On February 20, 1977, Saturday Night Live was not live from New York on Saturday night. For one thing, it aired on Sunday and at 8:30 p.m., rather than its usual late-night time slot. For another, it filmed over 1,300 miles southwest of New York. High on the success from the show’s first-season Emmy sweep, Lorne Michaels dreamed up an ambitious, near-impossible feat of television comedy: SNL would relocate to New Orleans for Mardi Gras halfway into season two for a two-hour live special.

Of course, simply approaching the orbit of Mardi Gras —a notoriously hedonistic festival complete with a parade named after Bacchus, the god of wine — is enough to lay waste to anyone’s plans. The idea of filming live comedy there on the fly is an absurd sketch premise unto itself.

Naturally, what started as an earnest attempt for America’s hottest comedy show to try something splashy quickly imploded: A drunken audience pelted the performers with coins, guest stars missed their cues, frustrated cast members threatened to walk off, and scripted bits were bungled. For better or worse, Saturday Night Live never tried anything like this again.

Vulture recently spoke to many of those involved, including Lorne Michaels, Randy Newman, Anne Beatts, and Paul Shaffer, about this anomaly in the SNL catalog, what went wrong, and how they feel about it over 40 years later.

In late January 1977, when Michaels pitched the idea of taking the show to New Orleans, NBC was understandably a little hesitant and essentially asked if anyone even knew what Mardi Gras was.

“Well, I do,” Michaels recalls telling the network executives in a recent phone interview. “Their response was something like ‘Well, they must have a better educational system in Canada.’ I had a theory, since disproven, that you could do our kind of work against real architecture — so that, in a sense, the city became the sets.”

As described in Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad’s book Saturday Night, NBC eventually relented and approved a $700,000 budget (nearly $3 million in 2019 cash) for the whole thing. Michaels had about one month to put it all together. “My reaction was ‘Oh yay. We’re going to the Mardi Gras,’” remembers writer Alan Zweibel. “I had never been to New Orleans before, so I thought, Oh wow. This is going to be cool.”

But NBC executives weren’t the only ones who needed some convincing. New Orleans native Randy Newman, whom Michaels had hired to perform on the special, had a few reservations of his own. “I told Lorne that if he thinks things are going to be organized with the city, and if he makes a deal to run a parade through somewhere, it may not go there,” Newman says. “The town is not efficient. It’s the greatest place in the world, I think. But it is not a place to get something fixed or to have a timetable that goes off on time and works.”

To be fair, Michaels’s initial plan for the Mardi Gras special seemed, if not ironclad, at least feasible. As usual, the bulk of the show would be made up of original sketches and musical performances. Meanwhile, Buck Henry and Jane Curtin would provide color commentary about the floats in the Bacchus Parade (Michaels: “That was my fallback. In case somebody didn’t make it, I could cut to the parade”). Special guests like Henry Winkler, Eric Idle, and Laverne & Shirley’s Penny Marshall and Cindy Williams would tie things together with drop-in cameos or pre-taped segments.

So at least at the outset, the blueprint for the special seemed stable, a feeling bolstered by the cooperation of the city of New Orleans itself: Mayor Moon Landrieu would even dispatch police officers to be used at SNL’s disposal upon the crew’s arrival. Plus, Michaels was already down South tackling the logistics.

“The phone company had to put in place what were called ‘telco lines’ so that we could get power for the cameras in each place that we were going to be shooting,” Michaels remembers. “So decisions on where we were going to be shooting happened before we were writing. That started the week before, when I was down there choosing locations, and that meant we had to write to those locations.”

When everyone else finally arrived to begin preparing, two weeks before the show, things were looking up — at least at first. If nothing else, the cast members were beginning to settle into and even enjoy their newfound celebrity. John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd in particular were embraced by the town, and they spent a lot of time hanging with locals in biker bars. They talked Michaels into adding a sketch that involved Harley-Davidsons solely so they could ride them through the city. Aykroyd made friends with Hunter S. Thompson, who was in town to write (the unpublished) “Fear and Loathing at Mardi Gras” for Rolling Stone.

A cast signing at the Lake Forest Plaza Mall turned into a madhouse. Fans swarmed the comedians, throwing them anything to sign from every direction, including but not limited to a toilet seat, a car door, a pair of panties, and a baby’s bottom. The public attention so overwhelmed Gilda Radner that she took to wearing a mask just to get around town.

