Back in the day, we would never have imagined that the voice of Bobby Hill on King of the Hill would become one of the most uncompromising and original writer-directors, in television or on film. But life is filled with surprises, and Better Things is the biggest one yet in Pamela Adlon’s career, a long and winding résumé that started with a rejected application to New York University’s film school, then took her to stage, screen, and voice-over acting, and finally to screenwriting and directing (by way of FX’s Louie, a series from he-who-shall-not-be-named, and whom Adlon doesn’t discuss publicly anymore).

Adlon’s half-hour FX series, which recently finished its third season, is a sharply observed account of Samantha Fox (Adlon), a divorced voice-over and film actress struggling to raise three strong-willed daughters (Mikey Madison, Hannah Allgood, and Olivia Edward) while living across the street from her dotty mother Phyllis (Celia Imrie) and navigating the often-treacherous world of middle-aged dating. Adlon’s singular voice unites it all in the manner of the most exacting actor-filmmakers, including John Cassavetes, a primary influence. The organizing unit of Better Things is the moment, more so than the scene or the episode — a quality that it shares with other FX series, including Atlanta, although arguably Adlon pushes this tendency further than anyone else working in the half-hour format, often putting the focus of a scene where you wouldn’t expect it to go, just to see what happens and letting moments of connection or disconnection stretch out via expressionistic filmmaking, free-associative montages, and unbroken, often trancelike musical cues.

We talked to Adlon at length about her filmmaking influences, the show’s tight interweave of biography and fiction, and the importance of self-education and trusting your inner voice.

How did you learn to be a filmmaker?

I went to film school, or I should say I tried to get into the Tisch film school at NYU. I had made a documentary film. I shot it on 16mm and I cut it on 16mm. And I still didn’t get into Tisch! So instead of going to film school, I went to the video store in my neighborhood. I consumed film noir, I consumed every documentary I could get my hands on, the movies from the 1940s, all the independent films. I went through all of John Cassavetes.

What was it about Cassavetes that stood out to you?

It felt documentary. I love watching a film like Love Streams. Hearing those kinds of conversations that sound like real conversations. Hearing somebody say that seeing dirty dishes in the sink in the morning makes him wanna throw up. I had never heard anybody talk like that in a movie before. And the arguments! I just was so drawn to all of that — the discomfort of being able to see these private moments in people’s lives. Total hero, Cassavetes. Total hero.

It’s fascinating that you tried to get into film school with a documentary. In the opening of Better Things season three, where Sam takes her daughter to school in Chicago, you’ve got still photos and snippets of footage in black and white, and then the color comes in. It’s like a little taste of American documentaries from the 1970s.

I’ll take the compliment, but honestly, that looks the way it does because of the parameters of my budget. I wrote an episode set in Chicago this season. I also wrote an episode for New York. I couldn’t go to either place. For Chicago, we shot downtown L.A. When we got into [the editing], I realized I needed more. So I got my Steadicam guy and a friend of his to come with me, and I took Mikey [Madison] to downtown L.A. and we shot those photos.

What do you take away from an experience like that?

When you have parameters, you really are forced to be more creative. Same thing with the airport in that first episode. That’s the airport in Oakland with this big, giant fucking stained-glass wall. I was like, “Ugh, God. Everybody is gonna know this isn’t Chicago.” And then I’m like, “Fuck it! It’s Chicago.” That is something that I’ve learned to do in the world of my show — just say, “This is what this is.” You bought it, didn’t ya?

Yeah, I did. Does it bug you that you don’t have a big budget?

Not always. Restrictions are sometimes a good thing, because you can really just go to the most creative place — somewhere you didn’t think was possible.

I have Turner Classic Movies on a loop, religiously. On my show, any time you see a TV screen, it’s always on TCM. My show is set in a world where people love to watch old movies. You know how movies were more frank about things back in the 1930s before the Hays Code came in? Well, sometimes I get restrictions, too. So I just pretend I’m working under the Hays Code and think outside the box.

If you’re game, I want to throw out a few moments from season three, and you can tell me whatever pops into your head about them?

Sure.

Tell me about the scene in that first episode where Sam and Max are in the drugstore, shopping for her dorm room.

