Nicole Fosse is dancing with memories.

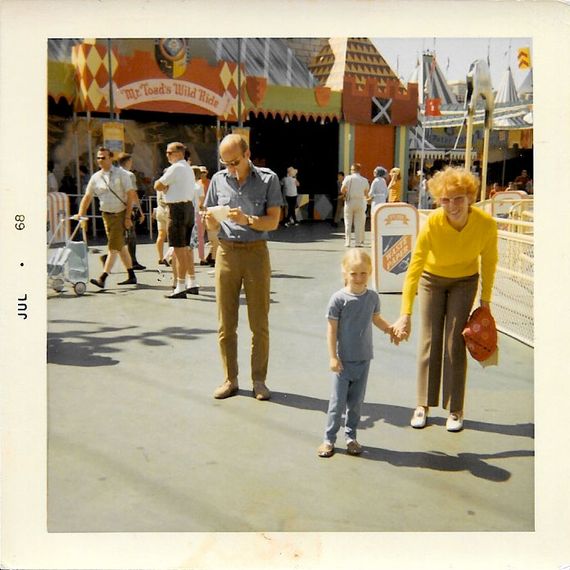

The only daughter of Bob Fosse and Gwen Verdon is sitting in a booth at Fiorello’s Restaurant on Broadway, one of the few remaining New York locations featured in All That Jazz, her father’s 1979 musical fantasy about a self-destructive, Fosse-ish choreographer-director named Joe Gideon. (A few tables over is where John Lithgow’s character, a rival director, schemed with Gideon’s producers to replace him.) Nicole is a warm, earthy, occasionally bawdy 56-year-old dancer, choreographer, actress, and producer, and an executive producer and historical adviser on Fosse/Verdon, the FX series about her parents, played by Sam Rockwell and Michelle Williams. She has traveled from her home in Woodstock, Vermont, to talk about a scene of intense personal significance: a dance number, in the eighth and final episode, between her father and her own teenage avatar.

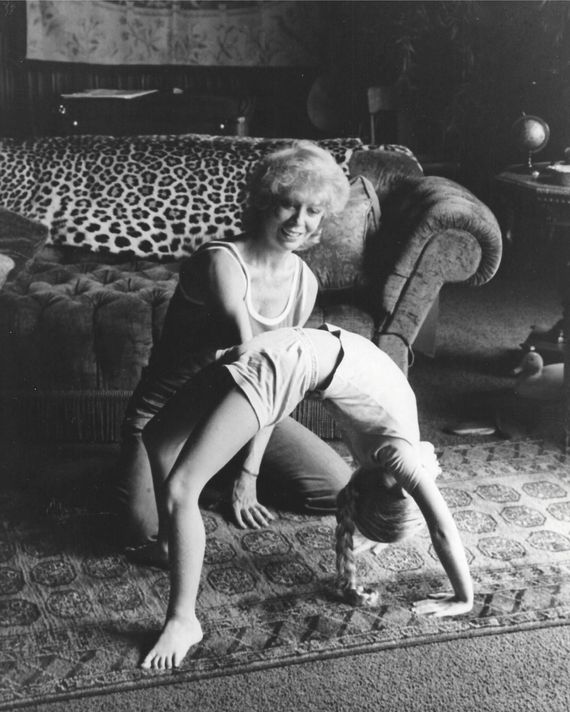

Nicole choreographed the number with a disarming naturalism that belies its layers. The dance takes place in the living room of then 52-year-old Bob’s New York apartment, where 16-year-old Nicole (played by Juliet Brett) is living, seven years after her parents’ separation. The scene is suffused with a father-daughter affection that might not make sense to people outside the dance world, but as Bob holds Nicole like a guitar and shows her how to move her arms and legs, a secondary, familial tension underlines the routine. Bob is an awful role model who historically ditched Nicole, is absent when it matters most, and brings home disposable women not much older than her. At this point in the story, Nicole is depressed and acting out in ways that foreshadow her real-life struggles with relationships, alcohol, and drugs. But for a fleeting few minutes, they’re partners in a hint of the artistic bond that her father still shares with her mother even after he’s destroyed their marriage.