Garrett Morris, another Louisiana native, went all out for the event, going so far as to write a song called “Walking Down Bourbon Street” to perform on the show. He even invited the entire crew to dinner at his aunt’s house the Sunday before the broadcast, according to Tom Davis, a writer for the show. “The highlight of the week,” Davis wrote in his memoir, Thirty-Nine Years of Short-Term Memory Loss, “was the party with the Morris family.” As Morris recalled in Tom Shales and James A. Miller’s Live From New York, “They had to like put their stomachs on wheelbarrows to get to their cars.”

But as the night of the special drew closer, panic began to set in behind the camera. “It was a lot different,” writer Anne Beatts recalls about the writing process in New Orleans. “It was very disorganized. I just remember spending hours trying to write and rewrite things in our hotel.”

“It was a little difficult,” adds Zweibel, “because you wanted to put on a show. You were aware of where you were, so there was a consideration for that. You wanted to make the acknowledgement of where we were, but at the same time we wanted the sketches themselves to be funny.”

It didn’t help matters that, during one rehearsal, the crew couldn’t get an accurate count of the show’s run time because cameras kept malfunctioning. And Mayor Landrieu’s promise of police protection started to fall apart: Officers became sparse as rehearsals continued, and communication with officials broke down almost entirely.

“I understood the logistical nightmare,” Michaels recalls when asked at what point the nerves started to set in. “I didn’t have my studio, I had 112 people, I had the city, and it was a big undertaking.”

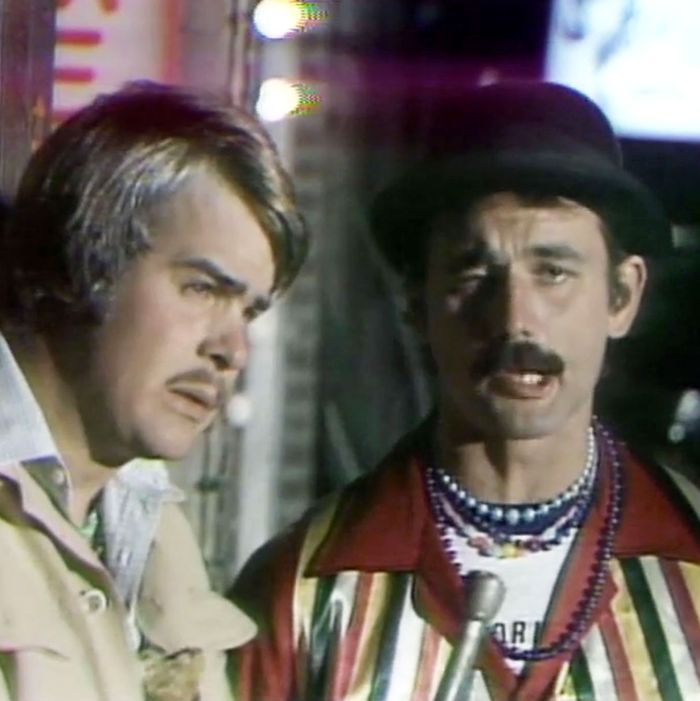

Prior to the show, Michaels and Belushi spoke to a local reporter from the New Orleans AP, further illustrating these fears. “It will be either the most humiliating night of my life or a great triumph,” Michaels said. Belushi added, “This is an experiment for ourselves. It’s ‘Let’s see if we fall on our faces.’ If it comes off, it will be a miracle.”

When the night finally came, a rowdy crowd gathered in the Mahalia Jackson Theater for the Performing Arts, right in the middle of the new Louis Armstrong Park, where they awaited musical performances by Newman, the New Leviathan Orchestra, and SNL’s house band, led by Howard Shore.

There was nothing left to do but wait.

“We were all isolated in our own little pods, really,” Newman remembers. “The rest were out in the wild.” Not that this relieved any pressure. “I remember looking at a clock after I had done a song or two and realizing that it was the same time in Chicago and we were all on everywhere. I remember I went on and I could hear my voice shaking. It was scary.”

According to local paper the South Mississippi Sun, Michaels, his face covered by a white baseball cap, took the stage shortly before the show to warm up a crowd that was already pretty loose to begin with. “Try and sit erect — you’re on television,” he advised. “Get to know the person next to you, because if we have technical problems, it might be a long wait and at least you’ll have something to say. And if you see yourself onscreen, try to act at least reasonably intelligent.” Of course, the audience dismissed that last bit entirely.

