Is there anything more emotionally wrecking than the look of a grief-stricken baby lion, tears flooding down his furry cheeks, as he paws at the lolling head of his recently deceased father? Only, perhaps, the image of the aforementioned cub nestling his tiny body inside the hulking corpse of his dead dad.

Simultaneously simple and over-the-top, Mufasa’s death in Disney’s 1994 The Lion King stands out as one of the most brutal scenes in cinema. Never mind that it’s devoid of gore (no blood!) and part of a G-rated movie about cartoon cats, the tragedy ranks up there with the sight of Jack Dawson’s frosted arms detaching from the door-float as one of the most gutting onscreen moments. It was no surprise then, when the trailer for Jon Favreau’s remake of the animated classic debuted in November, that fans seized on the opportunity to self-analyze their still-affected psyches. “The lion king is really going to make me relive the trauma of my childhood that was mufasa’s death,” one fan tweeted. “I’m lowkey not ready to watch Mufasa die again though,” tweeted another.

Today, the people behind cartoon Mufasa’s death are relatively surprised by how culturally resonant their murder remains. According to several members of the original animation team — which spanned approximately 55 departments and 600 crew members, and produced over 1,000 scenes in total — they were initially divided on how audiences would react, with some thinking his death would push an already unusual concept — a Shakespearean lion musical with an Elton John soundtrack — into the realm of the unwatchable. But now that the scene has lodged itself into the limbic systems of so many, it’s fair to wonder if any remake, no matter the unprecedented amount of technology driving it, could rival the original’s ability to bring countless kids, parents, and at least one dog to tears.

“You get to a place — the uncanny valley — when you try to approach realism and you don’t quite get there,” says Daniel St. Pierre, head of layout on the original Lion King. “And the result is a little creepy.”

While the 1994 Lion King’s aesthetic never aspired to realism, its plot initially flirted with the idea. Back when they began the six-year process of creating Disney’s legendary lion saga, it wasn’t yet The Lion King — it was King of the Kalahari, slated to be “a naturalistic look at the life of lions in Africa,” recalls co-director Rob Minkoff. “Bambi with lions.” When he signed on to the project, Mufasa was similarly fated to die by a stampede, just not so brutally. It was Minkoff who helped spearhead the decision to render the death in excruciatingly minute detail — halfway through the movie, after the viewer had become invested in the character. The choice was somewhat groundbreaking, a tactic you’d expect from HBO, Minkoff says, not Disney.

“We needed to do the opposite of Bambi,” Minkoff adds. “We were trying to test the boundaries of what was possible in an animated movie, a family movie, a Disney movie.”

The team wasn’t just comparing itself to Bambi, by then 50 years old. Pocahontas was filming at around the same time, and Disney seemed to be placing its eggs in that basket. “We all thought we were the B-team. We were in crummy digs,” says artistic coordinator Randy Fullmer. “But we had self-belief, like the B-team does. We thought, We’ll show those guys.” With the stakes so high, the decision to end Mufasa was controversial among the crew, many of whom had young kids of their own. “I remember one animator who had little kids at the time who was traumatized by Bambi himself,” adds Fullmer. “He thought killing Mufasa was a horrible thing to do.”

But Minkoff remained steadfast. He brought new writers onto the story team — Joss Whedon and Billy Bob Thornton were both considered, though not selected. In a meeting, the story team realized that although The Lion King was not directly based on any source material, it did have echoes of Hamlet. This revelation, in part, compelled the team to go all-in on its disturbing death scene.

