According to the GIF-hosting site Giphy, this GIF of the character Patrick from SpongeBob SquarePants has been viewed over a billion times. In it, a 3-D image of Patrick Star, a lovable and not especially bright starfish, lies on his belly with his hands on his cheeks. His eyes are wide, adoring, and the GIF’s nearly indistinguishable looping means that his feet are perpetually kicking back and forth like a metronome. Around him, pixelated pink and magenta hearts pulse insistently in time with his feet’s movements. Patrick is in love.

Sad Patrick also has over a billion views on Giphy; in this GIF, Patrick’s mouth is curved into a zig-zagging frown, and his eyes are half-full of tears. Happy Patrick, waving a flag and foam finger, has a comparatively meager 58 million views.

What is it about Patrick that makes him so eminently GIF-able? Giphy’s viewing data suggests that the most viewed of their TV channels in 2019 — the collections full of GIFs from individual TV shows — are from Saturday Night Live, SpongeBob, Fallon’s Tonight Show, Game of Thrones, Broad City, and The Bachelor. What is it about those shows that make them so ripe for harvesting GIFs?

The first part of the answer lies in how these GIFs get used, and the SpongeBob examples are prime illustrations of what makes a GIF effective. They are quickly legible in almost any context. If you’ve seen SpongeBob or if you haven’t, if you’re looking at the GIF while quickly scrolling through your feed, if you speak any language — those images will translate. They are representative of a few very common emotional responses — I love you/this, I am really upset, I am happy — and in the manner of most internet communications, they are appropriately hyperbolic. Not just “in love,” but surrounded by pulsing hearts. Not just “sad,” but teetering on the verge of sobs. Not just “happy,” but waving a foam finger. There’s something ineffable about Patrick’s expression and the pulsing hearts that surround him that say “I truly love this” just a tad more emphatically than the words alone would communicate.

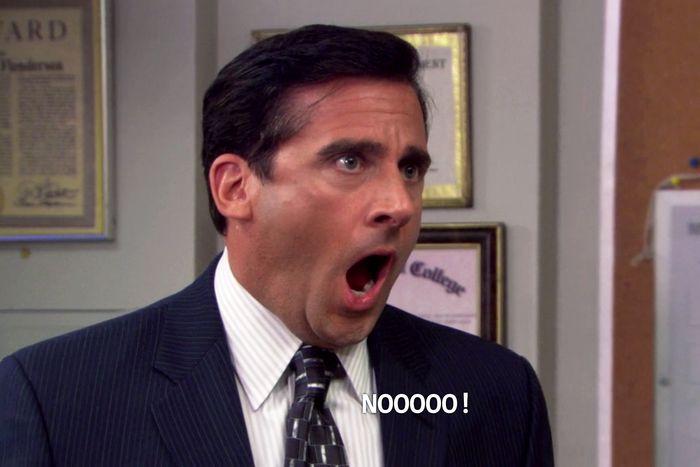

Those SpongeBob images are decent representatives of what it is about GIFs that make them so appealing: They can communicate something that words often do not, and they have become a universal shorthand, a shared language as effective and suggestive as written words. Once they’re out in the world, it’s not hard to see the appeal or the use case. Why say, “I am so disgusted by this that I need it to exit my head as quickly as possible and I regret ever looking at it” when you can use the Michael Scott “NO!” GIF instead? (689 million views on Giphy.) Or if that’s not quite the right version of disgust for you, what about The Bachelor’s Corinne throwing her head backward in some emotional combination of revulsion, annoyance, and boredom? (123 million views.) Or maybe you’re just slightly past the experience of disgust, and are now looking forward to distancing yourself emotionally from whatever damage is playing out beneath you. Maybe you’ve gotten to a place where you’re enjoying the mêlée. That’s more like a Cersei-drinking-wine situation. (47 million views.)

What these short looping clips have in common is that they are distillations of some emotional reaction that can be otherwise difficult to express in words. Looking up “happy” on a GIF search engine is like looking up “happy” in a thesaurus: You are presented with hundreds of variations, thousands of more specific ways of expressing the idea you’re trying to communicate. It is very hard to describe exactly what emotional state is happening in this GIF of a little girl taken from what I’m pretty sure is a TLC reality show, but I know it’s a feeling I have experienced many, many times. The Giphy tags on it are things like “joy,” “delight,” and “smile,” but there’s a way that the girl’s receding chin suggests something else, something like self-effacement or self-consciousness. There’s a moment near the end as her eyes widen where her joy tips over into something a little more panicky, a little more overwhelmed. It is a different kind of emotional response than a simple, uncomplicated GIF of Linda from Bob’s Burgers shaking her hands with glee.

That idea is also at the heart of what makes a show particularly GIF-able. Great GIF-worthy TV is especially accessible for being clipped and excerpted, so that its most dramatic reaction moments are set adrift from their original contexts and made to float freely among the vast GIF collections of various emotional states. Great GIF-able TV requires close-up shots of faces doing elastic, identifiable, difficult-to-express things, shrieking with rage or collapsing with humiliation or looking at the camera in dismay. It’s why this second season of Big Little Lies has felt so comparatively GIF-worthy; its cinematography seems designed to highlight full-frame moments of actors screaming things with abandon, and you could imagine nearly every close-up rendered into GIF form and accompanied by a tweet with the caption “huge mood.”

But that sense of being excerptible — the need for any emotional response to be cut loose from its original context — is also the thing that makes TV GIF-ability a fraught exercise. Once set loose, it’s incredibly easy for a GIF to be divorced from its original framing, forever severed from the ideas and characters and creators who made it. A GIF-able TV show is also one that can be cut up and used for parts, which makes it widely useful but renders its distinctiveness strangely anonymous. After searching for half an hour, I still cannot tell you where precisely my beloved happy-faced-girl GIF comes from, although I suspect it’s Toddlers and Tiaras. And even assuming that’s true, what is the girl’s name? Who is she? When you see her as you scroll past her on Twitter, there’s no way to know.

I can tell you, however, that one of the most viewed GIFs on Giphy, that “Patrick in love” GIF, is not from a TV show. It’s from a movie, SpongeBob SquarePants 2: Sponge Out of Water, and the pixelated hearts have been added by someone after the fact. I do not know who made it, or how long it’s existed. All of that information has been stripped away, and the credit for its creation is never included in its widespread use. The thing that makes a GIF universal also means that it feels personal; its utility is more about how its users feel than about what it was originally intended to mean or who made it. GIFs feel like a shared language in spite of their specificity, in spite of the fact that they are made by a few individuals whose credit may be forgotten. TV and movies are GIF-able when their bits and pieces feel larger than the surrounding stories. They become aphorisms and clichés. They become truisms. TV becomes GIF-able when it becomes a bite-size reflection of something viewers recognize in their own lives.

And with that,