I used to sleep on Dragged Across Concrete director S. Craig Zahler’s couch. And sometimes his floor. We weren’t particularly close, but he and his NYU roommate had been high-school friends with my college roommate, so whenever we came to New York — which was often — we’d crash with them. This was the early 1990s, and it was through them that I learned about the Chinatown movie theaters where you could see Jet Li movies, which were not far from stores where you could buy or rent Japanese laser discs of those and other hard-to-find films. Over the years, I would occasionally hear about Zahler getting a script sold or optioned, and I had heard along the way that he’d become a Western novelist. But it was still a bit surprising when his first feature, the masterfully deranged Western Bone Tomahawk, came out in 2015; here he was finally making his feature directing debut, two decades after film school. Soon after that came Brawl in Cell Block 99, a meditative yet intensely brutal prison flick with a ready-to-explode Vince Vaughn crushing heads.

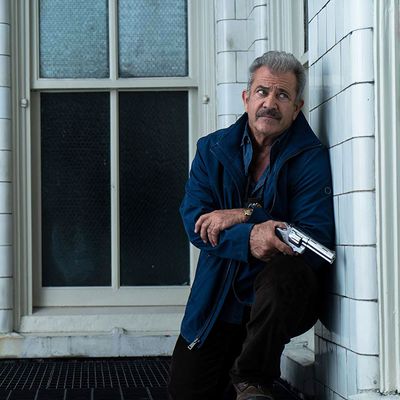

And now, Dragged Across Concrete, a nearly three-hour crime drama in which gruesome bits of violence alternate with bizarre character digressions and extended dialogue scenes. The film is partly about two cops (at least one of whom is a violent racist, played by Mel Gibson) who’ve been suspended for roughing up a drug dealer, and who decide in their financial desperation to rob a gangster. In the film’s twisted universe, the two find themselves the unlikely heroes of a heist gone wrong and a grotesque hostage standoff. In his review, David Edelstein remarked, “For all the absurdist-tragic trappings (and a cool refusal to make any one character’s point of view dominant), this is still your basic boneheaded, right-wing action movie — skewed so that its heroes’ moral relativism is meant to be a sign of their manly integrity.” Zahler claims not to be particularly political, but the film has gotten a lot of press for what some see as its veiled ideology. I talked to Zahler about his movie’s reception, casting Gibson, and how exactly he found himself with a filmmaking career so many years after film school.

I knew you years ago when you were a film student. And now here you are with three films as a director to your name. But you released your first feature, Bone Tomahawk, in 2015, when you were in your 40s. Tell me about what happened in the intervening years leading up to finally becoming a director. I recall you were studying to be a cinematographer in college.

Yeah. I shot some independent movies as a cinematographer that never got finished. I gradually learned that a well-shot movie is not so much a movie with good frosting, but a movie with frosting that is a nice color. It was kind of a two-part process for me that I’ll say began with a John Cassavetes retrospective at Anthology Film Archives, and sort of ended with Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves. I really saw that if the content is there and it’s delivered well with the performers, the movie’s gonna be good. There are some exceptions, and I would point to sci-fi and horror in particular. But I saw that no matter what I did as a cinematographer, if the script wasn’t there the movie wasn’t going to be good.

The movies I shot are mostly not things I’m proud of; it was a job, and I got the shots that I needed for my reel. Also, I was very hung up at the time with shooting film exclusively, but things were starting to go digital and I didn’t make the transition. I didn’t learn the new gear. I wasn’t shooting enough. And I got more and more interested in writing. It was something I could do, and it didn’t require anybody to give me money or to believe in me. I just had to do the hours. At this point I have eight novels and more than 50 scripts to my name. A script is a month’s worth of work, give or take a couple of days. Dragged Across Concrete was 32 days. A novel is about four to five months. I had one that took me a little over that, and then my first two novels took much, much longer — but I was also working a full-time job at the same time and playing in a death-metal band.

When you say you just started writing, which came first scripts or novels?

Actually, it started with these strange one-act plays. I had written some screenplays in college, and they weren’t good. I wasn’t really much of a writer, and it wasn’t really coming from a heartfelt place. After college, I started writing these really bizarre plays. Do you know who Richard Foreman is? I was really inspired by his work, and a little by Eugène Ionesco. Mine were these one-act plays that would play in a festival or in a night of one-act plays. Almost completely abstract. With Richard Foreman, you look at his stuff and there’s a lot of dialogue going along with these rituals, and a lot of humor, and also some pathos that you can really dig into. My favorite is Pearls for Pigs, which had David Patrick Kelly in it. I saw it multiple times, and every time I saw something slightly different in it at different points in the play. So, I was very influenced by stuff like that, and I directed some of my plays. I really believed in the magic, and I took it all very seriously.