I wrote that scene to be set in a Target. Not only could we not get permission to shoot at Target, we could not get one single box store to let us shoot in them. Nobody wanted us! No Target, no Big Lots, no K-Mart. Then I drove past this weird old pharmacy in Burbank. I walked in there, I scouted it myself, and we ended up shooting there.

In the drugstore, you exchange point-of-view shots between your daughter and a homeless woman. Why did you include that?

I like details that are not, as they say, “on story.” Also, touches like that were a way of drawing to the fact that so much of this show is about excess. You know? In the store, Sam’s got three carts filled at this point. You know Max is about to go into her life, and meanwhile, here’s this other woman. Who even knows what her life has been like? She’s got a shopping cart full of trash, and Max has a shopping cart full of hope and new possibilities, but it’s also filled with excess.

Why point out all the excess?

Because I would read comments online, like, “She’s got all this money, and she could get her kid this and that.” I’m not trying to make Sam Fox a perfect person. It’s far more interesting to see her fail, and also make you aware that she’s surrounded herself with this excess that a lot of people would think of as wrong.

At the end of the episode, Sam goes home and reads Raisin in the Sun to her middle daughter, Frankie. Where did that come from?

That happened with me and one of my daughters. It was at the end of a night and she was like, “I have to read this whole play.” And I was like, “Seriously? The whole fucking play now? It’s ten o’clock at night!”

Instead of freaking out, Sam takes a breath. She just dropped her off daughter at college. Her plane was literally on fire — she had to make an emergency landing. Finally she gets home and there’s 40 people downstairs that she doesn’t know. And she just takes a breath and says, “Okay, I’ll read one part, you read one part.” It still gives me chills to think about it.

And that play is so good. It resonates. The way those passages lent themselves to the world of this family and this show was what I call “a Better Things thing.” A magical little thing that fits right in.

Episode two has the weed-saturated dinner party. How, as a director, do you shoot a scene in a tight space with so many speaking parts in it?

We wanted to have a sequence where Sam was cooking and people were coming in and out of the place. Being home and having a whole village there is a big part of my life. I like to see that onscreen, but shooting it is very difficult. I said, “We can’t all fit in the dining room. Let’s stick us in the living room.” I put Sharon Stone and Greg Cromer on the floor, which I love because it just makes it so intimate and cozy. We moved furniture around.

You don’t worry about the layout of the house changing from one episode to the next?

I’ve learned that you don’t take a room literally. You gotta be able to go, Can we just blow up that whole wall? Can we put this over here?

What about the scene in the garage?

I wanted to have a scene with Kevin [Pollak] and Diedrich [Bader] smoking pot in a small area, so I just threw them in the garage. And let me tell you something: The greatest thing about doing what I do is that I don’t have anybody second-guessing me and going, Why would they be in the garage?

Maybe they’re regressing. That’s where you would smoke weed if you were a teenager, right?

Yes! But it doesn’t even have to be explained. If they sneak off to the garage, especially if they don’t have to, that’s funny.

