When John Singleton burst onto the scene with Boyz n the Hood in 1991, the movie made him, at 24, the youngest Best Director nominee in Oscar history, and the first African-American to be nominated for the award. It was a momentous achievement — so momentous, in fact, that it later came to feel like a bit of a curse. Singleton made a number of excellent movies afterward, some of which earned a lot of money, but none quite matched the seismic impact of Boyz n the Hood. In that sense, he bore some similarities to the man who had previously been the youngest Best Director Oscar nominee: Orson Welles, who never lived down the notoriety of his Oscar-anointed debut, Citizen Kane.

But what about Singleton’s ambitious follow-up, Poetic Justice (1993), which many of us could argue is an even greater work, and the one that marked its director as a true visionary? Whereas Boyz n the Hood is a perfectly executed and traditionally structured coming-of-age film, Poetic Justice is narratively expansive and tonally ambling. A marvelous Janet Jackson plays a young hairdresser-poet in South-Central L.A., and an electrifying Tupac Shakur plays the loyal but volatile mailman and aspiring rapper with whom she finds herself stuck on a road trip to Oakland. The movie throws comedy and romance and tragedy at its audience, and at various points you aren’t sure which genre of film you’re watching. Passages of violence and rage are tempered by fleeting lines of poetry (written by Maya Angelou, who also has a small role); the characters might be gentle toward each other one minute, then dissolve into a hail of fuck yous the next.

There’s one moment in Poetic Justice I’ve never been able to shake, when Justice (Jackson) looks up at Lucky (Shakur) from a poem she’s writing to remark on how dirty his fingernails are. Both actors play the moment perfectly: Her remark comes from a weird stew of anger and affection and confusion, and his response is one of quiet shame, masquerading as dismissiveness. Poetic Justice is built on these contradictions. (Did you know Janet Jackson was nominated for a Razzie for this movie? Burn the Razzies down to the ground.)

There were other high points in Singleton’s career. His third feature, Higher Learning (1995), a look at a cross section of students in a fictional university where various tensions seem ready to boil over, is maybe a bit too simple in the way it divides the characters into neat, representative elements of American society, but damn, does it move. Back in 1995, its third act — in which an awkward, angry white kid (played by Michael Rapaport), who’s been seduced by neo-Nazis, starts shooting the place up — felt way too heavy-handed. These were the days before psycho racist mass shooters became a common feature of the American landscape. (In an odd coincidence, Rapaport’s character actually bears some physical resemblance to Timothy McVeigh, even though the Oklahoma City bombing wouldn’t happen until later that year.) Today, I wonder if maybe Higher Learning wasn’t heavy-handed enough. Singleton’s next film, Rosewood (1997), was an honest-to-God historical epic, about a racist mass murder in a small town in Florida, and it probably should have returned him to the Oscar fold, but it quickly vanished. A few years later, Baby Boy (2001) brought him back to the coming-of-age genre, and is even more clear-eyed and absorbing at times than Boyz n the Hood. All of these titles grow in people’s estimations with each passing year, as well they should.

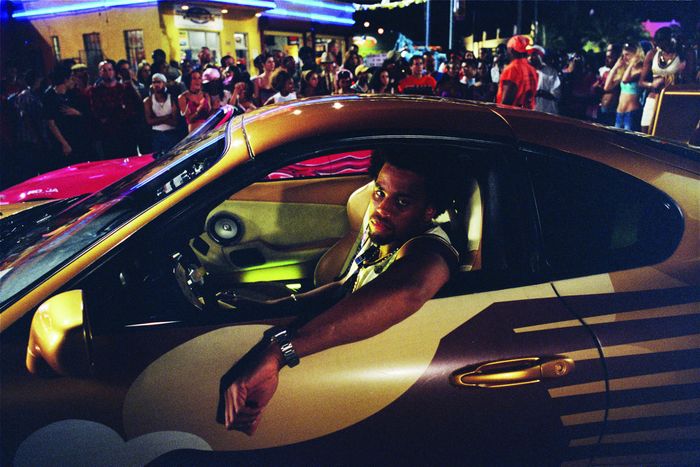

One film in Singleton’s oeuvre that people still don’t seem to have much love for, however, is 2Fast 2Furious (2003), the first sequel to The Fast and the Furious and the second entry in that series, made before Vin Diesel was brought back and the franchise reconfigured to become a cartoonish, globe-hopping, multicharacter adventure in which everybody is family. Think of this one as the road not taken for this series. On its surface, 2Fast 2Furious is a pro forma gearhead buddy thriller with Paul Walker and Tyrese Gibson as old friends from opposite sides of the law working together to bring down a drug lord. But I’ve always had a soft spot for it, in part because beneath all of its pop gloss, 2Fast 2Furious reveals something essential about Singleton’s artistry. For all its sun-drenched, candy-colored aesthetic, the film’s world is steeped in mistrust: Every character has an ax to grind. Singleton takes the aggressive, one-note conflicts of the action genre and builds whole networks of resentment out of them. This lends the picture a weird authenticity, despite the general dopiness of the plot. None of the actors feel like they’re posturing. You really are waiting for every scene to break out in violence. This is a testament both to Singleton’s vision and to his incredible facility with actors; he gets them all to commit.

In previous works, this sense of collective menace had always served a purpose: In Poetic Justice, it was the social wound Justice’s poetry would salve; in Higher Learning, the hormone-addled aggressions of the student populace served as a metaphor for an America on the edge of ruin. But here, it’s all in service of a second-rate action flick — and it actually kind of works. Against a relentlessly angry backdrop, the brief bits of tenderness between Walker’s ex-Fed Brian O’Conner and Eva Mendes’s undercover agent feel like the greatest of reprieves. Meanwhile, during the film’s big, climactic car chase, the good guys and the bad guys briefly have to collaborate to shake the Feds. At one key point, celebrating a particularly spectacular stunt, all these tough dudes who’ve spent the whole movie glowering at one another suddenly become maniacally joyous, like little kids who’ve just inadvertently launched a model rocket into outer space. It’s a weird moment — delightfully out of place in what is otherwise meant to be a macho blockbuster. The film ends with a shot of the two leads cracking the biggest smiles you’ve ever seen; the effect is that of a horrid fever finally breaking.

So maybe it wasn’t so strange that the guy who’d made Boyz n the Hood wound up directing a Fast and Furious movie. Back in college, I used to listen repeatedly to Singleton’s director commentary on the Criterion laser disc of Boyz. (That’s how big that picture was; it got a Criterion release back when almost no new releases got Criterion releases.) He wasn’t one of those chatty, nuts-and-bolts type of directors who revealed the secrets behind every scene, nor was he one of those Olympian auteurs philosophizing about the art form. But it was fun to hear someone young, coming off his first film, reflect on a work while still in that first flush of success. I enjoyed hearing Singleton engage with the characters onscreen; it was clear that these were real people for him, figures drawn from life. And maybe, ultimately, that was one of the gifts that served him well throughout his career: Whether he was making a historical epic, or a social drama, or a disposable chase flick, he wanted to make sure that the characters onscreen came alive for us, in all their messiness and rage and beauty.