In the second season of HBO’s Barry, things are really looking up for Barry Berkman.

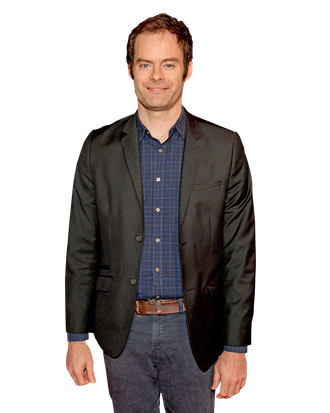

Just kidding! Life is pretty much still a mess for the recovering hit man and aspiring actor played by Bill Hader. He’s forced to transform NoHo Hank (Anthony Carrigan) and his band of Chechen boneheads into brutal assassins. He’s lied to Gene Cousineau (Henry Winkler) about his past. And his attempt to leave his murderous past behind has backfired royally, resulting in more casualties for which Barry bears responsibility.

Hader, who co-created the series with Alec Berg (Silicon Valley), spoke recently via phone about the development of this even darker season of Barry, the relevance of this season’s Afghanistan flashback, and where the series may go long-term. (After this conversation, HBO confirmed that it has picked up Barry for a third season.)

When you were writing the first season, had you mapped out a longer arc for the story that you imagined extending into a second season? Or were you not sure at that point whether there was going to be a second season? When I watched the last episode of season one, I felt like this could easily be the end of a stand-alone season or it could go further.

No, we always thought it would go longer, but we didn’t know super-specifics. It’s kind of like little milestones that are in our head, you know? Alec and I just kind of will go, “Oh, it’ll be interesting if this happened and down the road this happened.” But we didn’t have it super, super mapped out. We didn’t know what season two was going to be until we started writing it.

How much of the writing process is done together in the writers room and how much is it writers retreating to their offices to do their own work?

We usually start before the writers room starts. I will get an office and I sit down, and I just come in every day and start thinking of a possible scenario of where the show could go. And Alec will come in and we’ll talk about it, and then we come up with a structure for the season.

Basically, you just want to be wrong fast. You want to put it up in front of the room of five other writers and go, “What do you guys think of this?” And they pick it apart and say, “Wouldn’t this have this?” Or, “I don’t even care about that guy.” That at least gets a conversation going. These ideas that you’re kinda holding on to that you think are so important are usually the ones that people go, “I’m not into that. But a little part of that — actually, you know, this thing about Sally’s ex-husband, that’s interesting. That should be a part of this season,” where in our initial version it was just something that was very peripheral. Then a writer will be like, “Isn’t that important?” Then you start talking and a writer will say, “Wouldn’t it be interesting if Barry had to teach the Chechens how to shoot?” That’s a great idea, and that goes up on the board.

Basically, what I do is, I put eight columns up on the board and then I just start throwing these ideas into each column. So we might talk about Fuches’s tooth. That would go in the first one. And then Barry teaches Chechens, that’ll go in the third column. Eventually, each of these columns has a structure, and then we give that to a writer and they’ll write up a script. Then we come in and we read their draft, and then they go back and they do some notes and then they give it back to us. Then Alec and I take that and we do a big rewrite on it because, in production, as we’re doing the table read, things start to morph and change, and on this show if you change one thing on episode one that has a massive ripple effect.

This season, Alec and I were doing a lot of writing on set where it was like we would be shooting episodes one and two, and Alec and I would be writing three and four. And then while we’re shooting three and four we’re doing big rewrites on the next two. We didn’t do that for season one because season one, I feel like the scripts came together pretty tight, pretty fast. It was pretty, “Oh, I get where all this goes.” Where season two is a little different. And I think some of that is because I went and shot It 2 in the middle of the season and Alec was doing Silicon Valley and there wasn’t a lot of time.

NoHo Hank has a bigger role this season. How much of that was due to the fact that the actor is bringing something to it that maybe you guys didn’t anticipate when you were originally writing that part?

Oh my God. Yeah, no, he died in the pilot. That’s what was written —

Is that right?

— Is that Hank was killed, yeah. And Anthony [Carrigan] was so funny that we were like, we can’t kill him. One of the first conversations Alec and I had when they picked up the series was like, “All right, they picked us up. We’re not killing Hank, right?” It’s like no, no, no, no, we’ve got to figure that out. There’s no way. And then the first day of writing with our writers started off, “We’re not killing NoHo Hank, right? Because that guy, what a character.” That is so much just based on what Anthony did with it.

