whether you’re familiar with this particular flavor of squalor or not.

For Lil Peep, born Gustav Ahr, the bedroom became a place of artistic and emotional freedom. But it’s also the place where we grieve. Everybody’s Everything makes its festival premiere a mere 16 months after its subject’s passing, and grief still hangs heavy over the film, heavy enough, perhaps, to preclude anything like real objective clarity. The film, executive produced by Ahr’s mother Liza Womack and Terrence Malick, is more emotional than definitive; stopping just short of bestowing sainthood on the artist, but still aiming for something a little more cosmic than reportorial. This is not a “what really happened” exposé of his death, nor is it an academic postmortem on Peep’s musical or cultural legacy. It’s most effective as a character study, even for someone with only a cursory knowledge of Peep’s career, the scene in which it exploded, and the characters that orbited around it.

Everybody’s Everything takes its title from one of Peep’s last Instagram posts. “I just wana be everybody’s everything I want too much from people but then I don’t want anything from them,” he wrote the day before his passing. Throughout the film, we get the impression of a young man who, despite his confrontational physical appearance, was desperate to please, endlessly anxious over the idea that anyone might not be getting as much as he was, or that he wasn’t giving them enough of himself. It elides getting into the symphony of negligence and bad luck that led to his death, preferring to tell the story of a young man who gave so much to his friends and fans that there was nothing left for himself.

The film spends most of its run time tracking the rise of Ahr from his childhood in Long Beach, New York, from a precocious young boy deeply affected by the discord between his parents (his father left their family when he was a teenager, but we learn there was plenty of tension in the house before that), to an aspiring rapper trying to channel his depression into early demos. His work eventually exploded on SoundCloud, leading to his first tour, a move to L.A., and an amassing of collaborators and hangers-on that constantly populated his life and apartment as he recorded his first album. All this takes place within the span of a few months in 2016 — by 2017 he’s selling out shows in Europe, and walking in Paris Fashion Week. And by the end of that year, it’s impossible not to remember throughout all of this, he will be dead.

There are islands of sanity in the nonstop barrage of debauchery and behind-the-scenes footage. Two of them, perhaps not coincidentally, happen to be producers on the film (his mother and promoter/manager Sarah Stennett). But there are others as well — few people come out of the film looking more pure and lovable than ILoveMakonnen, with whom Peep collaborated during his final months. But the most influential may have been his grandfather John Womack, who sent handwritten letters to his grandson throughout his life, offering support and insight through all his trials and tribulations and successes. Jones and Silyan use those letters as chapter-markers of sorts throughout the film, and Womack himself reads them over cut-together childhood home videos and later footage of Peep’s increasingly chaotic life. It’s the most Malick-y touch of the documentary, but Womack is a quietly profound writer — he’s a historian and former Harvard professor who spent the 1960s writing and working alongside Mexican workers’ unions. The contrast of Womack’s words against the fog and flash and copious substance abuse elevate the lurid footage to something more universal.

It’s implied that at heart Peep inherited his grandfather’s socialist leanings and sense of justice. But that impulse was violently at odds with the endless thirst of the attention economy of SoundCloud and social media, where it’s awfully hard to truly redistribute wealth. The nonstop, self-annihilating partying that characterized his final days — troubling to watch but still easier to stomach than his actual Instagram feed could be — was anesthetizing, but it was also his way of giving himself to the people around him. Whether or not this was the actual case or a nice way of thinking of a deeply troubled person after they’ve passed hardly matters; Everybody’s Everything arrives at some kind of truth about the risks and rewards of an artist with seemingly no boundaries, personal or otherwise.