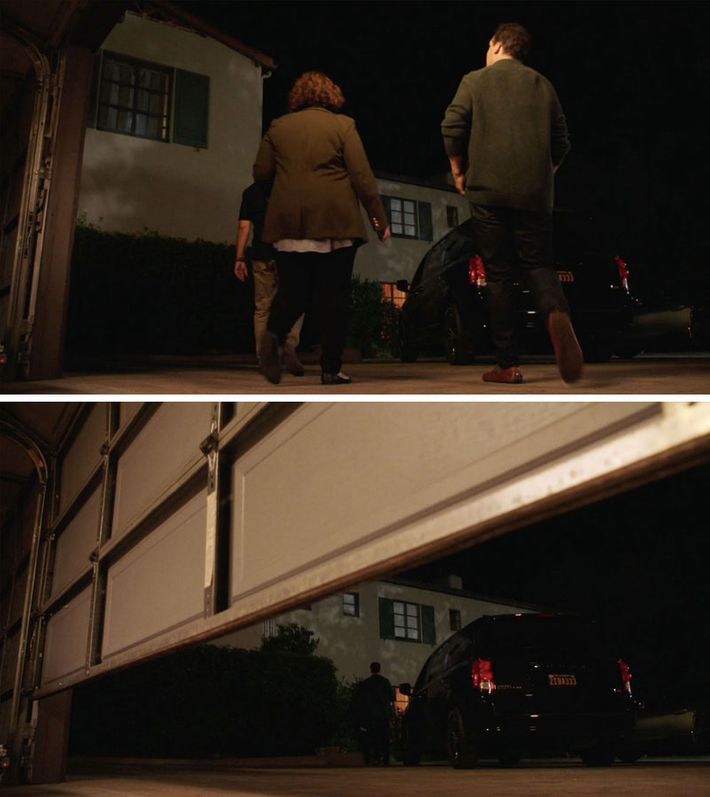

One of my favorite shots in the season is when they leave the garage after smoking that powerful weed. You stay on them as they’re going back to the house while the garage door closes. They’re getting smaller in the frame, and you’re hearing them but barely seeing them.

I love that shot. That came about because we had to contend with the timing of the garage door opening and closing. We liked it, so we went with it.

In episode three, how about the confrontation at the elementary school? “Do you know how many kids you almost hit?” Where did that come from?

The confrontation scene comes out of my dealing with a lot of parents and having a lot of frustration through the years. Sam Fox is living out Pamela’s fantasy. Sam is like me in a cape. She’s Super Pamela.

Do you have kids?

My wife and I have four teenagers in the house.

Holy shit.

So to me, this show is a documentary. You can institute all the disciplinary crackdowns you want, but they’re still gonna fight you.

That is absolutely true. I’m going through it right now because my kids are all getting older. It’s like what we said in the girls’ night out at the restaurant: We’re obsolete. You just know they’re all rolling their eyes at you.

Constantly.

And I’m like, I see you, you kids. All of you! I see all of your fucking eyes rolling in the back of your heads all the time. And yet they’re still your kids. They still want and need shit from you. So it’s all a bit frustrating. I like showing how love still exists in the middle of all that.

About the fourth episode …

Oh, boy. Here we go.

Where did the idea for this episode come from, where Sam dreams about her ex-husband raping her? That’s disturbing stuff.

Well, yeah!

Can I ask you about the origins of that?

I was in the kitchen, shooting [the season-two finale] “Graduation,” and the idea just came to me. I turned to one of the camera operators and I said, “Write this down: My ex-husband is raping me repeatedly in my dreams.”

Without context, that’s quite a statement.

I know! I didn’t know where that idea was gonna lead, or how I was gonna weave it all into season three. But it turned out great. It led to Sam going into therapy and to Matthew Broderick being on the show.

It also led to a sexual encounter between Sam and her ex, which is not necessarily an outcome that some viewers would consider healthy.

Exactly. [Director of photography] Paul Koestner got off so hard on that — I mean in terms of shooting it! That place was so cinematic. I wanted it to feel like we were watching American Gigolo or something like that — like a Paul Schrader film. The sex, the danger, the mystery. It was hard to have it feel more mysterious than salacious, you know what I mean? The question we were asking was, “What is this thing that Sam wants to get out of her system and has no control over?”

How did you answer that question?

I gathered all my female crew members around me and said, “What should we do?” I was taking polls about what I should do with my body, how we lit the bed with that shaft of light, finding a piece of music to go with it. The neon light in the bathroom added another element to it. It’s a gorgeous sequence. A weird, nighttime, sex movie thing.

In the next episode, Sam gets a colonoscopy. You have scenes on this show where you’re in your underwear, or in a hospital gown, or sitting on a toilet. As an actor, are you way past being uncomfortable on camera? Or do you ever have moments where you feel awkward or exposed?

Are you fucking kidding me, Matt? [Laughs.] Scenes like that are much more comfortable than the hotel scene we just discussed. I’d much rather be on the toilet than writhing around on a bed in my underwear!

Are you ever yelling at the crew from the toilet? “Move that light over here!”

All the time!

I wonder if Clint Eastwood ever has moments like that.

Maybe on Play Misty for Me. The deleted scenes.

Tell me about the moment in the Easter episode where Sam’s mom talks about getting older. She says that when you’re attracted to somebody new, the question changes from “Are you married?” to “How married are you?”

