Every summer at the movies brings with it a whole host of CGI creations, many of them lumbering monstrosities capable of destroying a major city with a single step. What a delight it is, then, to encounter Forky, a character that is basically the exact opposite. As seen in Toy Story 4, he’s a craft project whipped up out of a spork, a popsicle stick, and some pipe cleaners, who comes to life basically against his own will. Forky is a strange, surreal creature — possibly the first time a children’s movie has ever dealt with a “Man vs. God” conflict — and as voiced by Veep’s Tony Hale, he’s also one of the most winning: Who wouldn’t want to embrace this bizarre creature who spends the bulk of the film attempting PG-rated suicide?

The Birth of Forky

The story of Forky began in the early development of Toy Story 4. As those making Toy Story movies often do, they were discussing toys. On this particular day, says director Josh Cooley, they were sharing a common parental complaint: You spend all this money buying your kid a Christmas present, and then they’d rather play with the box than the toy. They started brainstorming objects that weren’t quite toys, but could become them with a little imagination. A rock? Or how about a spork? Sporks being a universally recognized object of comedy, they went with the misbegotten utensil and never looked back.

If Forky is a spork, why is he called “Forky”? That idea was inspired by Cooley’s family, too. The director had shown a picture of the character to his son, who suggested the name “Forkface.” For obvious reasons, that wouldn’t do, but the notion that a child, having no reference point for a spork, would immediately peg it as its more common brethren stuck. Casting was pretty simple, as well: The character was intended as an overwhelmed neurotic, constantly exploding with anxious energy, so naturally, Tony Hale was the first choice. (“Yeah, that tracks,” says Hale.)

Upon signing up, the actor began a series of sessions with the filmmakers to discover what Forky was all about. “Typically when you do animation, you’re apart from everybody: They put you in a separate room and you have headphones, then everything goes quiet and you’re kind of by yourself,” Hale says. “Whereas with Pixar, they put everybody in the same room. It was kind of a workshop mentality. Everybody was throwing stuff out, we were trying different voices.”

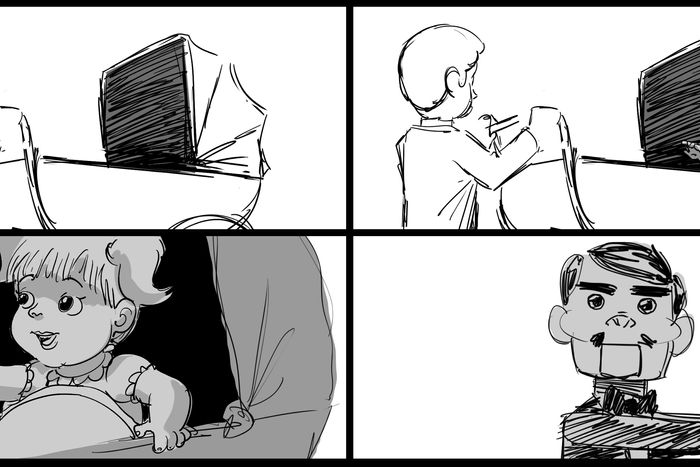

Initially, the plan was for Forky to make his first appearance during the toy roll call in Bonnie’s room early in the first act. He would have stepped forward and introduced himself, almost like a new employee: Hi, I’m Forky, I’m not really sure what I’m supposed to be doing. However, Cooley recalls, “we realized we weren’t giving the audience that moment” of seeing him come to life. His story would be more powerful if the audience could get to know him from the moment of creation. Eventually the writers dreamed up an entrance that would give both a “jump scare” for the audience, as well as emphasize Forky’s fundamental existential confusion. “He’s like someone who’s been saved from drowning,” Cooley says. “Where am I?”

Regarding the specific mechanics of what brings a toy to life, cast and crew prefer an emotional answer to a metaphysical one. “The thing about the Toy Story universe is that every toy has a purpose,” says Cooley. Ultimately, it’s that purpose that gives them an inner life. As Hale puts it: “When somebody comes in and says, ‘You are a toy,’ you are now a being worthy to be loved, then you come to life.” (Keeping the “how” of toy consciousness vague also led to Forky’s final line, one of the biggest laughs in the film.)