The fact that you’re so involved in the writing process and then in some cases the directing process as well, does that help you as an actor? Do you feel like it gives you a better understanding of the character?

To me the acting is the most instinctual part and I would love to get that way with directing, where it can be as instinctual. But it’s hard to be instinctual when you’re directing because there are so many variables to it that you’ve gotta preplan when you’re trying to shoot stuff on as tight a schedule as we have, you know? As TV goes, our schedule is not that tight, but it’s still tight where you can’t be like, “Wouldn’t it be great if …?” You can’t really. You’ve gotta say “Wouldn’t it be great if” three days ahead of time and be ready for it.

As an actor, it’s nice to know where the story’s headed and where the story is and where we’re at. As a writer, it’s nice to know what the emotion is in that part of the story and where we’re headed. A lot of times as an actor you don’t know those things and you’ll play something, and sometimes a director doesn’t know how to tell you “I don’t know if this moment’s working” because the emotion’s not really right. That helps, but really, I barely know my lines. I’m doing all the other stuff, then when it’s time to act it’s like, “All right, wait, what are we doing?” You know what I mean? In a weird way I think that helps me because I’m just being much more instinctual about it, and the only thing that sucks is if I will kind of modulate or approximate my lines. The people who are more theater-trained tend to get a little frustrated with me, I’ve found, because I kind of dance around the whole thing. But I just like behavior. I’m more interested in behavior rather than the exact words they’re saying.

In some ways it must be kind of helpful to approach it that way because then you’re not overthinking it.

Yeah, that’s the death, when you overthink it too much. But then again, there are great theater actors and great actors who — I never went to a real acting school, and they do think about it and they do a ton of work and they’re phenomenal. You know? But I came out of improv and that’s the whole thing with improv: Don’t think, and make the other person look good.

As an actor, have you ever come in contact with a Sally? With somebody who is that precious and self-involved?

Yeah, but not just women. Alec and I talked about that character as not just a woman, men, too, you know? It’s a type of actor. Not even all the time actors. Sometimes we’ll talk about things that we put into Sally that are, like, a musician friend or someone you just met on a set who was a producer. It’s a lot of narcissism in Los Angeles.

That was the cool thing about being on Saturday Night Live. You get to see all of these people come in who I thought were really awesome. Like Justin Timberlake shows up with, like, nobody, it’s just him. And he’s like, “Where do you want me?” Then you’d have people coming in and they would have giant entourages, and they would, you know, tell us how to be funny and stuff.

Who had the biggest entourage that you can recall?

I don’t remember. I guess a lot of them. They all had about the exact same size entourages.

Was Justin Timberlake the only one who came in without one?

No, no, no. Most people at SNL, they would come in with — like when I hosted the last two times, I had my assistant and my publicist with me. That’s most everybody. And Justin Timberlake had that, too. I’m just saying for someone who is as famous and is such a global pop figure, you’re like, “All right, get ready. Timberlake’s gonna come in with a bunch of people,” and he’s, you know, having a Coke by himself like, “Hey, what’s going on, dude?” You know? It’s like, whoa! Where some people, especially musicians, it’s like you gotta go through eight levels of people to say, “Hey, how’s it going?” Or, “We have a note for you on this sketch,” or whatever.

On that note, because you guys write so much about the narcissistic quality of acting, do you find yourself more self-conscious about potentially becoming that way yourself?

You can’t write it unless you’ve seen it or have felt it in some way. Most of the stuff Sally does I can’t relate to, but I think a lot of what helped me writing it was, it all comes from insecurity and the fear of, I’m out here and this might not work.

Also Alec and I, especially, just considering Sally’s character was abused. I don’t know what that’s like. Alec doesn’t know what that’s like. So we talked to a lot of people. We talked to a lot of women, who either had had this happen before or who know people who had this happen before, and we’d show them these Sally scenes and go, “Does this make sense?” I think Sarah [Goldberg] as well was super vigilant of, “I want to make sure that this is about her, like this specific woman.” This is what her values are, and she’s not speaking for everyone, which was, I thought, really smart. A good actor will bring you that. Sometimes as a writer, you think on a global level, and I think Sarah was really smart and tactful in the way that she wanted to handle it.