That came from one of my writers, Robin Ruzan. We were talking about how hard it is to start something new when you’re older because your options narrow down. When you’re younger and you meet some guy, you’re like, “I don’t like him, he smells,” and you can just cut bait and run. When you’re older, your options are limited but your standards are so high, so you have to become more realistic.

I can’t believe I’m about to say this, but that moment between Phyllis and her new boyfriend’s wife, who has dementia, is so touching. They’re watching Easter Parade, they start singing along with it, and you move the camera back and forth between them as they sing. It’s another Turner Classic Movies moment — they really should be paying you for all this advertising.

I knowwwwww! We wanted to actually show a scene from the movie, but we had to settle for just having them sing along with the audio.

I didn’t realize until this very moment that you never see the TV.

In the end, the scene is so alive that you don’t need to actually see the clip. The point of that scene is the women. One of them is caught in her own world in her head, and the other is desperately trying to connect. There’s a lot going on there.

That’s putting it mildly.

Yeah!

A lot of your show is not easy to navigate for viewers. People make bad and sometimes alarming choices. Sam’s ex-husband Xander is a dark presence. And Sam’s dreams seem intertwined with other inappropriate behavior by him in season three, like …

The cell phone.

Xander giving Duke a cell phone just for talking to him, that seems kind of inappropriate to me. It reminds me of Walter White’s second cell phone on Breaking Bad, or something an unfaithful spouse would do to hide an affair.

And when he gives the phone to Duke, the note says, “Don’t tell your mom.”

Which is what a child molester would say.

Yeah, exactly. But that’s one of the things that I like to do, filmically.

Make people not know quite how to feel about things?

Yeah.

How do you know whether something like that is gonna work, as opposed to creeping out viewers and getting you in trouble?

I don’t. I’m just learning.

Oh, come on.

No, I really mean that! I don’t pretend to always know what I’m doing or what the effect is gonna be. An “auteur” is what people call me, but I don’t know how I feel about that.

If a woman who writes, directs, produces, and stars in her own show isn’t an auteur, then what is she?

Somebody who knows what she likes and is able to put it up onscreen.

How are you able to achieve that in a business that tends to be inhospitable to personal expression, particularly when the filmmaker is a woman?

I figure out what I like, and how I want to get to what I like, and then I go in that direction. It helps that I know how to get yeses. I can get past a lot of no. And if it’s an absolute no — well, maybe if we just talk about it, get creative, we can figure out how to do the next best thing.

The two words that I say to my crew at the beginning of every season are “human interaction.” That’s everything for me. And that’s why this is a show about moments. The moment is everything. It doesn’t have to be the obvious moment. That was something that my network had to get in order to understand my style as a filmmaker. At first, they would give me a note that wasn’t right for the show.

Can you give me an example?

In season one, I have a scene with Sam and Xander at a restaurant. He says, “Will you help me with the girls?” And Sam says, “You want me to help you let the girls know that you’re not gonna be around to see them, even though you’re [here] in California?” And then Sam stands up and leaves, and I keep the camera with Xander.

The network note was, “We want to leave the scene with Sam because it’s more powerful.” Luckily, [FX] is a place that gives notes but doesn’t mandate them. So I kept the camera on Xander because I wanted to see what that guy was thinking.

That’s not how that sort of scene is usually played.

No, it isn’t. But it was more interesting to me to play it that way.

What can you tell me about the scene where Frankie confronts her mother about never explaining her separation from Xander? It erupts all of a sudden, and it’s obviously been simmering for a long time. Why that scene, and why there?

I don’t know. A lot of people want and need explanations for stuff like that, especially when you’re doing a TV episode or a movie screenplay. They want to know, “Why is Sam behaving this way? Why is Frankie doing this?”

For me, that scene is about how big, giant emotional things can come up in your life, but then you go back to normal. It could literally be the worst day in the world, a day where everything falls apart, and then you wake up the next morning and one of your kids will be like, “Hey, dad, I need a ride.” And you’re like, “What?” And then you realize, “Oh, right, it’s over. Yep. The worst day. And now we’re on to the next day.” And you gotta deal.

In that same episode, after Max experiences a major breakup over the phone. Sam puts aside her own stuff and decides to be funny and disarming.

Same kind of thing. She sees her daughter in peril and makes up a funny song.

There’s a lot of phone-related parent-child drama on this show.

I never know what the fuck is going on in those phones. The kids, they’re having conversations with six different people at the same time. You never really know who they’re talking to, and you never know if they’re gonna let you in on what’s really going on with them.

All that stuff on the show is just symptoms of the way we live today. If I’m sitting talking to one of my daughters, I’m like, “Hi, hello. Can you look up here, please?” And they’re like, “There’s something going on, Mom, you don’t understand. I can’t right now.” And they’re on their phone as they’re telling me this. And I’m like, “Well, what’s going on?” And they’re, “Mom, stop.” It could be a really important thing, or it could be a nothing.

Sam has a line in the fourth episode of this season where she says life is better without a phone. Do you agree with her?

Oh God, yes! Are you kidding me? Without their phones, kids would be able to read entire books, and concentrate better in conversations, and they’d have better self-esteem because they wouldn’t be constantly comparing themselves to each other. It’s a nightmare!

In the fifth episode, where did the idea for a “girls’ night out” come from?

The girls’ night out was actually the first thing that I ever wrote for my show, before I even had a show. It was an experiment to see if I could find the voice of the show. I didn’t put it in season one because I really didn’t see Sam being able to have a life like that, not at that point. In season three, I realized it was time, so I brought it out of mothballs. We ended up shooting it on a thing called National Girlfriends Day, and I was like, “This is crazy. This is a Better Things thing.”

As for the idea behind it, I wanted to show these middle-aged women just releasing, having fun, and saying horrible realities to each other. Stuff you’re not supposed to say. I still can’t believe some of the stuff that came out of their mouths.

The friend who has twins tells Sam, “I like one of them.” And Sam says, “I like one of mine, too. I’m not naming names.”

Yup. These are the dirty little secrets that we all walk around with.

How much do you worry about Sam being perceived as Super Pamela?

Do you think she is?

Yeah, but that’s not a knock on her. I’ve known parents like her. They don’t come along often, but they’re out there.

Well, I like that and I appreciate that. But the truth is, I’ve had people make comments to the effect of, “She’s too permissive,” or “She’s just letting everybody steamroll over her.”

Do you agree with that?

No, I disagree. I think she’s really doing the best she can. I used to say that the tagline for my show should be, “Life is what happens to you when you’re busy making other plans.”

John Lennon?

Yeah, “Beautiful Boy.”

In the season finale, Frankie runs away after years of challenging her mother’s authority. Sam’s reaction is … well, ultimately, she adapts to it? If you’re concerned that viewers see Sam as too much of a permissive parent, this is quite a gauntlet to throw down.

Here’s the thing. Sam is a single mom. She’s in agony. She’s checking up on her daughter. There are texts about “Frankie sightings.” All of Frankie’s friends are keeping Sam in the loop. It’s only Frankie who’s not. And through these reports, Sam knows that Frankie is going to school, she’s not in danger, she has support. People are looking at it in a way of, “Her child moved out,” or “Her child ran away,” but it’s a different thing. Frankie is taking control of her life. Sam can only be there to the extent that Frankie allows her to be there.

I don’t know what this says about me as a parent, but when I look at what Frankie did, I’m impressed almost in spite of myself. You need your shit together to pull something like that off. To me, it says Sam did a good job raising her, even though Frankie proves it in a way that’s very stress-inducing.

I agree. Frankie is a strong, sensitive character who wants to hurt her mother for some reason, which is something that happens in life all the time.

Why do you think Frankie wanted to hurt her mother?

I don’t know. We never really know what’s going on with our kids, even if we think we do. And this kind of thing happens when you’re a single mom. In situations where parents have split up, the parent who’s always there is the one that takes the hit. The kids want to know they’re safe, but they also want to know that they can push really hard. That’s how they test the strength of the bond. That’s the dilemma of the single parent. That’s what I’m trying to portray.

So, bottom line: Life happens, and you roll with it?

Yeah, you can’t control it.

It must be cathartic for you to do this show.

FX is paying for my therapy.

Better than the other way around!

Way better! Because it’s not just my therapy. It’s your therapy, and it’s your wife’s therapy, and it’s therapy for any of your kids who might watch it.

What’s the best reaction to Better Things that you’ve gotten?

I have this writer’s assistant. He’s 23. He said, “I’ve started calling my mom more.”