Screenplays were the next step for me after writing and directing these one-act plays. I wanted to do something longer form. I took an idea of mine that was part of a script I had written in college, and wrote something called Incident at Sands Asylum, which had a bunch of different versions and eventually got made into something called Asylum Blackout, or if you’re in another country, The Incident, or if you’re in yet another country, Shining Night. In another country, Despair. Lots of not-so-memorable titles for that one. I poured a lot of pretty sadistic stuff and atmosphere into it. And to some extent, I was writing what I knew. It had some sanitarium stuff, and although I have not been committed, I’ve been in places like that and they were not wonderful experiences. The guys in the story are cooks and that was my job at the time, and they play in a heavy-metal band, which I also did. I think [the finished film] is an overall decent movie, but not one I love. I had a nice conversation with [horror director/producer] Tobe Hooper, who wanted to make it, but people wouldn’t get behind him, which is unfortunate. He let me know that it was one of the scariest scripts he’d ever read in his life, if not the scariest script.

You toiled for all these years, with a lot of projects that went nowhere, or got turned into something other than your vision. What gave you the confidence to keep going? How do you know when the work is good?

I’ve always been confident. And I’ve always been critical, and I apply that to myself. A lot of it parallels the development in my skills as a drummer. Now, I’ve spent many, many, many, many more hours writing than drumming, and I used to be an awful drummer. Then I got a metronome and started practicing with that, and then I started playing albums and played into click track and tried to get better and better. As a drummer I tried to hit the performances that would rival those of my favorite players in rock, jazz, and metal. I was ambitious as hell in trying to be Aynsley Dunbar or Neil Peart or one of these guys — but without the skills, which sort of yields its own thing.

So, after writing maybe six screenplays, I said, “I’m gonna write a giant fantasy novel.” This was in 2002. I’m a big fan of Clark Ashton Smith, who was an H.P. Lovecraft contemporary, as well as a lot of the pulp guys. I love George R.R. Martin, and Guy Gavriel Kay, who wrote an incredible fantasy novel called Tigana. But I didn’t want to spend forever writing it, so I thought, I’m gonna write it every day until it’s done. And, that piece wound up quite a bit larger than The Fountainhead! It was 500 consecutive days of writing without an outline. I was also working as a catering chef at the time. I had all of the characters in mind and their goals, but I figured out things as I went. That book would need a lot of revisions for me to put it out now, but there’s a lot of stuff I like about it. That was a transition point for me as a writer. Much like my early drumming performances, that book was me trying to be some conflation of Mervyn Peake and Clark Ashton Smith, H.P. Lovecraft, George R.R. Martin, and Guy Gavriel Kay, without the skills to back it up.

But do that for 500 consecutive days. I had a four-day vacation in there where I went canoeing, but other than that, legitimately 500 days without a day off. That was where I really grew as a writer. My prose got better. I became comfortable with plotting on the fly as opposed to doing an outline. I’m in this thing, this gigantic world that I’m building and discovering, every day, for about a year-and-a-half. I really figured out my process — how much I need to leave open and how much I want to plan. That fantasy novel was the writing school that I could not escape and I just couldn’t fail.

How were you able to apply what you learned on that book to writing screenplays?

The first script I chose to write after that giant fantasy book was The Brigands of Rattleborge, and that was the script that set up my career in Hollywood. I knew that my writing was at a different level at that point, and I felt very comfortable doing this sprawling Western with pages and pages of characterization, with extreme violence, with people talking about shaving cream and pies, all of the things that would fill the world because I had already done it on such a great scale with this 270,000-word fantasy novel.

I remember when The Brigands of Rattleborge was announced years ago. At various points, there were all these people attached to it. Park Chan-wook, Ridley Scott, etc. You’ve had other projects in development along the way. Is there a reason why it’s so hard to get these films made?

In my case, I think one of the reasons it’s very hard to get my movies made in Hollywood is because they are unlike movies Hollywood is making. My writing philosophies are diametrically opposed to the ones at Hollywood. For example, I probably spend the most time arguing in note calls about the idea that every scene should advance the plot. This is nonsense. Many of my favorite scenes in my books and in my movies are sequences that don’t advance the plot. I think if you’re doing compelling stuff and the characters are interesting, the audience will be interested in what they’re doing, even if it’s not advancing the plot. But if you come from the fearful place of “Oh my God, some of the audience might be bored,” then you might want to whittle that stuff out. It’s not really true when people say “the people in Hollywood are idiots,” or “the executives are stupid.” They all come from a place of wanting to make money. They’re risk-averse and want to make things more like other movies that are successful, while also maybe putting some modern, positive agenda in the mix to make everyone feel better about spending an amount of money that could save a country on a fiction — you know, give them the idea that they’re really helping the world with their superhero movie or whatever it is. They want to make sure the characters are extremely sympathetic and super likable. That means you have to have people with certain general, appealing ways and give them certain types of flaws, but certainly not the kinds of flaws that I tend to put in my characters.