The Evolution of Forky

More fun was imagining all the different beats you could play with Forky. As important as his conviction that he was actually garbage was his sense of childlike wonder. “Not only did he not want to be a toy, he never thought he was going to be alive,” Hale says. “This is not even close to the framework of what he had in mind.” To play it, Hale drew on his memories of what his daughter was like when she was a small child: “Everything was a question, and there was no shame about asking questions.” Alongside this came an innocence, a lack of judgement, which allowed the filmmakers to draw out melancholic, even sympathetic notes in the character of the film’s antagonist, Gabby Gabby. Finally, they added comedic grace notes where Forky turns out to know more than you’d expect, finishing Woody’s sentences and demonstrating a surprising level of emotional intelligence.

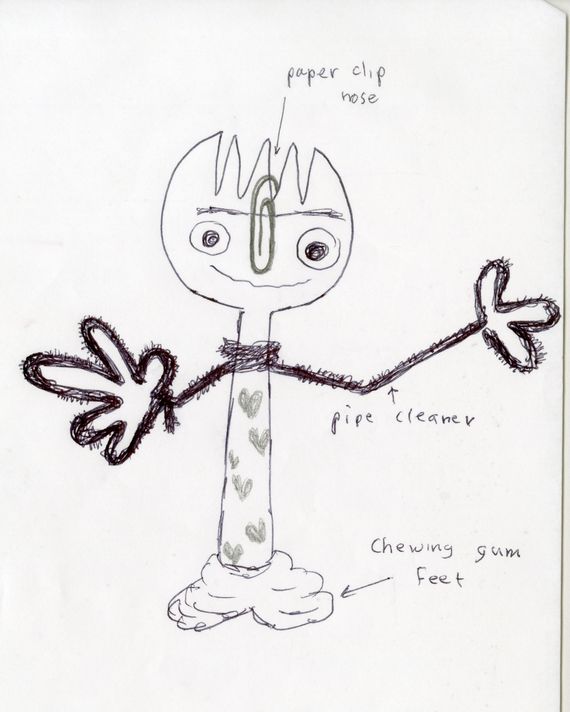

Once written, animating Forky came with certain challenges. A stuffed cowboy can move his lanky limbs in all sorts of ways; a spork with popsicle sticks for legs is comparatively more limited. For animator Claudio de Oliveira, Forky’s movements needed the combination of “being true to the materials he was made with, but keeping that childlike playfulness.”

To experiment with the character’s movements, de Oliveira found himself making his own model Forkys and taking them home. “I started feeling for him in ways that I didn’t expect,” he says. “I was trying to glue his eyes to his face, and all of a sudden one of those googly eyes would drop down and look straight at me.” (Once he took the model back to work, he started getting texts from his family, wondering where their beloved spork had gone.) The limitations turned out to to be a creative boon: De Oliveira determined that Forky would move his body as rigidly as anyone with an unbending plastic backbone would, with the necessary spark supplied by his gonzo facial expressions. “The way that he moves his mouth, it’s a very particular burst of energy on every little different mouth shape,” the animator says. “I was trying to infuse that kid energy of always being on their tippy-toes.”

Forky Lives

After years of playing the nearly silent Gary on Veep, Hale relished the opportunity to embody a character whose voice was all he had. In the booth, he found himself acting out Forky’s own physical struggles. “He has no flexibility in his body. Even his eyes are out-of-control,” the actor says. “Having done a lot of animation, you almost have to do the same physicality you would if you were on camera. That energy needs to be channeled into a microphone. You don’t have a raised eyebrow, or a certain look.” Hale’s vocal performance in turn helped the animators realize just how far they could go with the character. “Specifically when he was recording the word trash, he had so many takes on just that word,” de Oliveira says. “It showed us how we could stretch and pull on very minimal movement and cultivate a certain emotion, and that emotion would be unique and singular to Forky.”

“Unique” and “singular” turned out to be right — Forky is one of the strangest characters to appear in a summer blockbuster in ages. He’s a fan favorite, an anxiety icon, an easy craft project for exhausted parents looking for something to do while the kids are out of school. He’s also important representation for a plastic utensil that has been subjected to nearly continuous mockery since the day it was invented.

The experience seems to have converted at least one person to Team Spork. “There is something very gratifying when somebody hands you a spork,” says Hale. “It really ups the ante. Not only can I scoop up this broth, but I can stab the meat. I have a whole new purpose for my utensil. It’s very underrated — there’s a nice little joy you get with a spork. It needs its own moment.”