You directed two episodes this season, episode five and the finale. What is it about those episodes that makes you go, “I want to direct those.”

Well, episode five was just a thing I saw very clearly. It’s a very visual episode. And then episode eight was our finale — it’s certain things you connect to. I remember there was a sequence in episode seven that Alec really connected to that happens with NoHo Hank and he was like, “Oh, I really want to do that.” To be honest, if we do it again, I think I or Alec would direct the first couple because Hiro [Murai, who directed the first two episodes of season two] had a really rough time. I hope he had a great time because he just does amazing work. But it is always hard for the first episode back to be directed by someone who isn’t the showrunner.

Hiro is such a genius and someone that you can do that with. You can just hand it over to him and go, “Well, clearly you know what you’re doing.” But you can only really do that with someone of Hiro’s caliber. Because it’s kind of like handing them a piece of paper that says, “Read my mind.”

The flashbacks to Barry’s first kill in Afghanistan have been really important this season. Can you talk about why you felt like you needed to have that flashback?

The idea behind it was that we knew we wanted to show his first kill and we thought it would be really interesting if … from the kind of documentaries we were watching and books we were reading about guys at war, you know, they had to detach themselves a bit, and it was like, that could have been a source of camaraderie and a source of community [for] Barry. We’ve established, okay, he was born good at this, so we should show the moment when he realized how good he was and how him being good at killing could be a form of acceptance. So it was very thought-out. I think it was always that it would be a sniper thing; we would never see who he was killing. You know, it’s people who were, like they say, 700 yards away, and it’s just detachment to the suffering that the people are going through, and he is kind of realizing that. And then having the class act out the scene, kind of showing how they would react and how possibly he should’ve reacted.

Initially, we had that in a later episode, that moment, and Alec Berg was smart enough to say, “I think this should go in episode one ‘cause the more we talk about it, it seems like a great jumping-off point for him for the whole season, the thing that sets him off-balance.” You know, last season, that’s in the past — I kill for money, but I can put it behind me. And then to have a memory, to have a thing be buried and come back, and have a realization of, Oh, no, the first time I killed someone was the first time I ever felt accepted. This is much more ingrained in me than I thought.

As far as the flashbacks are concerned, [in the] first season we had these daydreams throughout the season and it was this idea of, I could have a better life, or maybe I could just be normal. And season two, we felt like instead of just doing that again, it was, “Well, in order to have that, you have to kind of reconcile your past, so let’s have flashbacks. But not have a lot of flashbacks.” Initially, we wrote a lot of flashbacks to different times in Barry’s life and it just got really confusing. So let’s just focus on a small number of them and relate it to a very specific incident.

I feel like normally when you see that kind of first-kill flashback in a film or a TV show, it’s detachment, but then there’s this immediate sense of, “Oh, God, what have I done?” And guilt. In this case, it’s not really that. It’s almost, like you said, a joyful experience.

Yeah, you know, Hiro Murai and I talked about it, like, “He just hit the highest score on Asteroids.” He’s in a video game. We should shoot this and think of this as, “They’re not at an OP in Afghanistan; they’re at an arcade. And the new guy just got the highest score on Street Fighter.” And everybody went “Waaaaaah!” and all the new kids, the older kids at school, are like, “That was amazing.” You know what I mean? That’s how it should be treated.

I’m wondering, how do you and the other writers decide what’s too dark? Like, are there things that you were thinking about doing this season and then you said, “Hmm, that’s maybe pushing it too far.”

Yeah, I mean, there are things that you go — it’s not that they’re too dark, as long as it’s honest. The thing we usually try to draw the line at is something that might feel gratuitous, as far as violence is concerned. It’s always trying to keep the gore factor to a place that’s much more — I’d rather be shocking. And later in the season there are some violent things that can be construed as funny, but I don’t think the violence itself is funny; I think the people perpetrating it or the situation is funny. You know? But as long as it’s coming out of an emotion, it’s less about violence and more about why it’s happening. Is it rage, or is it insecurity, or is it a sense of loss, a sense of vengeance? You know what I mean?

Like, in season one, we could have made Fuches getting his teeth filed, like, really rough. At one point, I was like, “Oh, we should have a close-up of the file going onto his teeth and the sound of the palate going onto his teeth and his eyes start watering.” And we went through this whole thing, and then the more we talked and thought about it, I was like, “It’s kind of like when you have full-frontal nudity in a sex scene. The scene just becomes about that.” Where you’re like, “Oh my God,” instead of, “Well, what’s going on between these two people?” So, I backed away from those ideas and said, “No, what’s happening here is Barry’s watching someone he cares about being hurt. So it should be played from his point of view and he can make it stop by agreeing to a hit, which is the thing he doesn’t want to do.” Because of him caring about this guy and loving Fuches, he decides to effectively hurt himself to go on this hit. And I’m like, “Oh, that’s how we should shoot the scene. So, what are the elements we need for that?” You don’t need all the gore, and the gore will take that away.

Do you ever get notes from HBO about any of these kinds of issues, or are they pretty comfortable with what you are doing?

Yeah, for the most part. Yeah, they’re pretty amazing. Every once in a while, they might. There’s kind of that rare thing where they’re like, “Can we make this a little bit more subtle?” Which is very rare.

That’s the kind of notes you’ll get from HBO, which is like, “Can you guys just lay off this or that?” Sometimes, Alec and I get very concerned that we’re not being clear about something because we’re trying to hide stuff that pays off later. And HBO’s usually like, “No, we get it. Don’t worry about it. Just be more subtle.”

I figured they’d be pretty cool with you guys, considering that they also broadcast Game of Thrones. I feel like you’re pretty safe.

Yeah, that’s kind of our trump card, where it’s like, “Well, you guys had babies getting murdered on Game of Thrones.”

How long do you want the show to run? Do you and Alec have a sense of how much story there is to tell? Or is that still open-ended?

I mean, it’s still pretty open-ended. We talk about a number, but I’m not gonna tell you what it is. But, I mean, we talk. When we first sat down at this diner and had breakfast, and I said to Alec, “What if I played a hit man?” he went, “Ugh, that’s a terrible idea.” And then we talked about it more, and then, within five minutes, I remember him going, “Oh, hit man taking an acting class. That’s funny.” That conversation was like, “He can go from here to here to here.” And we’re the only people who know what that is. So, that’s changed a bit. It’s constantly morphing as we’re figuring him out, and we didn’t know who Sally was then, we didn’t know Cousineau or Fuches, or NoHo Hank, especially. We didn’t know any of this stuff when we first talked about this. But we kind of always thought, Oh, maybe this is a direction it’s going in. So, we’re going to kinda try to keep that. We always talk about Barry as a true-crime story you’d read about in Vanity Fair. You know those big Vanity Fair true-crime stories?

Or a podcast.

Or a podcast. Yeah, exactly.

We talk to the writers, like, pretend this actually happens. This is a thing that actually happened, and that’s the tone. How would we write it? The headline of that [story], it says “Barry,” and then it says “How a Hit Man Became an Actor,” and you haven’t seen the “and” part yet. You know what I mean? We haven’t said the full story, the full kind of headline of the series yet. It’s still getting there, if that makes sense.

But that headline might change.

Do you think Barry has the potential to actually succeed in acting?

Well, here’s the thing. He’s not very talented, but succeeding and being talented, that’s two different things. I mean, he could still succeed. But I don’t think he’s talented. So, we don’t know. I mean, that’s a big question. It’s like, “Well, he stinks.” And then we’d go, “Well, there are a lot of really famous people who stink.” In the history of acting, music, sports, everything, when you look back, you go, “Well, they weren’t really that great.” So, who knows what’ll happen with him.

But he also has the potential to accidentally not stink, like he did last season.

Yeah, I mean, every once in a while, something will click and he’s not that bad. It’s like he falls into it. It’s like as much as he keeps being pushed into killing, he accidentally will fall into a nice moment of acting.

But he wasn’t acting. I guess that’s my thing: At the end of last season he wasn’t acting when he cried and said the line from Macbeth.

True. But if I’m in the audience, I don’t know that.

Right, but can he do that again? He has to be able to do that, you know, eight nights a week if he’s on Broadway.

Right. Maybe he should just work at Lululemon. Maybe that’s the answer.

I think he should just work at Lululemon. For all of our sakes.