When people ask me to name the greatest production I’ve ever seen of a musical, I don’t have to fish for an answer. It was Harold Prince’s original production of Cabaret in the fall of 1966. I saw it during the first week of its life, when it was trying out at the Shubert Theater in Boston on its way to Broadway. That I ended up in the Shubert was completely by chance. I was a theater-geek high-school senior in town for a college interview; that was the show that was running downtown the one night I had to myself; seats were available in the very back of the house. I knew nothing about the production. There was only one nominal star in the cast — the legendary Weimar-era performer Lotte Lenya, the widow and collaborator of the composer Kurt Weill. There had not yet been any reviews to tell an audience what was in store.

When you walked into the theater, the curtain was up, an anomaly then, and you were immediately confronted by a huge trapezoidal mirror reflecting the arriving audience. Then the lights went down, and out trotted this garishly rouged, terrifying human marionette, an “emcee” played by Joel Grey, an actor then little known except (by obsessives like me, anyway) for inheriting Broadway roles originated by stars like Anthony Newley in bus-and-truck tours. “Wilkommen …” he sang. I couldn’t quite catch the rest and turned to my friend Sara in panic: “Is this show in German?” That happily proved not to be the case, but other shocks were to come. A sudden blast of white lights along the stage apron to temporarily blind the audience at the end of an act. A moment when Grey appeared on a catwalk high above the proscenium, letting loose with a hideous laugh and flicking cigar ash on some young Nazi hooligans frozen in hushed silence on the garishly lit stage below. A creepy shadowplay sequence with the actors casting their distorted images on white front curtains, like a George Grosz painting come to life.

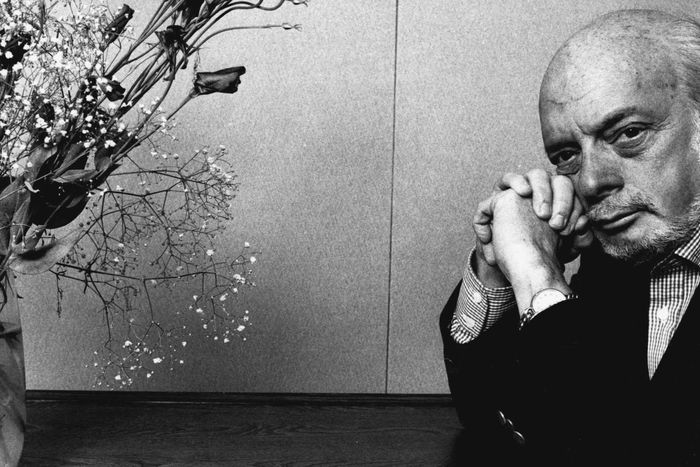

That last effect would be discarded by the time Cabaret opened at the Broadhurst in New York a few weeks later. So would an entire act of what had started as a three-act piece. The show was the better for these changes, but my initial impression of the hit-in-embryo has never receded in memory. In the years to come, there would be terrific revivals of Cabaret (notably Sam Mendes’s for the Roundabout in 1998) and dreadful ones (Prince’s own tacky Broadway revival of 1987), not to mention Bob Fosse’s lauded 1972 film adaptation. Yet none of them were as original or startling as what Prince created at the start. Though it hardly begins to sum up his whole extraordinary career, Cabaret crystallizes what it means to be a great director — and producer — of musicals. Prince, who died earlier today, at 91, was both.

As director, he was responsible for the production’s groundbreaking showmanship and stagecraft, for the casting of Grey and Lenya, and for having the sense to hire the iconoclastic set designer Boris Aronson and let him smash all the design conventions that governed the commercial theater of the time. As a producer, he conceived the whole audacious thing: a musical about the rise of the Nazis, adapted from such very un-Broadway material as Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories, that, without ever being remotely explicit about it, also captured the angst of a contemporary American audience that was caught up in the tumult of the civil-rights movement and just about to be torn asunder by the Vietnam War. To say that this was a risky venture two years before Hair is to understate the case; this was the era of Hello, Dolly! and Funny Girl. To add to the risk, Prince hired little-known songwriters, John Kander and Fred Ebb, whose previous collaboration, Flora, the Red Menace, produced by Prince a year earlier, had folded in less than two months despite the accolades that greeted its young star, Liza Minnelli.

Not everything Prince did was this brilliant or daring, and heaven knows he had his disasters, some of which I had to review as a theater critic in the 1980s. But overall his career stands as one of the most significant in the last golden era of the Broadway musical. It’s impossible, in fact, to imagine that history without him.

