For an episode titled “The One Where the Sun Comes Out,” here are two relevant sayings for this extremely lively and fretful hour:

• Sunlight is the best disinfectant.

• It’s always darkest before the dawn.

Much like its predecessor, The Good Wife — and a show like ER, for that matter — The Good Fight takes place in Chicago but doesn’t work terribly hard to convince viewers that it’s actually shot in the city. The sunny-morning montage toward the end of the episode is generic B-roll footage—the Hancock Center, the Wrigley Building, Buckingham Fountain, and so on, almost certainly the handiwork of another production. But give the show credit for this insight in my home base: The bizarre mid-May hailstorm that underscores the drama is entirely plausible, part of a broad array of precipitation options that confuse and terrorize residents for eight or nine months out of the year. (Lousy Smarch weather!)

The thunderclaps and ice balls that crash outside Reddick, Boseman & Lockhart for much of “The One Where the Sun Comes Out” emphasize a grand reckoning that shakes the firm’s foundations. The Good Fight is a show about the difficulties noble-minded people have in living up to their ideals, and it’s absolutely merciless about exposing their flaws, even as it’s sympathetic enough to put them in context. It’s easy to make the morally correct decision when nothing important is on the line, but when careers and the business itself are at stake, doing the right thing can have devastating consequences. And seemingly everyone in this episode is forced to choose between bad options.

The initial prompt for all this soul-searching is an internal investigation ordered by Chumhum, Reddick-Boseman’s biggest client, which makes its continued patronage contingent on a thorough review of the firm’s culture. For that, they bring in Brenda Decarlo, a lawyer who specializes in issues of sexual impropriety and demands unrestricted access to the entire staff. Decarlo is played by Cheryl Hines, who most will recognize as Larry David’s exasperated wife on Curb Your Enthusiasm, and she puts plenty of comic spin on the ball. Decarlo has pseudobulbar affect, a condition that prompts sudden jags of laughing or crying, though the writers exploit it at such maximally awkward and unnerving moments that it doesn’t seem quite so spontaneous. (When Decarlo catches on to the fact that Liz and Adrian perjured themselves about their sexual encounter, she punctuates their dismay with a sinister-sounding giggle.)

In the bigger picture, Decarlo’s investigation uncovers the massive dysfunction that’s been roiling the firm all season, especially the racial discord that the partners tried to buy their way out of addressing. She notes that the associates are segregated into different pockets of the office — which is also very Chicago, though the show doesn’t note it — and isn’t satisfied by the defense that the firm’s “hot desk” policy, which allows employees to pick their spot, absolves them of responsibility. There’s also a complaint about cultural appropriation, another about women getting all the choice promotions to the matrimonial division and elsewhere, and still more about black mail-room workers who are expected to show solidarity with black associates in such disputes, but get no support of their own because they have no power. Marissa again has occasion to get defensive about her racial attitudes and the whole bull pen dissolves into a shouting match.

Yet the issues don’t end in the bull pen. Earlier in the season, Liz had quietly asked Marissa to look into other women her father had sexually abused, in what was a sincere attempt to square up to the full extent of her father’s sins. But the ominous folder containing Marissa’s report suddenly becomes a toxic asset, all the proof Chumhum needs to distance itself from a firm that hasn’t been living up to its ideal. When one of the founders of the business, a civil-rights hero, is revealed to be a sexual predator, it’s hard to build out from such institutional rot. Liz’s answer to this moral dilemma is to shred the documents and swear Marissa to secrecy, which is devastating to Marissa, who assumed her boss was working toward a higher standard.

More devastating still to Marissa is her betrayal at the hands of Maia, who seems to complete her season-long heel turn, though it’s much more ambiguous than it looks. Fired from the firm and logging hours at a dumpy consult-a-lawyer operation, Maia takes an opportunity from her old nemesis, Roland Blum, to build a new firm from the ground up. Blum is responsible for Maia’s termination, but he’s also the type of monster Maia understands because she has some of those killer instincts, too. She’s not that far removed from her Bernie Madoff–like father — and, in fact, she’s happy to turn that association into a sales pitch when a potential client expresses his admiration for the swindler. But Reddick-Boseman’s attempt to get Blum disbarred for having his dietitian pose as an insurance rep summons Maia’s survival instincts, even if her closest friend is collateral damage.