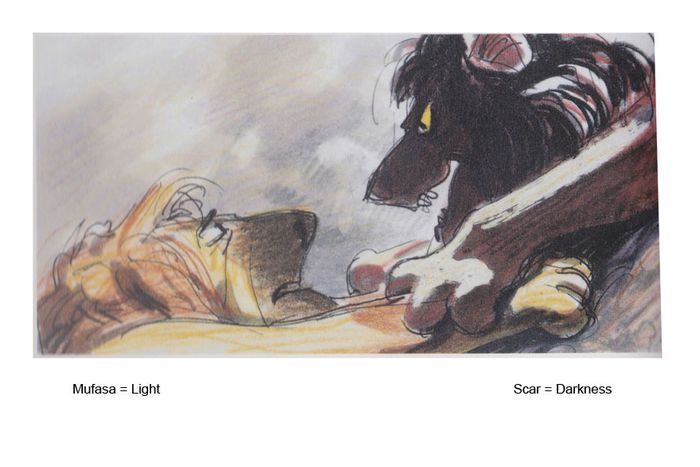

“You can introduce real drama and real human truths and still keep it appropriate for family viewing,” art director Andy Gaskill reiterates. “Death is a biological reality, a social reality. Once we accepted that, it started shaping the sequence in a different way.”

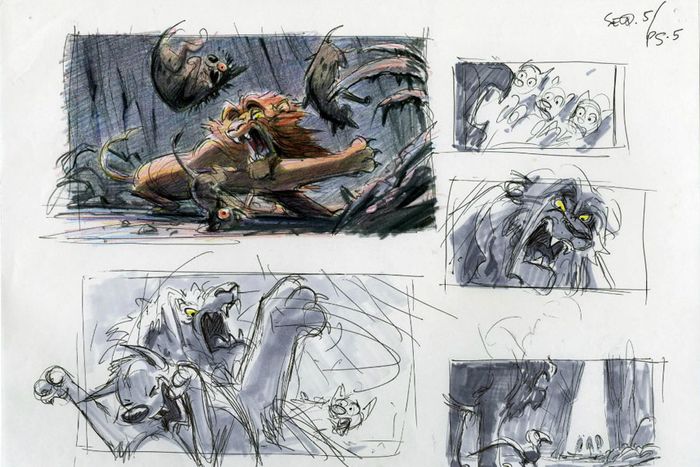

Though it’s only a couple of minutes long, Mufasa’s death scene took around 30 filmmakers weeks to create. First writers drafted the scene, then storyboard artists translated the words into comic-strip-like images; both underwent rounds of edits before approval. These images were combined with “scratch dialogue” to create outlines of the sequences. Then artists converted the storyboards into layouts, which were passed onto the animation team. Directors delegated different animators to design distinct parts of scenes — the foreground and background elements of set pieces, various characters. (Thirteen artists worked on Scar’s material alone.) They based their designs on dialogue recorded by the actors, producing thumbnails that also had to be approved. Completed black-and-white drawings were then sent to the cleanup department, before being shipped over to Computer Animation Production System (CAPS) to be digitally colored in. (For years, Disney kept its use of CAPS under wraps, with Pixar founder Alvy Ray Smith fearing “the magic will go away if people find out that computers are involved.”) The many images were finally compiled into single scenes. In total, the film contained about 1,300 of them.

