Much like the story of the doomed Greek Titan and fire thief named in its subtitle, English novelist Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus is a cautionary tale about the dark side of ambition. The mad Dr. Frankenstein’s grisly experiment in replicating the gift of human life brings him pain, failure, and death. Prometheus’s reward for granting humanity the gift of fire was exquisite torment and the grief of knowing his blessing led to a great deal of warring and suffering. You can get what you want if you try, to paraphrase the Rolling Stones, but you’re in for a mess if you haven’t considered the consequences.

Odd Future’s game plan at the top of the decade seemed to be to topple the existing idols and stomp on the broken pieces. If you made it into a room to see the collective perform live in the year it released Earl, Rolling Papers, Bastard, and BlackenedWhite, you were treated to a carnival of youth rage whose point, if you could see past the veneer of chaos and gore, was that the way we run things is wrong, and there’ll be hell to pay if we don’t change course. The kids were all right; we’re closing the decade in more mess than we started it in. What they didn’t see coming is what happens after you incite a revolution. Eventually, iconoclasts have to learn how to be icons and work harder than their predecessors, or be brought low by a new generation of feisty youths like themselves. It’s poetic: Be better or be broken.

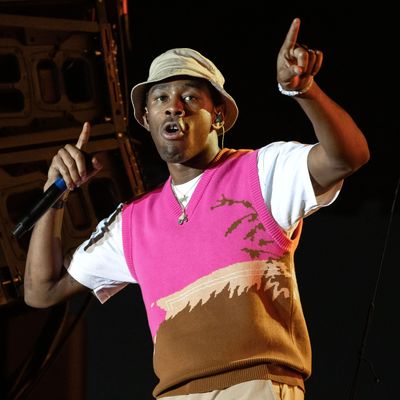

Tyler, the Creator has been working on himself, from the ironic psychiatrist’s couch breakdown of 2011’s Goblin through the crude but occasionally sobering deep thoughts of 2013’s Wolf, the abrasive venting and late-night longing of 2015’s Cherry Bomb, and 2017’s Flower Boy’s late-stage revelations. A sound that began as a study in contrasting grotesqueries buffed away the rust and divots. What came off three albums ago as studious Pharrell and Kanye fan service from an auteur still picking up chops as a songwriter has blossomed into a robust artistic vision worthy of its heroes’ participation. But the question of what to do with that voice — a low ramble reverberating from the depth of what seems possible for a human, warped at times to sound even more devilish, so that when it dressed you down, it sounded like words from Baphomet — lingered.

Flower Boy planted softer voices around all Tyler; like the bed of sunflowers on the cover, it made the marquee artist seem like less of a forbidding figure. The raps kept the record rooted in the lineage of its forebears, but the subject matter couldn’t be further removed from the era when the message was “Kill people, burn shit, fuck school.” At live shows in the wake of the album’s release, it was easy to surmise where Tyler’s interests were taking him. He seemed to have the most fun leading the crowd in sing-alongs, not rattling off the tongue-twisting lines that used to be his main focus. The soulful “911 / Mr. Lonely” was a gauzy outlier on the Flower Boy album, but two years later, it’s looking like the shape of things to come.

IGOR, album No. 5, doesn’t share Flower Boy’s interest in bracing Tyler’s day-one fans for change. Tyler raps when he feels like it now, sometimes not at all. If you came to hear witty two- or three-verse rap hits, you might want to march to DJ Khaled’s latest, Father of Asahd, instead. IGOR centers emotions and musicality, focusing primarily on skills as a writer of love songs that Tyler accrued across back-catalogue gems like “She,” “Awkward,” “Analog 2,” “Fucking Young / Perfect,” and “See You Again.” IGOR’s still packed with guests giving pretty, understated, and uncredited vocal performances, but Tyler’s center stage singing with them this time, albeit through quirky filters. He used to pitch his voice down deep to increase the menace, but he’s running it way up high now. Where it used to conjure demons, it now evokes cherubs and children.

Softening his voice allows Tyler, the Creator to deliver the kinds of jazzy melodies he’s been playing at all along, this time without a buffer of a proxy, which opens up space for the lyrics to get a little more direct. Hearing singers trade lines on Flower Boy gave some listeners room to suggest that the songs were all written for characters, which helped them to sidestep the latent queer messaging peppering the album. There’s no equivocating the meaning of IGOR’s “New Magic Wand,” though, a song about nudging other people out of the frame to get closer to a crush; or “A Boy Is a Gun,” a chronicle of a breakup with a guy who’s a bad match; or “Puppet,” a freak-out about sacrificing autonomy to make a relationship work. IGOR is the bookend to the sugar rush of Flower Boy. It details the loving, arguing, making up, and breaking up that happens after a crush jumps out of your dreams and into your car.

(This mid-album trilogy contains some of the most refreshing verses about same-sex attraction in a major label hip-hop field of play since Frank Ocean switched pronouns on the love interests he was singing to, and Kevin Abstract, Young M.A, and iLoveMakonnen spoke their truths. It seems late in the game for these kinds of songs to carry a bit of shock, for the pastel Grace Jones vapors in the album art to feel empowering, for the worry of how it’ll all be received by the public to settle in afterward. We should’ve had LGBTQ hip-hop artists flourishing on majors, headlining festivals, hosting radio shows, and giving great interviews all along, but we’ll take what we can get, and continue taking and getting what is deserved.)

IGOR’s more than just a love album. Tyler’s still navigating a world of naysayers and notoriety, and some of those concerns bleed through, particularly on the obligatory rap workout “What’s Good,” where he flexes on his designer tastes and meditates on mortality, revisiting an incident from last fall where he pushed himself too hard in the studio, fell asleep at the wheel of his Tesla Model X on the way home, and crashed into a parked car hard enough to push it 50 feet away. There’s darkness in IGOR’s margins, in the eerie drowning metaphor of “Running Out of Time,” but it never eclipses a feeling of giddiness and yearning. This is thanks to the arrangements, where Tyler’s wide-ranging interests in jazz, rap, soul, and electronic music meld into lush, winding suites.

My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is an obvious point of interest, not only for its creative use of outside guests but also for the artful, proggy structuring. The heady love suites of Marvin Gaye’s I Want You and Leon Ware’s Musical Massage are inspirations as well. (“I Think” name-checks both Ware and the Marvin album he wrote and produced.) IGOR drifts where Tyler, the Creator albums used to whip, zip, and crash. Listening to the drippy choruses and instrumental passages comprising songs like “Earfquake” feels like catching the trail of an enticing perfume or cologne on the street and meeting a potential soul mate at the end of it. In the hands of a lesser talent, these songs might seem aimless, but as is the case with Solange’s When I Get Home, the sequence feels like a journey. Even the fragments have purpose.

It looks like the artist has been priming us for this moment for years, bulldozing the runway and carefully crafting the plane before he took flight. Each album’s advances were necessary to get to this. Tyler, the Creator is appreciated as a trickster who loves curveballs, but looking back over the last ten years’ worth of sharp turns and unexpected revelations, you wonder if there was a plan all along. This album is so pretty, confident, and considered that you wonder why he named it IGOR. Tyler, the Creator’s not a freak or a goblin or a monster anymore.

*A version of this article appears in the May 27, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!