So, I’m not a team player when it comes to the writing. Yes, filmmaking is collaborative, and ideally a writer would discuss things with the director, if the writer is giving it over to a director, or perhaps the actors, if they don’t understand something. To me, those are good conversations. But the conversations that you actually have are with a lot of middle-management people whose company has given you money that earns them the right to get you on the phone. They’re going to talk about how to remove all the stuff that’s potentially offensive. And my pieces are loaded with those land mines.

Speaking of land mines, was it ever a concern that Mel Gibson’s presence in [Dragged Across Concrete] might cause problems in getting it made, or sidetrack conversations about the film and prevent it from being properly appreciated?

I’m aware that that will be a discussion point for a lot of people, but the decision that I made was casting the best person for this part. You’ve seen the movie and you may or may not agree, but I cannot imagine anyone anywhere near as good for that role. And, I’d heard he was good to work with, which he was, and he was very enthusiastic about the project straight away. I’m making the movie that I think will survive and be the best version of itself, and then the conversations that people have about the private lives of the people in it — you know, I certainly wish there was more focus on the third lead, Tory Kittles, who’s been shorted by people who just wanted to talk about the hotter or more controversial issues. But my reasons for choosing [Gibson] were clearly creative, and I had a really good experience with him. Most people seem to get around it, but some people can’t, and everybody is entitled to their opinions.

But at the same time you’ve cast him as a character that will remind certain people of his past. That’s got to be on your mind at least.

I wrote that character before I ever had him in mind for the role. The cops were originally younger guys that were a little bit different. And I didn’t change it because I put him in the part. Again, I’m aware that some of this stuff will line up and will be things that people discuss. I think that will happen more in 2019 than when people revisit the movie in 2022 or whenever. But I have to stay focused on what I think is creatively the best decision. And when I put him in the role I wasn’t going to alter his dialogue so that people won’t think about his personal life. To me that’s putting the integrity of the creation, and the piece and characters, over what’s happening on Twitter, which is certainly how I look at things. I’m not on Facebook or any of that stuff.

Your work has a sobriety and patience to it that I find very compelling, and quite unorthodox — with long passages where you’re just quietly watching the characters.

Like passages in which a dude eats a sandwich for two minutes?

Yeah, exactly.

That’s what I find compelling. As much as people will speak of the graphic violence of these pictures, the idea of giving you little surprising character moments and little interactions that aren’t anticipated is key. And sometimes these scenes — like the flea-circus monologue in Bone Tomahawk, or the sandwich eating in Dragged Across Concrete, or Vince Vaughn beating up the car in Brawl in Cell Block 99 — are actually more interesting than the culmination of moments of violence. But no studio is going to look at Dragged Across Concrete and say, “That sandwich scene? You should totally leave it in.” Or, “The whole thing with Jennifer Carpenter? I’m really happy that’s in there.” That’s not going to happen. That’s the stuff that makes it more interesting to people like me, and makes the piece stand on its own. And the things that make it different from what’s been successful are not things a studio is going to be excited about, unless it’s been proven successful. Then a paradigm shift happens. Pulp Fiction comes out, and you get a million ripoffs.

But how exactly are you able to get away with such scenes without compromising?

I mean, I have to credit Dallas Sonnier. He was my manager and he put everything on the line for Bone Tomahawk. That movie we just ran and shot. We made it for $1.8 million. Most of the people involved with it had no idea the budget was that low. We had a bunch of versions that collapsed, but we consistently had Kurt Russell onboard, and Richard Jenkins almost the entire time. I wasn’t interested in making a movie that I didn’t have control over. But to get the very first one made, I would have given over some level of control because it was the starting point. In the end I didn’t have to. Dallas mortgaged his home to get that movie made. He put it financially on the line in a way that I wasn’t even quite aware of at the time. No one in the world believed we could do it for $2 million or less. Actually, no one in Hollywood believed we could do the movie for less than $10 million.

For Dragged Across Concrete, I had one apprehension about what would happen when it got to the MPAA. This is the first time that mattered. I didn’t know with Bone Tomahawk whether or not we were gonna have it rated, and it turned out we didn’t, and I don’t think that movie would have received an R rating without some cuts. But I also don’t think something like Cell Block 99 would receive an R rating. This one, I felt the movie I wrote was an R-rated movie, but there are a couple of moments that get to the very edge. So, that was something that weighed on me. Am I gonna have a bunch of discussions with the MPAA about little trims that need to be made and all of a sudden open up the picture again? I just don’t ever want to be in the position — putting in this many hours, this much time with my life — to have a creative endeavor where I blunder at the end after someone says, “No, you gotta change this.” If I had made the changes in this film that had been suggested along the way, I wouldn’t have a movie that I would be interested in. I hope that people will like the film, but I’m not going to make any creative decision because I think more people will like it.