When the Tupac Shakur hologram graced the 2012 Coachella music festival with its glowing, eerie presence for a couple of numbers with a flesh-and-blood Snoop Dogg, it was unsettling enough. One year later, when Ari Folman unveiled his live-action–animation hybrid The Congress, a loose adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s cult sci-fi novel that imagined an actress signing over her physical form to the industry, the film heralded the vanguard of an existential apocalypse.

In the early 2010s, personhood itself seemed to be coming to an end as fanciful new equipment enabled the complete capturing, digitization, and control of a real figure’s digital likeness. Whether it was ’Pac rising from the dead to sell tickets or Robin Wright fictitiously selling her image to the studios, new advances accelerated the erosion of the self for the sake of dark financial imperatives. These hinted at a slippery-slope future that has now come to pass in our real world, as the likes of Peter Cushing and Carrie Fisher get digitally exhumed from their graves, propped up and marched around to give the latest Star Wars a little extra something-something. Even with all the everyday surreality that sounds like a prepackaged Black Mirror episode, I’m still surprised it’s taken Charlie Brooker five seasons to get around to this one.

“Rachel, Jack and Ashley Too” concerns itself with the splintering and displacement of consciousness, specifically that of pop star Ashley O (Miley Cyrus, vivisecting her erstwhile Hannah Montana persona). The micromanaged ingénue works a “Natalie Portman in Vox Lux” vibe with an added dash of teenybopper appeal; lavender wig, rapidly deteriorating mental state, pseudo-inspirational messaging about being able to do anything if you just believe in yourself. Ashley’s mom died, her aunt Catherine (Susan Pourfar) and the Eugene Landy knockoff with whom she’s in cahoots keep pushing aggressive feel-good medication, and several intimidating deadlines for recording and touring loom on the horizon. Ashley’s feeling stressed, and the rollout of a foot-tall robot imbued with a facsimile of her mind named Ashley Too isn’t helping.

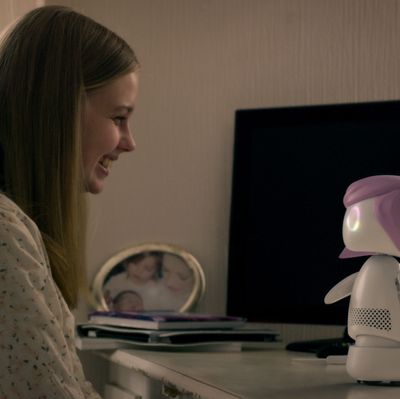

Brooker takes a two-front approach to this story, splitting his first act and a half between Ashley and one of her more devout fans, Rachel Goggins (Angourie Rice). She’s got another dead mom, a dad doing his best while working the kinks out of his humane mouse-taser, and a septum-pierced older sister, Jack (Madison Davenport), who’s impervious to the ministrations of bubblegum music. Mimicking Ashley’s hairstyle, catchphrases, and dance moves for a school talent show, Rachel’s as much of an extension of her idol’s self as the shiny, happy Ashley Too she receives as a gift. Lonely kids without much going on make up the pop-industrial complex’s bread and butter, and Rachel fully buys into the pap peddled by the executive team trying to pull Ashley’s strings.

Brooker situates the nefarious machinery of pop music on one side of his narrative and its psychological casualties on the other, though his critique never gets past the passé notion that Top 40 tracks possess zero artistic merit. He draws a tired dichotomy between the supposed creative bankruptcy of pop and the false legitimacy of “real” rock and roll, crystallizing the divide with the contrast between an idiotic parody of “Head Like a Hole” titled “Hey I’m a Hoe” and the concluding performance of Nine Inch Nails’ genuine article. At least the episode finds some humor in how far over the top it can push this rockist tendency, exposing a sinister Svengali using pills to keep radio hits stupid and profitable. She’s Ashley O, we’re informed, not “Leonard fucking Cohen.”

Of course, it would be the record label’s wildest dream to scrub the human element from its talent, leaving only an obedient collection of pixels. That perversion of identity gives the episode a structural spine, and the same basic concept joins Ashley’s plotline with Rachel’s in a clean dovetail. Nasty aunt Catherine wants to medically induce a coma so that songs can be plucked directly from Ashley’s dormant brain (through a patently absurd process in which a scientist plucks A’s and G-sharps from a computerized ether like he’s playing Minesweeper) until the brand-spanking-new hologram gets off the ground. Meanwhile, Rachel’s Ashley Too shakes off the firewall restrictions limiting the android to 5 percent of its mental capacity, in effect transforming into a tiny duplicate. Ashley Too can sense Ashley One’s peril, sending one narrative strand careening into the other behind the wheel of a novelty mouse-mobile.

Brooker’s ginned up a sound concept, so long as his musical politics don’t rub you the wrong way (and I’ve got nothing against a healthy distrust of industry plants), and yet his execution lacks the cleverness and finesse that came standard with early seasons of Black Mirror. Poor dialogue dumbs down each piece of a potentially intriguing story; why, when Ashley Too shakes off her tech-yoke to become her full self, does the pint-size gizmo speak predominantly in F-bombs?

The presumptive answer lies somewhere between “because hearing a little robot curse is funny” and “because hearing Hannah Montana curse is funny,” neither option passing muster onscreen. Likewise, when Ashley climactically storms the hologram-unveiling event to expose her aunt’s treachery, she can’t summon anything more cutting than a middle finger. The villain also seems to be at a loss for words, settling on “Aw, fuck it” instead of, say, anything else. This series prides itself on parting with reality without losing hold of realism, but not even the surly-big-sis dialogue scans. We know this isn’t the best Brooker’s got.

Like “Smithereens,” this episode stops rather than ends, filling itself out with a de-pop-ified rendition of “Head Like a Hole” that Ashley claims to have written. A dethroned chart princess filling the cultural vacuum left by Nine Inch Nails sounds like a far richer speculative premise than “What if the Tupac hologram concealed a festering hotbed of corruption and predation?” Brooker, however, doesn’t fully explore either of them with the diligence he brought to “The National Anthem,” to name one example. There was a time when the show would have wondered to what extent the label has legal claim to “Ashley O,” which ontological aspects of her being truly belong to her, et cetera.

Instead, we’re left with a corny music video likely included to help persuade Cyrus to sign on the dotted line. An outside observer can see what would’ve drawn her to this gig: all the faux music videos could be shot on a soundstage over an afternoon, the CGI of Ashley Too simplifies Cyrus’s performance to the point of being half-dubbed-in audio, and most important, she gets to subvert her best-known role. Still, however the script may pick apart the specter of Hannah Montana with the less-than-daring suggestions that fame imprisons the famous and that starlets hold a lot of pain behind their squeaky clean exteriors, it leaves the deconstruction underdone. The final scenes merely gesture toward this idea, just as the scenes preceding it fail to follow through on the split-consciousness concept. Maybe that’s what lured Cyrus to the project — making big, provocative swings without fully thinking through their implications or significance is kind of her thing.