Right on cue at 8:30 p.m. Central time, the show began. The first thing viewers saw was Aykroyd, as President Jimmy Carter, addressing the nation. The camera pulled out to reveal him sitting on a statue of Andrew Jackson on horseback.

“The roar that went up as the camera panned out — I really thought everybody suddenly realized that they were stars. Right there,” says Neil Levy, who served as a production assistant on the show. “They just kind of carried themselves differently from that point on.”

The opening credits rolled with a special Mardi Gras–themed montage. Newman performed his hit “Louisiana 1927” and immediately threw to Buck Henry and Jane Curtin for their first parade-commentary segment.

Or rather, he tried.

“Everything was going well,” remembers Michaels, “and then I got a call from the mayor’s office that the Bacchus Parade was stopped because it hit a pedestrian.”

Panic set in. Zweibel and fellow writer Herb Sargent, whose prepared parade jokes were now useless, stalled as best as they could. “I was under the ‘Weekend Update’ desk, writing jokes about what the audience would have seen if the parade was in fact passing us by,” Zweibel says.

But there was no time to dwell on that. The show had to push on. A rush of Louisiana-themed sketches aired: Belushi played trumpeter Al Hirt in the Let’s Hit Al Hirt in the Mouth With a Brick Contest, a reference to when that happened to the real Hirt at a prior Mardi Gras, and that aforementioned motorcycle sketch saw Belushi, Aykroyd, and Bill Murray picking up Radner, Laraine Newman, and Penny Marshall, all dressed as southern belles.

Even as things seemed to be running smoothly, tension was building behind the scenes. Morris, so personally invested in this episode, never had the chance to perform his song “Walking Down Bourbon Street.”

“Lorne didn’t see it,” Morris recounts in Live From New York. “So now I’m not in one thing on the show, and nobody is saying anything about that. The only thing I could do is walk off, but I don’t want that reputation.” Instead, he sang a medley of Fats Domino hits in a commercial parody, but that was his only solo moment of the episode.

For a bit, things seemed fine again. Randy Newman performed “Marie,” a film by Gary Weis aired, and then the show returned to the streets, where Aykroyd, as Tom Snyder, investigated a strip club. (Fun fact: This sketch featured the first appearance of Murray’s homeless character, Honker.)

Unfortunately, the parade still hadn’t budged, so now a segment originally meant to be a fallback was in desperate need of its own plan B. “The parade is just a little delayed in getting here,” Henry announced. “Apparently, an overactive drum majorette has just had an unfortunate but interesting accident with her baton.”

With no other choice, viewers were whisked away yet again into another batch of sketches: a pretaped interview with Henry Winkler by Radner’s Baba Wawa; Belushi, playing Mussolini’s grandson, stood on a balcony at the Cabildo building, re-creating his grandfather’s 1940 New Orleans visit; Eric Idle poked fun at the (many) technical mishaps in an empty café that he swore had been rather lively just moments before.

There followed another film by Weis, a performance by the New Leviathan Orchestra, and then Marshall reporting from the Apollo Ball, a beauty pageant for drag queens. But where was Cindy Williams? As Marshall explained in Live From New York, “Cindy got lost and didn’t make the first part of it,” leaving Marshall to take over both roles.

Then, as if there weren’t enough chaos, writer Michael O’Donoghue began a repeat performance of “The Antler Dance,” an old bit he had written with Paul Shaffer and Marilyn Suzanne Miller. “I recall that Michael was not happy with the version performed on Lily [Tomlin’s episode earlier that season],” Shaffer remembers. “She was great, but perhaps the whole scene was too chaotic. He thought the chaos overpowered the lyrics and always wanted the song re-performed … So he arranged for me to fly in from Hollywood and sing the song on the show. He devised a backstory and legend to go with the song and tie it into Mardi Gras, [changing the name of the French Quarter to Antler Street], and he played the part of the masked Antler Dancer himself.”

Fitting for an event that had gone decidedly off the rails, the new version found O’Donoghue prancing around on a balcony with thousands of people hurling beads and beer cans at him.

While things continued to unravel onscreen, Radner faced a harrowing experience just after the cameras cut on her performance as the hard-of-hearing Emily Litella. “She got jumped,” Beatts remembers. “Someone tried to stick their head up her skirt.” Michaels later asked Radner about this incident: “I said, ‘What was going through your mind?’ And she said, ‘This guy is so drunk, he’s going down on Emily Litella.’”

At last, rumors swirled that the parade might finally be on its way. Henry and Curtin kept filling time, but time was running out and the crowd was growing more impatient. “Every time the lights came on the reviewing stand,” recalls Zweibel, “a gazillion drunken college kids were throwing doubloons. Buck and Jane were getting pelted with flying doubloons.” Obviously, this was something they were unprepared to deal with. “It’s not like the audience in Studio 8H starts throwing shit at you,” Zweibel continues with a laugh. “That doesn’t happen. To my knowledge, there hasn’t been a lot of vomit in the last 40 years.”

Everyone just had to hold out a little bit longer and it would all be over. Randy Newman performed “Kingfish,” and Murray shined as French pirate Jean Lafitte in the following sketch. But even here there was another hiccup.

“We got a guy to be one of the extras as a pirate,” Levy recalls, “and he had a live parrot that he came with. We told him that they were going to be shooting off these guns, and he said the parrot would be fine, it wouldn’t move. And as soon as we shot off the first gun, the parrot took off and disappeared forever.”

And the crew (finally) located Williams, who managed to make her way over to the Apollo Ball to join Marshall. Randy Newman, who had originally been scheduled to do three songs, sang “Sail Away” to close out the show at Michaels’s request. Because of this, the Meters, a local band slotted to perform, were bumped and invited back later that season.

After two hours, enough was enough. Curtin summed up the ramshackle night with one of those harried jokes Zweibel and Sargent had written under the ‘Update’ desk: “Mardi Gras is just a French word that means ‘no parade.’” With that, it was finally over.

Immediately after the special ended, Zweibel recalls, “there was a sense of ‘I’m not sure I want to ever come back here again. What do I need this in my life for?’”

Randy Newman found this to be the consensus among the cast and crew. “In all the times I did the show, I never went to any of those after-parties [at the Blues Bar]. And I wanted to go to this one … but it was much more of a wake than a party.”

If it felt like a disaster at the time, the aftermath didn’t do anything to allay those fears. When the dust settled, Michaels’s already-massive $700,000 budget had ballooned to upwards of $1 million. “I think we were beaten by a Susan Blakely movie on ABC,” he admits. “Soundly beaten, from what I remember.” What began as a chance for the series to stretch its legs ended as a fiasco.

For the cast and crew, there was no time to lick their wounds. There was just more work to do: The morning after the special, they packed their things and flew back to New York to prepare for the following Saturday’s episode, featuring Steve Martin and the Kinks, which would air only five days later.

“The ironic thing was to say that I’d been to Mardi Gras but I didn’t see any Mardi Gras while I was there,” recalls Beatts. “I saw some floats on the way to the airport the next day that were being towed away. That was it.”

As the years rolled on and Saturday Night Live evolved from underground upstart to American institution, the Mardi Gras special receded from the cultural memory, becoming just a blip on the show’s decades-long legacy. Still, the experience continues to impact, if not traumatize, some of those who were involved.

“I didn’t do Saturday Night Live again until I was promoting The Preacher’s Wife with Whitney Houston in 1996,” remembers Marshall in her memoir My Mother Was Nuts. “Why so long? I needed those 20 years to recover from what had happened in New Orleans.”

Today the special can be found only as as an extra on the series’ second-season boxed set. There are next to no clips of it online, and it’s even a bit of a mystery to NBC, who told us in an email that it’s currently located in an “offsite storage facility but there is no box number.” The episode itself, despite its mishaps and flaws, works best now as a time capsule of sorts, a snapshot of a young show drunk on its own groundbreaking success and reputation for thumbing its nose.

For what it’s worth, Michaels retains at least a few fond Mardi Gras memories. “It’s just always fun to be on location, and it just leads to a different kind of camaraderie,” he says. “Everybody’s sort of removed from their normal daily life and spending time together, so it’s really good for bonding.”

“I think it was much more of a commando cast then,” Michaels explains when asked if he’d ever do it again. “And I think also the writing was more character-driven, whereas now we’re much more topical. So the idea that we’d be doing basically a salute to a city that we all loved is harder … I thought we could pull it off, and in the end we did. But it was very hard, for sure. I think there were four people on lithium by the end of the two weeks. It was just daunting.”

“For all of us, it was just sort of seeing what our limits were,” he adds. “And we found them.”