It’s only fitting that Prince met his most significant collaborator, the then-19-year-old Stephen Sondheim, at the opening night of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific in 1949, at the dawn of that exciting era they would revolutionize and dominate. As Sondheim was the protégé of Oscar Hammerstein, whose innovative legacy he would build on and make his own, so Prince’s tutelage was provided by the director George Abbott, another Broadway lion whose career dated back to the 1920s. Prince’s early association with Abbott included working for him as an assistant stage manager on Irving Berlin’s last Broadway hit, Call Me Madam, in 1950, and then as stage manager on the original Broadway production of the Leonard Bernstein–Betty Comden–Adolph Green musical Wonderful Town three years later. Forming a partnership with Robert Griffith, a more senior Abbott stage manager, Prince would soon become a full-fledged producer with back-to-back Broadway hits, The Pajama Game (1954) and Damn Yankees (1955), both directed by Abbott and both, like Cabaret later on, with scores by a heretofore-obscure young songwriting team, Richard Adler and Jerry Ross.

If you love vintage Broadway musical comedies, Pajama Game and Damn Yankees hold up just fine and have never been out of circulation. But nothing about them would prefigure the turn Prince’s career would take only a couple of years later, when he and Griffith co-produced West Side Story (1957) after the veteran producer Cheryl Crawford got cold feet. Teenage-gang warfare in New York was as unlikely a subject for a Broadway musical as Weimar Germany would be a decade later, and, as with Cabaret, there were no marquee stars as insurance against box-office failure.

Clearly Jerome Robbins, whose innovative direction and choreography were intrinsic to the success of West Side Story, had a huge influence on Prince’s subsequent directing career. They would team up again as producer and director on what would prove to be Robbins’s last new Broadway musical, Fiddler on the Roof, in 1964. What many forget about Fiddler now is that it, too, was thought to be a huge commercial risk at the time of its original production (“too Jewish” and with a pogrom, yet) and took an unusually long time to line up investors. The original producer, Fred Coe, dropped out along the way, and again it was Prince who came to the rescue. Like Kander and Ebb and Adler and Ross, the show’s songwriters, Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick, had been little known until Prince, with Griffith, produced their first hit, Fiorello!, in 1959. (Bock and Harnick’s previous show had been a box-office flop, the 1963 musical She Loves Me, which has since aged into a classic — though no production has ever topped Prince’s exquisite original staging).

Cabaret followed Fiddler by two years. It would prove Prince’s bridge to one of the most sustained runs of artistic achievement in the history of the American theater: his Sondheim collaborations of the 1970s. In keeping with his championing of young songwriters, Prince had produced Sondheim’s first Broadway musical as composer and lyricist, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, in 1962. Then, in procession, arrived Company (1970), Follies (1971), A Little Night Music (1973), Pacific Overtures (1976), and Sweeney Todd (1979) — all of them daring, not all of them commercially or critically successful at the time, but every one now part of the national (and often international) repertory. Prince directed all of them (with Michael Bennett as co-director on Follies) and produced all except Sweeney. By then he had renounced producing as a career, having seen the financial writing on the wall: The ever-more-powerful theater owners and corporate producers, combined with spiraling production costs, were squeezing out independent impresarios like Prince.

The next Sondheim-Prince collaboration was Merrily We Roll Along (1981), in which Sondheim’s superb score was squandered in a head-scratching Prince production cast with young actors, many of them novices, who were promptly swallowed up in an ugly and calamitous staging. In years to come, Sondheim and the show’s book writer, George Furth, would keep rewriting the show for a series of subsequent revivals, and it has had an afterlife that belies an original Broadway run that sputtered out in two weeks. But after that original debacle, Prince and Sondheim went their separate ways professionally (if not personally) — Sondheim joining forces with James Lapine on Sunday in the Park With George and Into the Woods, and Prince, most notably, with Andrew Lloyd Webber.

Prince’s crackling original production of Evita (a fascists-on-the-rise musical that would never have been attempted had Cabaret not preceded it) is hands down the most creative staging of any Lloyd Webber musical; his original staging of the operetta Phantom of the Opera as a theme-park ride, now having passed the three-decade mark in the West End and on Broadway, stands as the musical theater’s biggest money machine. Interspersed were a number of critical and commercial duds that were sometimes in theory as daring as Cabaret and the Sondheim shows — e.g., a musical sequel to A Doll’s House titled A Doll’s Life (1982) — but were done in by inferior material, pretense, and the kind of directorial grandiosity and overkill that started to surface in the original Sweeney Todd and ran amok in Merrily.

None of that matters in the final accounting of Prince’s long life. Outside the business, no one really knows what a producer or director does, so in years to come no one will remember exactly what Prince did with Cabaret as a director or how, as a producer, he engaged Jerome Robbins to come in at the last minute, unbilled, to stage a new opening number (“Comedy Tonight”) for Forum when poor reviews and tiny audiences threatened to close the show after its Washington tryout. But the fact remains that there may be at most a half-dozen directors or producers in the American theater who can match his record — who have been collaborators on so many landmark works and who have been boosters of so many great theatrical artists at the start of their careers. The rewards for theatergoers now and in the future are incalculable. As his Cabaret was the best staging of a Broadway musical I ever saw, so his productions of Damn Yankees and Pajama Game were the first Broadway shows my parents took me to as a child. There are so many of us who never worked with or knew Harold Prince who owe a lifetime’s love of the theater to the heart-stopping shows that he made.