Terry Gilliam doesn’t have an office; he has a lair. It sits atop the London home the Monty Python animator and director has lived in with his family since 1985, and you reach it by climbing up four flights of narrow wooden stairs and through a pair of curtains. It’s the kind of cluttered, magical space where you might imagine a character from one of his films living — a mad professor, maybe, or an exiled king. It’s embellished with Persian rugs and sculptures big and small, and there are books everywhere, on shelves, on tables, and stacked across the floor.

My eyes, however, are immediately drawn to the many props from Gilliam’s movies. There are the figures of Baron Munchausen and Venus, frozen mid-dance, which were used in several effects shots in 1988’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. There’s the black-shrouded Angel of Death from that same film, hanging from the ceiling beside a young Sam Lowry, armored with spread wings, from a dream sequence in 1985’s Brazil. On one table sits the helmet Sean Connery wore as King Agamemnon in 1981’s Time Bandits. Behind it, next to the stereo, we find a miniature of the Crimson Permanent Assurance building, the rogue pirate insurance firm that terrorized the land in the opening scene of 1983’s Monty Python and the Meaning of Life.

At the center of it all is the scruffy, cheerful Gilliam himself, apologizing that he’s on his last day of antibiotics after a recent bout of pneumonia, though he seems quite energetic as he shows me around and points out the props hidden in nooks I might have missed — including the human-faced fish from Meaning of Life, perched on a shelf high above us. “They just throw these away at the end of a movie,” he says, “so I try to keep as much as I can.”

It’s no surprise that Gilliam, now 78, resembles one of his characters; his tales of dreamers doing battle against the forces of conformity have always felt personal for a director who regularly found himself at war with studios and producers. But personal doesn’t come close to describing the bizarre hold his latest film has had on him. Starring Jonathan Pryce and Adam Driver, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, which finally premiered at Cannes last year, is now making its way to screens in the U.S. (On April 10, it will be shown in theaters nationwide as a one-night-only Fathom Events screening. On April 19, it will open in limited theatrical release, as well as on VOD platforms.) Gilliam has been working on it for three decades. Long considered one of film history’s great unmade movies, it has come to define his career in all sorts of unexpected ways, nearly destroying him in the process. Amy Gilliam, the director’s daughter and a producer on his last several efforts, says that for their family, the project has for years been “the dragon that keeps rearing its head.”

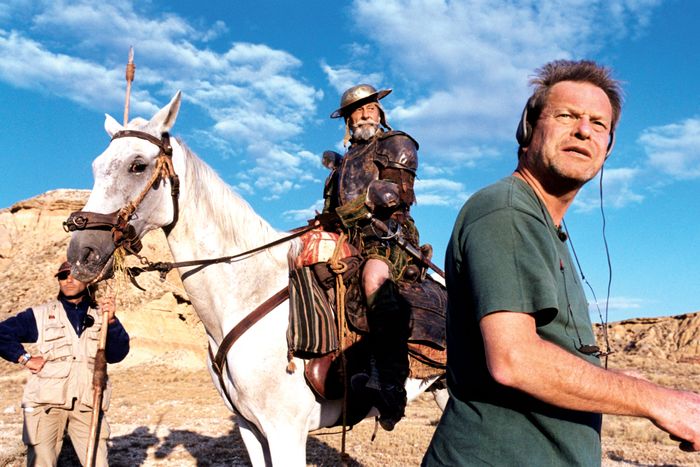

Part of Quixote’s notoriety stems from Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s 2002 documentary Lost in La Mancha, which followed Gilliam’s catastrophic attempt to shoot the film in Spain in 2000 with Johnny Depp and the French actor Jean Rochefort in the lead roles. The documentary, intended initially to be a behind-the-scenes DVD extra, depicts the many calamities suffered by Gilliam’s cast and crew: One location was right next to a NATO airbase, and the roar of fighter jets overhead made sound takes unusable; rainstorms flooded the set and nearly carried off the equipment; Rochefort was immediately diagnosed with a crippling prostate infection, rendering him unable to ride a horse. As the film spun out of control, the insurance company shut it down.