“I always danced with my father in the living room,” Nicole says. “He did lifts with me, and he would twirl me around, and we’d laugh and giggle. He’d [direct] me like he would a dancer’s body, like, ‘Put your leg over here. Do this, do that.’ Then one day, he asked me to stand behind him and do the ballet version of what he was doing.” That living-room dance, decades before getting depicted in Fosse/Verdon, became the inspiration for the “Mr. Bojangles” number in Bob’s 1978 revue Dancin’. “In the series, it happens after he’s already done Dancin’, but that’s a bit of theater history that almost nobody else would know,” she adds.

The scene has a meta-dimension as well as a historical one: All That Jazz contains a similar scene where Gideon (played by Roy Scheider) and his 12-year-old ballet-dancer daughter (Erzsebet Foldi) practice while she interrogates him about his love life. In the movie, Gideon realizes he’s late for another engagement and cuts the questioning short, carrying her downstairs with her legs locked around his midsection like a single handcuff. The father-daughter number on Fosse/Verdon mirrors some of the movements and lines from All That Jazz, but the feeling is different. This dance creates a moment of détente and mutual respect in a relationship that’s otherwise awkward and distrustful.

Fosse/Verdon is filled with scenes like this, which allude to and critically annotate Fosse and Verdon’s art. Like their stage productions and Fosse’s films, it’s an often-nonlinear tale that jumps between past and present, memory and fantasy, psychodrama and inside-showbiz potboiler, straight drama and musical. It even lifts lines and images from films and musical productions that Fosse and Verdon worked on, putting them in different contexts that shed fresh light on where they came from and the motives of people who used them first.

“I had this conversation with one of the [production assistants] on set about a scene that’s kind of like a scene in All That Jazz.” Nicole says. “Nicole is sitting with Bob and he takes some Dexedrine and she says to Bob, ‘Can I have one?’ and he says, ‘No, it’s candy. You can’t have one.’ She says, ‘Well, if it’s candy, how come I can’t have one?’” In All that Jazz, the moment is a mordant but charming throwaway, reaffirming that even though this isn’t the sort of thing a child should be privy to, at least the father and mother (played by Leland Palmer) are doing what they can to preserve the girl’s veneer of innocence.

There’s no such delusion in Fosse/Verdon. The child matures against a panorama of dedication and genius, but also infidelity, substance abuse, professional treachery, and unthinking callousness between entertainers who might also be friends, lovers, or spouses. Bob seems largely oblivious to the toll it’s taken on Nicole, while Gwen seems either too wrapped up in her own personal and career problems to properly monitor the situation, or else sadly apologetic about her inability to change things. “Shooting the pill scene, the PA on set asked me, ‘How does it feel when you watch that?’ And I said, ‘Well, I have two brains. I have my child brain that does not notice that that is odd behavior. And then I have my more newly formed ‘recovered’ brain that says, ‘Oh, there’s a father doing drugs in front of his child.’”

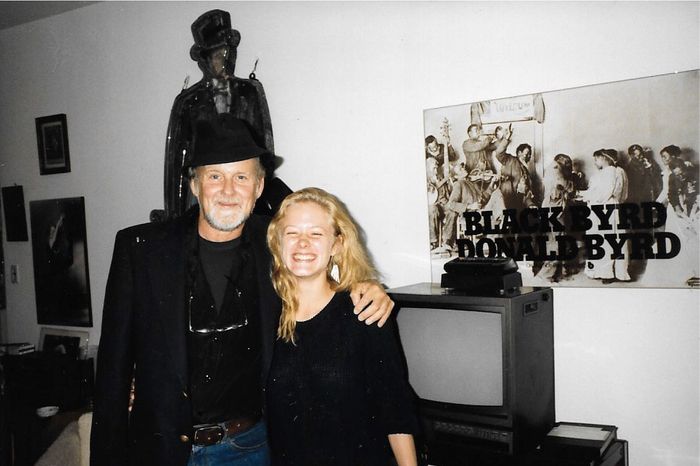

Thirty-two years after her father’s death and 19 years after her mother’s, Nicole Fosse is an entertainment-industry veteran and single mom of three now-adult sons, living far from Broadway. She has a different take today than when she was a child and a young woman, living in the middle of it, in an era when behavior we think of as destructive was considered an occupational hazard. “As an adult,” Nicole says, “and even more so, working on this show, and watching situations and characters from my own experience come to life as drama, it’s become clear to me that I’ve changed my point of view about a lot of stuff I used to normalize.” The experience helped her understand how so many people in her father’s life put up with his toxic behavior, and why she unknowingly emulated it as an adult, doing drugs and falling into destructive relationships.