The night out between Maia and Marissa is exceptionally well-written and performed, and pays off all the hard work the show has done to solve its Rose Leslie problem. Maia arranges this seemingly casual meet-up to work Marissa for information, following up on Blum’s assertion that Reddick-Boseman is hiding damaging information about Carl Reddick’s behavior. It’s Blum’s only leverage against the firm, and therefore Maia’s only move, too, if she wants to salvage her career. Rose plays the scene perfectly: She has successfully manipulated Marissa into giving up the details she needs, but she still feels genuine remorse about the wrecking ball that she’s taking to her friend’s life. Maia has become a cutthroat under Blum’s tutelage — or maybe Blum’s presence has merely brought out the cutthroat who was always there — but she’s not without feeling.

In the end, though, nothing matters. The sun comes out the next morning and none of these terrible actions influences the outcome. Liz and the partners didn’t have to work so hard to cover up or minimize their sins because Decarlo is more or less satisfied with the state of the firm. Its current dysfunction, in her estimation, is mostly a consequence of rapid growth. Maia getting the dirt on Carl Reddick doesn’t matter, either, because it doesn’t save Blum from a recommendation of disbarment. Characters like Liz and Maia have compromised themselves to no benefit. And for Marissa, who’s still young and idealistic despite being Eli Gold’s pessimistic daughter, these revelations shake her to her core.

Hearsay

• Like many viewers, I was perplexed that last week’s Jonathan Coulton animated explainer was replaced by a title card claiming it was censored by CBS. And like many viewers, I dismissed it as a subversive little joke on the show’s part. But Emily Nussbaum of The New Yorker details a genuine behind-the-scenes dustup between CBS and the show’s producers, Robert and Michelle King, who threatened to walk after the network killed the song, called “Banned in China,” over concern that it would upset the notoriously censorious Chinese government. The title card was a compromise solution to denote the King’s displeasure over what happened to the short.

• Diane’s break with her “Book Club” ends her experiment in fighting fire with fire to beat Donald Trump in 2020. The group’s tactics have been mirroring its adversaries — pumping out fake news, hacking voting machines, etc. — and all under some dubious moral relativism. Her “Book Club” extremists think it’s okay to subject Michael Tyrek, the man responsible for the family-separation policy at the border, to a “swatting” because his sins merit a proportional response. His death doesn’t slow the group down at all, nor does Diane’s revelation that its founder, Valerie, is actually a con artist who’s currently doing time at Rikers. They’re way past Valerie now, and their new threat to Diane is real.

• Nineteen minutes before the opening credits this week. That’s how you know it’s going to be a lively one.

• Quality spit take from Michael Boatman as Julius when Decarlo suggests he’s been sleeping with Marissa on the side. That’s an old-fashioned comedy go-to that deserves a revival.

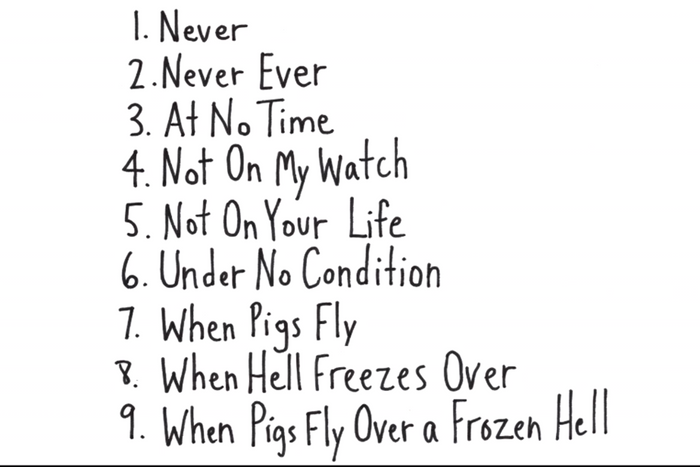

• From Coulton’s delightful closing-credits number of cultural appropriation, here’s that list of times when blackface is acceptable: