Two decades ago, X-Men kicked off its superpowered film franchise in what was, perhaps to the uninitiated, an unlikely location: the depths of the Nazi Holocaust. Long before we meet the titular team, viewers are thrust in front of the iron gates of the Auschwitz death camp, where a boy is being separated from his parents. He screams and cries, seemingly to no avail, until a strange thing happens: The gates before him begin to bend and twist in a mockery of physics. The guards, flummoxed or terrified or both, knock the kid out, but he’s not dead yet. Not only does the boy live through his imprisonment, he goes on to become our heroes’ greatest nemesis: the nobly malevolent mutant known as Magneto.

As the current cycle of the X-Men films draws to a close with this week’s Dark Phoenix, it’s worth remembering how it began — with the darkest chapter in Jewish history made manifest. The trauma of the Holocaust wasn’t just the background of some formative interaction, it served as the foundational element of a crucial character. From the jump, audiences are made to understand that the story of the X-Men mythos is, among other things, specifically driven by Jewishness.

But, oddly enough, this was not always the case in the comics from which the X-Men emerged. When Magneto was first introduced in Jack Kirby and Stan Lee’s 1963 Marvel comic book The X-Men No. 1, Judaism was nowhere to be found. He was merely a stock villain — a guy who could manipulate magnetic fields and wanted the superpowered “mutant” offshoot of humanity to reign supreme. Fans of the X-Men brand might now take for granted Magneto’s origins as a Jewish Holocaust survivor, but this particular drive to save the mutant minority from genocidal hatred didn’t come into play for the character until 1981 — a full 18 years after his debut. More than anyone else, one man was responsible for this change: a Jewish boy with the distinctly Gentile-sounding name of Chris Claremont.

That’s right, geeks of the world: Chris Claremont is Jewish. He’s world-famous among comic-book nerds for revolutionizing and defining the X-Men while writing them nonstop from 1975 to 1991. His father was a British non-Jew, but his mother was Jewish, so by the laws of Judaism, which favor matrilineality, Chris has been a Jew from birth — albeit, a nonreligious one. In fact, in 1971, the young Claremont went to live for a time on a socialist kibbutz in central Israel, Netiv HaLamed-Heh. It was there that the depth of the agony of the Holocaust for its survivors first struck him.

“The weirdest, most eloquent memory I have of the time on the kibbutz is, every Saturday night was movie night, and one of the first movies I remember seeing there was Judgment at Nuremberg,” Claremont tells me over the phone. “In that kibbutz were more than a few survivors of the Holocaust. And watching Richard Widmark up there doing his speeches, and showing footage, documentary footage, of the camps …” He trails off for a moment. “I mean, I can’t describe the silence in the room. It was like the air, the noise had just been inhaled. There was no sound at all. It was weird. It was terrifying.” It was in that moment that he learned a well-worn but potent truth. “Those who do not learn from the lessons of the past are destined to repeat it,” he says. “It’s something I’ve never forgot, and I hope I never will.”

Once you know about Claremont’s Jewishness, a number of elements of his fabled X-Men run make a lot more sense. Claremont used Israel as a backdrop for his stories on a number of occasions and introduced a variety of fascinating Jewish characters, including the iconic teenage recruit to the team, Kitty Pryde, as well as Israeli Jews like Holocaust survivor and diplomat Gabrielle Haller and her massively superpowered child David Haller, a.k.a. Legion (whose father is X-Men leader Charles Xavier). And, of course, there’s Magneto.

There wasn’t much in the way of motivation for the supervillain when Claremont took on the writing duties of the low-selling X-Men series a few years after he left the kibbutz. “He was your typical melodramatic, I guess, megavillain, for want of a better term,” the scribe recalls. “He believed in mutant supremacy. There was no reason given for it.” That said, this was the very belief that placed him in diametric opposition to Xavier and his dream of mutant-human coexistence. In Claremont’s eyes, there was potential for Magneto’s future there, if only he could surmount one obstacle: a somewhat bizarre, pre-Claremont story that ended with Magneto de-aged to the point of a baby. The X-Men were, meta-textually, left up a creek. “Every significant book at Marvel had its key antagonist,” Claremont says. “The Fantastic Four had Doctor Doom; Spider-Man had Doc Ock, among others; Thor had Loki, if not Surtur. Without Magneto, the X-Men had nobody.”