“There are times when Bob will act like a jerk in this, but I find him so charming that I get sucked into thinking, ‘Well, maybe he didn’t really mean it,” even though I knew him about as well as anybody, you know? And then the mature woman part of me steps in and says, ‘No, that’s not okay. That’s hurtful and harmful.’”

Fosse/Verdon came about when the series’ executive producer, Thomas Kail, director of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical In the Heights, called Nicole and suggested doing a series about her father based on a 2013 biography by Sam Wasson. Then Kail and Steven Levenson, co-producer of the FX series as well as the Broadway hit Dear Evan Hansen, drove to Fosse’s house in Vermont, rented rooms at the Hanover Inn, and spent the weekend going through her “own personal archival material that’s not accessible anyplace else except through me.” After that, she says, “The project changed direction and became more inclusive of Gwen Verdon, and also of my perspective, which is not included in the Wasson book, which I didn’t participate in.”

Nicole Fosse oversees her family history, administers staging rights to her father and mother’s work through Fosse/Verdon Legacy LLC, and hosts events celebrating their work. But she’s mostly stayed away from biographies of Bob Fosse and theater histories that mention her family. Friends and family read things on her behalf, then advise her to check out particular sections if they think it’s worth knowing. She doesn’t generally contact authors, and she rarely does interviews because “I don’t want my own life to be solely about preserving my parents’ lives.”

She changed her mind and decided to take an active role in Fosse/Verdon for two reasons. First, “the written word can be interpreted different ways, but as soon as you put something on film, you are memorializing a certain version of events in a way that’s visually much more concrete.” She wanted to participate in sculpting that version. Second, and most important, she wanted to be sure that her mother’s story was given equal weight. There had already been multiple accounts of her father’s life — plus a cinematic autobiography — but nothing on Gwen Verdon. “And as wonderful as Wasson’s book was, it was really incomplete, because it did not really include my mother. As of this moment, there’s not even a biography of her.”

That, plus the relative dearth of video footage compared to the Bob Fosse treasure trove, meant that Michelle Williams would turn to Nicole for help with fine brushwork. “Michelle and I talked for hours and hours and hours about my mother’s personality and how she would respond and react,” Nicole says. She would share distinctive things that her mother said, and the actress would add it to a mental database of phrases she’d gleaned from listening to recordings of Verdon.

Nicole helped Rockwell, too, although the situation was less daunting because of the amount of Bob Fosse–related material already out there: “He studied my father’s hand gestures and facial expressions. He went to a dialect coach, and he listened to interviews of my father speaking on set all the time. He’d have my father’s voice on an iPod playing in one ear, then he’d take it out, do a scene, and whenever he had a break, the iPod would come out again.”

She says that it took a while for her to get used to the idea of somebody other than Roy Scheider playing her father, but she grew to appreciate the qualities Rockwell conveyed that the public had never seen. “There were times when I looked at Sam in makeup and it felt like it was my father sitting there. He has a way of becoming very introverted at times, lost in his own thoughts, that is to me reminiscent.”

The production design, set decoration, and costumes turned the experience into even more of a memory trip. “My first day on set was when they were filming a party in our living room. That set was exactly my living room. There were cherubs on the wall, and paintings of mothers and babies and orange crushed-velvet wallpaper, and a white marble fireplace and these wrought-iron things, and a psychedelic couch.”