Lost in La Mancha might be a documentary, but it has all the surreal lunacy of one of Gilliam’s own pictures; some viewers even thought it was a scripted narrative. In his 2015 memoir, Gilliamesque, the director recalls that Fulton and Pepe wanted to head home once the production started going off the rails. “‘Just keep fucking shooting, you jerks!’ I had to shout at them from the depths of my encroaching despair,” Gilliam writes. “‘You might not have a film about the making of a movie, but at least you’ll have a film about the unmaking of one, and that might actually be much more interesting.’” (Fulton and Pepe have made a follow-up called He Dreams of Giants, set for release later this year.)

At the time of his 2000 attempt, Gilliam had already spent about a decade trying to make a film out of Miguel de Cervantes’s 17th century novel Don Quixote, about the adventures of a delusional old man who fancies himself a medieval knight-errant. Gilliam first had the idea after Munchausen, and despite the financial disappointments of that film and Brazil, the project was easy to finance, at least at first. “I started with the money long ago. Before I read the book, I called [Oscar-winning producer] Jake Eberts up and I said, ‘Jake, I need $20 million. I’ve got two names for you. One is Quixote and the other is Gilliam.’ He says, ‘Done.’ It was as simple as that.” The catch, of course, was that the novel is more than a thousand pages long, episodic, and surprisingly dense. “I finally sat down and read it,” Gilliam says, “and I thought, Fuck me. Where do we even begin? The problem with all of it was always trying to escape the book.”

Even so, a straight adaptation of Cervantes came close to happening a couple of times; the 1990s were a fruitful period for Gilliam, with such acclaimed hits as The Fisher King (1991) and Twelve Monkeys (1995) to his name. But the director, working at the time with his Brazil and Munchausen co-writer Charles McKeown, had difficulty tackling the story and, beyond that, finding an actor who could bring the right mixture of levity, frailty, melancholy, and naïveté to the part of Quixote. Producers at one point wanted Sean Connery, but Gilliam felt that “Connery was earth, while Quixote was air.”

In 1998, Gilliam started working with his Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas co-writer Tony Grisoni from a new angle. The director had been toiling on an adaptation of Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and decided to merge the two ideas. In this version, the story would follow a young advertising executive, Toby, who hits his head and imagines himself traveling back to Quixote’s time. There, the aging knight-errant mistakes him for Sancho Panza, his faithful sidekick. That was the script that went into production in 2000, with Depp as Toby and Rochefort as Quixote.

Gilliam may sometimes seem like the world’s unluckiest director. His career has been one of fights with producers, runaway productions, and catastrophic bouts of misfortune. Brazil, considered a masterpiece today, found him going to war publicly with Universal Pictures chairman Sid Sheinberg, who refused to release the original version of the film and tried to give it a (hilariously misguided) happy ending; Gilliam famously took out a full-page ad in Variety asking when Sheinberg was going to release his movie. Munchhausen wound up the victim of a regime change at Columbia Pictures, which contributed to an infamously chaotic shoot that went wildly over budget, prompting the insurance company to step in and threaten to fire Gilliam, who then dramatically rewrote several scenes. A hostile Columbia regime then gave Munchausen an extremely limited release, and the film did little business; it is now considered one of Gilliam’s best. On 2005’s The Brothers Grimm, the director clashed with Bob and Harvey Weinstein, who vetoed his choice for lead actress and fired his cinematographer. (Gilliam later admitted that he was reluctant to work with the Weinsteins, but felt desperate in the wake of Quixote’s collapse.) The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009) was thrown into disarray when its star Heath Ledger died halfway through production; Gilliam had to enlist three other actors — Depp, Jude Law, and Colin Farrell — to play Ledger’s character in the rest of the picture, in three different fantasy worlds. The results were surprisingly seamless, although Parnassus itself got mixed reviews. And these are just the movies that did get made.

Many of Gilliam’s troubles, as well as his accomplishments, derive from the particular mix of influences and impulses that have defined his career. He got his start as an illustrator and animator, the kind of artist with a very specific vision in his head of how exactly each frame should look. (In his earlier efforts, Gilliam storyboarded every shot, and was often, he admits, quite determined to make sure that what wound up onscreen was exactly as he had imagined it.) But as a member of Monty Python, he also came to understand the value of collaboration and resourcefulness: After all, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, which Gilliam co-directed, is a movie where, instead of riding horses, characters bang coconuts together to mimic the sound of galloping. At the same time, he’s an independent-minded filmmaker, drawn to disturbing, offbeat subject matter; The Fisher King is probably the most mainstream picture he’s made, and that’s the one in which a steaming, demonic red knight chases the mentally unstable, homeless hero through Central Park. (It’s a romantic comedy, by the way.) Material like this makes Gilliam unlikely to command big budgets. As a result, given his fondness for fantastical stories — dark fairy tales and myths and epic adventures and sci-fi dystopias — he often has to ride every dollar as hard as he can, and then ride it some more.

This can cause problems, to say the least. “Everybody says, ‘Just lower the budget,’ even after we’ve lowered the budget considerably,” says Amy Gilliam. “There comes a point where lowering the budget any further would not allow Terry to make a Terry Gilliam film.”

The story of Quixote’s financing is a winding journey through the peculiar challenges of making one of those Terry Gilliam films. The 2000 shoot was budgeted at $32 million — it would have been one of the most expensive movies ever made entirely with European money — even though it wasn’t quite enough to realize his vision. At the time of Lost in La Mancha’s release, Gilliam expressed hope that the documentary would effectively serve as a feature-length trailer for his eventual Quixote film, but most reputable producers told him to abandon the project. “It had begun to smell like last week’s fish,” he says. “Everybody was telling me, ‘Stop. Don’t keep working on this.’”

But then other, less reputable, and somewhat Quixote-like figures emerged from the shadows, perhaps hoping to become the knights in shining armor who would save the legendary auteur’s dream from cinema’s golden scrap heap of unmade masterpieces. “Each one comes,” Gilliam says, “each one is confident, each one promises, and each one doesn’t deliver.”

Some were, according to the director, well-meaning fanboys who didn’t quite know what they were doing. Others were more mysterious. The director laughs as he recalls one potential producer who approached him sometime around 2014: “She was a woman with an Italian connection, who’d got some money together, which was supposedly the money the President of Tunisia stole when he scampered out of town during the Arab Spring. That involved setting up an offshore company, to get access to this money. But then the money seemed to have moved from offshore Tunisia to somewhere in Switzerland. Then it moved to a new guy who she claimed owned 50 percent of the world’s mineral wealth. And he, for whatever reason now, fancied her. And he was coming over to London. And then he didn’t come over to London. Then he had a heart attack. So he was delayed a bit. Then he suddenly did come to London. But then he decided to run the financing of the film through his daughter’s bank account. I mean, this is getting crazy! We’re talking to people who are doing Skype calls, where pieces of documents are being held up in front of the camera, to show that he was really legitimate.” The director recalls one big dinner, supposedly held to celebrate the final signing of the financing deal with the mineral tycoon. “And of course the next day his lawyer calls and says, ‘That document means nothing!’”

By Gilliam’s estimate, he has made seven honest-to-goodness efforts to get Quixote made over the past 25 years. (The 2000 attempt was actually the third.) Each time, there was money lined up, some semblance of a cast, and a start date. After the abandonment of the 2000 shoot, Gilliam tried to buy back the script from the insurance company and get the film going again. (“I’m planning to start shooting September 25 next year,” he said in an interview in 2002, while helping to promote Lost in La Mancha. “That’s how stupid I am.”) In 2005, he planned to shoot with Depp and Gerard Depardieu. By 2009, Robert Duvall was considering playing Quixote, and by 2010, Ewan McGregor had replaced Depp. In 2014, John Hurt was announced as the new star, with Jack O’Connell lined up to play Toby. “That was a good moment,” says Gilliam, gesturing out the window. “I still have the tapes of John and Jack in my garden rehearsing stuff.” He’s wistful about the fragility that Hurt would have brought to the part. “He would have been a small man’s Quixote,” Gilliam says. “His face, his voice. He wouldn’t have been as funny or as mad as Jonathan, but he would have been more tragic. Just a couple of lines that he said, I thought, Fuck. This is brilliant.”