So began Claremont’s attempt to bring the Master of Magnetism back. He concocted some sci-fi mishegoss to return the antagonist to his adult status in the late 1970s, after which the character started tussling with various X-folks. His origins, however, remained obscure. It was only in the early 1980s that Claremont and his artist and fellow creative force, the late Dave Cockrum, came up with their master stroke. “We wanted to reenergize Magneto and redefine him in a way that made him a more credible adversary, but also a more credible person, in the same way that we embarked on doing that with the new team,” Claremont says. “Y’know, if we’re going to define a more rounded Wolverine and Nightcrawler and Ororo and Colossus” — all members of the X-Men — “then we could not leave their adversary in his original vacuum.”

In Claremont’s recollection, the next step was “essentially sitting down and figuring out the who, what, where, when, and most especially the why of his life and his origin.” It had already been established in previous comics that Xavier had fought in the Korean War and was roughly the same age as Magneto. “That meant that Magneto had to have come to adolescence, and possibly come of age, in the Second World War,” Claremont says. “And he certainly looked European. And what would have given him such an extreme attitude toward mutant-human relations? Bingo.” It was one of those great moments that hardly ever happen outside the iterative arts of superhero comics and fan-fiction, moments where writers pick up the batons left by their predecessors and create backstories that the characters’ original creators had never intended — but that, nonetheless, fit perfectly. As Claremont puts it, “The next corollary was, Oh. The Holocaust.”

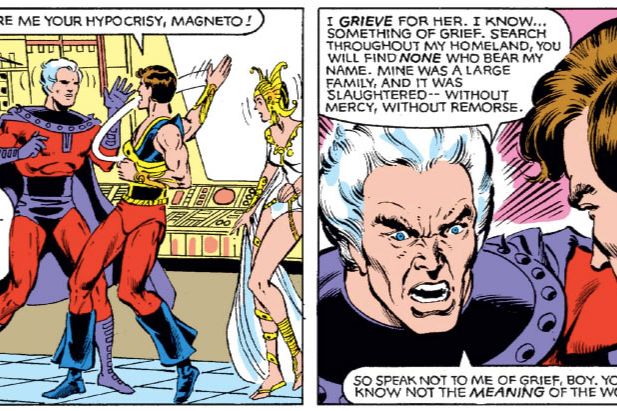

Next came a fateful snippet of dialogue in August 1981’s Uncanny X-Men No. 150. The story bore the simple, evocative title of “I, Magneto …” and, as you might expect, centered around a confrontation between the X-Men and their most notable enemy. Early on in the issue, Magneto speaks to captured X-Man Cyclops, who has recently lost his ladylove, Jean Grey. “I know something of grief,” Magneto barks. “Search throughout my homeland, you will find none who bear my name. Mine was a large family, and it was slaughtered — without mercy, without remorse.” That vague allusion is followed by a more specific one later in the issue. As the X-Men battle Magneto, he strikes down Kitty. He immediately regrets his action when he sees how young she is. “I remember my own childhood — the gas chambers at Auschwitz, the guards joking as they herded my family to their death,” the haughty villain says in regretful soliloquy. “As our lives were nothing to them, so human lives became nothing to me.” Suddenly, he has a change of heart. He realizes how hypocritical his actions over the previous 149 issues have been and disappears from the scene, his entire philosophy in question and a key fragment of his past revealed.

You may notice something absent from that revelation: the word Jew. Throughout Marvel’s history, religion had been a major taboo, so one might assume that the vagueness of Magneto’s background was an editorial directive. Not so, says Claremont. “The reason we decided to err on the side of tact, discretion, use whatever word you like, in that regard, was that we weren’t playing with our character, per se,” he says. “He was a preestablished character, a Stan character, a Stan/Jack character. So we didn’t want to mess around with the core of his origin to that great an extent, certainly without getting a green light from Stan.”

But there was another consideration, he says: “I wasn’t sure how it would play, how I wanted to make it play.” He opted to keep things a little ambiguous in part because he aimed to honor all victims of Nazi horror. “I wanted to keep everybody wondering exactly where we were going to land with this, partly because on one level, the Holocaust is a uniquely Jewish experience, but on another level, it was also, in European terms, a more universal experience as well,” Claremont says. “The Holocaust was specific to Judaism, but it also embraced a significant number of other minorities.”

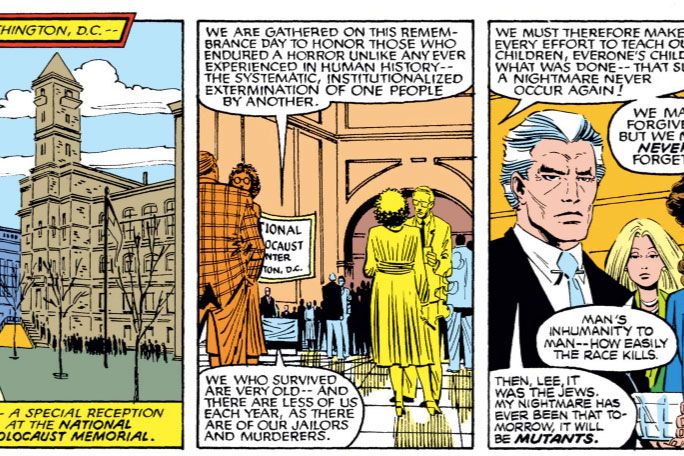

And so, throughout Claremont’s run, it was never made explicit that Magneto was Jewish. However, after the revelation of his Auschwitz background, he turned toward the light, feeling grief for his actions and walking a hero’s path. There were more than a few stabs in the direction of his ethnicity, such as the character’s fateful and emotional visit to the newly established U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1985’s Uncanny No. 199 and his subsequent decision to turn himself in for trial by the authorities of the world; and the time in Uncanny No. 211 when he hears that the mutants known as the Morlocks are to be exterminated and he cries, “No! The horrors of my childhood, born again, only this time, mutants are the victims, instead of Jews.” There were more and more hints, which you can find in this list of references — now out of date, but still useful. You would’ve had to be a fool not to assume Mags was Jewish, but there was still plausible deniability.

That ambiguity proved to be a handicap after Claremont left the X-Men in a huff in 1991. He abandoned his beloved characters in no small part because, as he recalls, Marvel editorial demanded that he turn his regretful and repentant Magneto back into a “badass” villain again. “You know, you spend the better part of two decades trying to make him a hero, and you get that platform pulled out from under you,” he says. “It’s like, Well, screw it. Even I have limits.” For whatever reason, Marvel went on to explicitly state that Magneto was a member of the Roma minority, which was also targeted for genocide by the Nazis. That reveal was later rescinded; it was a mere cover story that Magneto had adopted. Bizarrely, it wasn’t until 2009’s miniseries Magneto: Testament that Marvel made it canonically explicit that the character is Jewish. But by then, mass audiences had long accepted Magneto’s Jewishness thanks to the X-Men movies. Claremont thinks that decision was “a superb choice” on the part of the filmmakers.

Decades on, Claremont has a larger problem with how the cinematic adaptations, capped off by Simon Kinberg’s Dark Phoenix, shook out: He says the films didn’t focus enough on the kids. The titular team was comprised largely of adults and, although we see young students at times, they and their growth are rarely the focus. “The essence of the story, of the concept, should be on the kids,” he says. “And kids aren’t that certain. Kids aren’t that defined. Kids are always questioning. We need to see that. We need to understand that.” And it is here that he ties the loop back to the ethno-religious tradition that he shares with the supervillain he redefined and made iconic: “We need to get into that because, in the classic Hebraic tradition, you’ve got to ask questions,” Claremont says. “If you ask the questions, you get the answers that will lead you to the truth.” He pauses. “Hopefully.”