The writers and co-executive producers—including Lin-Manuel Miranda, who has a cameo in the finale as Scheider, and Joel Fields of The Americans — were all concerned with the minutiae. They had a policy of confining the story to things that were on record as having definitely happened, or that plausibly could have happened, based on what they knew about Fosse, Verdon, and the constellation of famous names orbiting them. (The show’s supporting cast includes Margaret Qualley as Fosse’s young dancer girlfriend Ann Reinking, Norbert Leo Butz as his best friend, Paddy Chayefsky, and Nate Corddry and Aya Cash as Neil and Joan Simon.)

Speculative moments included the lobster race at Bob’s house in Quogue (inspired by Nicole watching her father bet crab races in Acapulco), the bit where the Pippin dancer knees Bob in the groin to end his unwanted advances, and the scene where Gwen starts hurling and breaking things to express fury at her husband. The dreams and fantasies are taken from what the writers learned about Fosse and Verdon’s psychology by consulting archival material, preexisting biographies, and, of course, Nicole’s own memories. “Stuff like that all falls under the heading of, ‘We don’t know that it happened, but we also don’t know that it didn’t happen,” she says. “Like that one fit of rage of my mother’s. It falls within the spectrum of possibilities, because we know that she once threw a TV set out of a window because she was so upset with something a reporter said.”

Even with a general commitment to accuracy, there were compressions and omissions. Gwen’s devoted boyfriend, Ron (played by Jake Lacy), is a composite mainly based on actor Jerry Lanning. “Even if you’re trying to stick to the facts, the obligation to make every part of the series work as an episode of television means that you’re going to have to change some things,” Nicole says. “I hope most of the changes we made are permissible, like in good historical fiction.”

In the end, Nicole says working on the series helped her to compartmentalize conflicted feelings about her father, though she’s still figuring out how exposure to her parents’ troubles might have shaped the drama of her own life, which included a hard-partying stretch in her teens and 20s (the beginnings of which are alluded to on the show) and a tendency to get involved in crash-and-burn relationships. “It gave my mother a hard time, seeing me go through all that, but I was just copying what I grew with,” she says. She mentions a particularly bad relationship in which she was filtering out the destructive parts by “doing a really good job of ignoring the negatives and focusing on the positives.” She finally got out of it when she realized the negatives weren’t going away. That experience echoes comments her mother made in a 1980s interview about why she separated from Bob. As Nicole recounts: “She said she needed to be with a man she admired. She told the reporter that she wanted to extricate herself from parts of Bob that she no longer admired, but stay involved with the other parts.”

Another bond that Nicole shared with her mother is the trauma of losing a husband. Gwen Verdon watched her husband die on the sidewalk in Washington, D.C., in 1987, after suffering a heart attack on the way to attend the opening night of a Sweet Charity revival. In 2000, Nicole’s husband, stagehand Andreas Greiner, whom she met during a tour of West Side Story, was killed by a drunk driver, leaving her alone with three children. Gwen quickly moved in to help her, only to die eight weeks later.

“I think she died of a broken heart,” she says. “I know how that sounds, but how else can you explain it? She was an absolute nervous wreck, and trying not to be, showing up for me and three little boys aged 1 and a half, 3, and 8.” Losing her husband and mother so close together shocked her into getting “totally sober,” because she realized the burden of caring for her sons was entirely on her, and she no longer had the two people most likely to pick her up if she fell. “What if you get everybody off to school, then take a hit off a joint, and the school nurse calls you to tell you that one of your kids broke an arm? Not to throw shade on myself, but that was the reality I was facing, and I had to do something.”

The more deeply Nicole Fosse delves into her own story, the more it sounds like a dark musical fantasy-drama of the type that her parents used to make, though with an uncharacteristic streak of optimism, and what could pass for a happy ending if you squint a bit. When she describes the versions of herself that are represented in Fosse/Verdon, she counts seven: “There’s an infant me, there’s a 7-year-old me, there’s a 12-year-old me, there’s Erzsebet Foldi me, there’s a teenaged me, there’s a 40-year-old me, and then there’s me.”

But she doesn’t believe any of those stages can be separated from the rest, because “even when you’re 75, the 5-year-old you is still present. I don’t know where the present ends and the past begins. It’s a little bit like what my father said in All That Jazz: I don’t know where the fantasy ends and the reality begins. Or maybe it’s the other way around, I don’t know. Does it matter? I’m a Fosse.”