In June 2015, Amazon joined the project as a distributor. Early the next year, Amy Gilliam recommended that Terry meet Driver, fresh off the success of Star Wars: The Force Awakens. The two hit it off and Driver signed on to play the part of Toby. Things finally seemed to be going Gilliam’s way. But just as cameras were ready to roll, Hurt announced that he had pancreatic cancer. (He would die in January of 2017.) Out of respect for his friend, Gilliam waited to recast the film. Despite the dire prognosis, he says, “I wouldn’t even consider looking at anybody else. I delayed everything for six months.”

Next, Gilliam’s fellow former Python member Michael Palin was cast as Quixote in 2016, around the time Portuguese producer Paulo Branco came on board. Though he has a long list of credits, Branco turned out to be another one of those flamboyant, larger-than-life figures promising more than they can deliver. According to Gilliam, in the four months Branco was involved with the project, he demanded creative control and attempted to slash cast and crew salaries, alienating Palin and eventually driving Amazon away. When the producer failed to deliver on the financing he promised, he and Gilliam hit an impasse, and the producer canceled the shoot. “We were all either in cars heading to the airport or actually at the airport ready to fly to Lisbon when Paulo pulled the plug,” Gilliam recalls.

Money had already been spent and sets had been built, so the director kept going. “We had to put the whole thing back together in about three or four months,” he says. With Palin gone, he contacted Pryce, who, Gilliam says, had been waiting “patiently in the wings for 15 years.” Pryce had starred in Brazil and made three films with Gilliam before Quixote but had never felt old enough to play the character — now, finally, he was. (In earlier versions of the project, Gilliam had considered casting him in a smaller supporting part.) The actor remembers receiving a text from the director in the middle of the night. “It said something like, ‘Well, I suppose you’d better do it, then.’”

But Gilliam was still $3 million short. Miraculously, Alessandra Lo Savio, a producer friend of Amy Gilliam’s, offered to put up the money. Elated, Amy and Terry went to meet her.

And then Terry Gilliam had a stroke. “Amy was driving me back home and suddenly pulls out into the middle of the road,” he remember. “I said, ‘What are you doing?’ She said, ‘I’m going around that bus.’ And I said, ‘What bus?’” Terry hadn’t felt anything, but doctors confirmed that a blood clot had hit his optic nerve and taken out part of the vision in his left eye. “So I’m less of a visionary director now,” he jokes.

In some ways, he had to be. The final budget of Quixote was about half of what the 2000 shoot would have cost, partly due to changes in the script over the years. “We stopped thinking of Quixote as a story set in the past and started thinking of it as a contemporary one,” says Grisoni. He notes that this version of Quixote is in some ways darker than what they set out to do many years ago. “The contemporary world, the world of Tony, is harsher and crueler than it used to be,” Grisoni says. That was in part simply the by-product of getting rid of the time-travel element — things are always more lighthearted when someone gets bonked on the head and goes back to the 17th century — but also a reflection of Gilliam’s own frustrations at what he sees around him. “I’ve reached a point with the modern world where I don’t know what to make of it,” the director says. “I do not. Pandora’s box has been opened, and we are living in a time of chaos and madness. From Trump to Brexit, this is madness!”

That sense of helplessness and despair runs throughout the finished film; the characters are all ultimately at the mercy of wealthy, cynical oligarchs and those who serve them. This matches rather well with Cervantes’s caustic, surprisingly modern portrait of class and aristocracy. Meanwhile, although Gilliam had initially seen more of himself in the romantic Quixote, he gradually found himself identifying more with Toby, who in the film’s final version is no longer an ad exec but a filmmaker who has squandered his promise and become a director of commercials. During a shoot in Spain, he discovers a DVD copy of his thesis project, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Making a brief trip to the small village where he had filmed it a decade earlier, Toby finds the place in disarray; it turns out people’s lives were ruined by his little shoot. Most notably, Javier (Pryce), the old cobbler he had enlisted to play Quixote, still believes himself to be Cervantes’s knight-errant.

The theme of Toby’s guilt — and the corrosive, mind-altering effect that movies can have on people, much as books of chivalry did on Cervantes’s “imaginative gentleman” — was something Gilliam insisted on as he and Grisoni rewrote the screenplay. “A film crew, we’re like Vikings,” Gilliam says. “We’re pillagers. Or locusts, maybe.” He recalls shooting Monty Python and the Holy Grail in a Scottish village in 1974. “Marriages break up, people come running down to London trailing after us, all sorts of shit went on. A film is like a bad disease. I thought, Let’s play with all of that.” He remembers one man during Holy Grail who took a bus to come up to Scotland to work on the picture. “He paid his way up there. He just arrived on set one day and was like, ‘Can I be in the movie?’ And he was wonderful. He doubled Graham [Chapman] for a while. He was doing stunts that other people couldn’t do. That’s the siren call of cinema. Some people crash on the rocks and drown. Other people take off and fly.”

It could be argued that Gilliam has done a bit of both. The final shoot of Quixote was remarkably smooth. Many of the locations were the same ones he had shot in (or planned to shoot in) back in 2000. “Nature for once was kind to me,” he says, though he notes that a rainstorm did hit toward the end, during a scene that required fireworks, and briefly flooded the set. But mostly, Gilliam’s challenges had to do with the project’s overwhelming legacy. He admits he was initially terrified that “it wouldn’t be as good as I’ve been dreaming it — and even worse, that it wouldn’t be as good as other people have been imagining it.” One pleasant surprise was Pryce, usually modest and reserved, who turned out to be quite the showman. “Jonathan’s a great comedian, and Quixote deserves humor,” Gilliam says. “When we were shooting, I said, ‘John, it’s like you’re playing every Shakespearean character you’ve ever played, all in this one figure. He brought so much madness, arrogance, sweetness, and humor — I thought he exploded when he arrived on set. He’s a great ham.”

But, of course, this is Gilliam, and nothing he does is ever easy. The feud with Branco landed in French courts in 2017, and the producer tried to stop the film’s Cannes premiere, claiming the movie was his. A judge ruled in favor of Gilliam, but at Cannes the film was preceded by a disclaimer saying the festival screening did not “prejudice” Branco’s claim to the rights of Quixote. A month later, a Paris appeals court ruled in favor of Branco, after which the producer claimed he owned rights to the film. Luckily, it turned out that all the decision required for the film to be released as planned was for Gilliam to pay Branco $11,600 in damages.

But the legal problems took their toll. Just before the Cannes premiere last year, Amy Gilliam noticed that something was off with her father. “Your whole left face has dropped down,” she told him, though he hadn’t felt anything. Another medical checkup confirmed that Terry had experienced a blocked perforated medullary artery. Reports suggested he had suffered another stroke, but he insists that’s not accurate. “There’s been a blockage of things, but I seem to be okay,” he says. Either way, he (and the film) made the premiere as scheduled, and the director danced and joked with his cast down the red carpet and up the stairs to the Grand Théâtre Lumière before finally raising his arms in triumph. At the end of the screening, the Cannes audience gave him a 10-minute standing ovation.

Back home in London, Gilliam fires up his computer to look at some marketing images and then at Facebook. (He writes almost all of his own posts, in case you’re wondering.) As Quixote has slowly made its way through theatrical releases in Europe, he has gotten some good reviews, though he’s still not sure how the film will be received in the U.S. And with the finish line so close, he admits he isn’t entirely sure why he found himself unable to let the project go. “I hate people telling me not to do something,” he says. “I’m still like a kid who won’t listen to his betters. I can be perverse. I can be obsessive. Why does Quixote himself keep getting up? I don’t know. I can’t explain it.”

*A version of this article appears in the March 18, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!