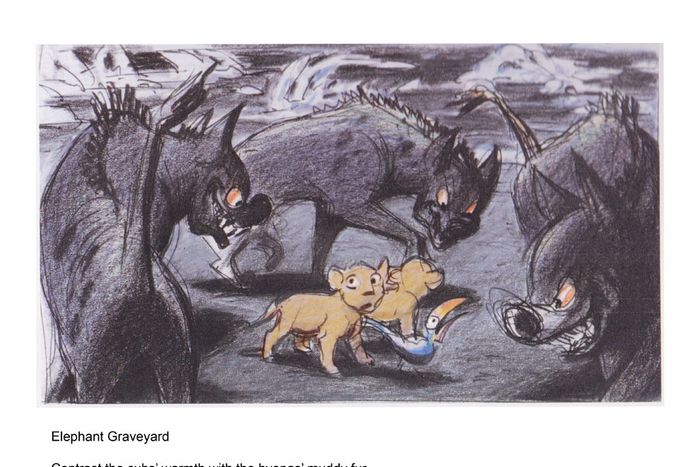

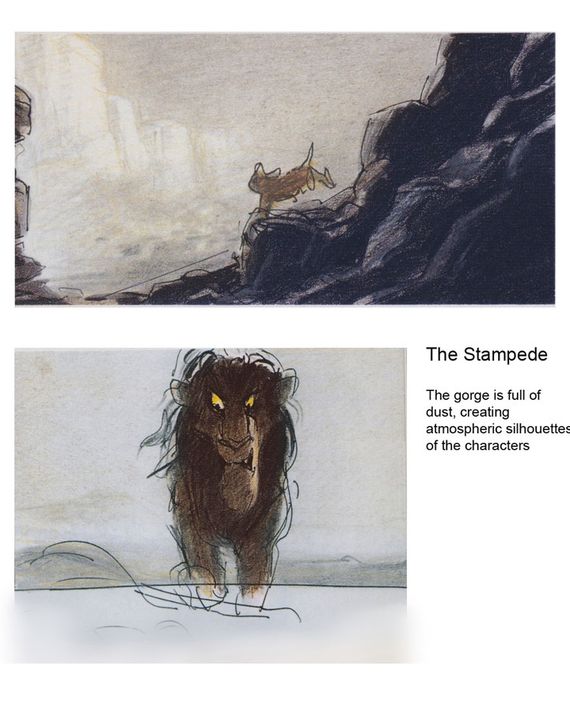

Mufasa’s death actually took place over the course of several scenes. They begin with Simba in a gorge, instructed by Scar to wait in the echoey passageway for a big surprise. (It’s “to die for,” the uncle purrs.) While Simba waits, hyenas whip a nearby throng of wildebeest into a frenzy, inciting a stampede in the cub’s direction. Scar runs to warn Mufasa that his son is in danger, knowing his brother will leap into the action. And he does. Mufasa saves Simba, just as the cub is thrown off a precariously placed tree branch, and stashes him on a cliff perch near the fracas before falling back into it. Ever the fighter, Mufasa manages once more to claw his way out of the throttling herd and up the rocks, where Scar is waiting for him.

Scott Santoro, who was in charge of The Lion King’s 2-D visual effects, oversaw all the scenes’ moving visual elements that weren’t characters. (He had a group of 50 people assigned to such tasks.) For the cliff scene with Scar, Santoro’s team choreographed the small rocks tumbling around Mufasa. “Rocks falling down a cliff may not seem significant, but they played into the overall emotional effect we wanted to achieve,” Santoro explains.

The rocks signal that the worst is about to happen: When Mufasa cries out for help, Scar smirks and digs his claws into his brother’s paws. Mufasa’s golden eyes inflate as he processes his fate. “Long live the king,” Scar snarls, his emerald irises ablaze with excitement as he thrusts his rival off the cliff, Mufasa’s robust shoulder blades rippling as he plummets, dead weight, into the stampede below. The haunting image fades to black.

The next frame zooms out from the black of Simba’s pupil. He’s watched the whole thing, but the viewers have to wait for the dust of the stampede to settle before they understand what’s happened. “The dust is all computer generated,” Gaskill says. “That created a level of reality. When you first see Mufasa again, you see this dark lump on the ground. Then his body is gradually revealed. You realize what’s happening as Simba does.” When Simba begins to cry, his tears leave a trail through the dust on his face. “We really focused on that one detail of the tear to capture what the scene was about,” Gaskill recalled.

What follows is that heartbreaking configuration of fallen father and mourning son: Simba nudging his dad’s lifeless head and wedging himself beneath Mufasa’s paw, cuddling up next to the corpse. Gaskill describes it as a “tableaux,” like “Greek statues in this murky dust.”

“We wanted Simba to deal with Mufasa’s dead body,” Minkoff says, “which was pretty strong stuff for a family movie, for any kind of movie really.”

The effect was chilling, for children and New York Times reviewers alike. “Scar arranges Mufasa’s disturbing on-screen death in a manner that both banishes Simba to the wilderness and raises questions about whether this film really warranted a G rating,” Janet Maslin wrote. Other critics, including Roger Ebert, fixated on the film’s visual prowess, which he attributed to the work of human hands and minds. “There has been a lot of talk recently about computerized animation, as if a computer program could somehow create a movie. Not so,” Ebert wrote. “Human animators are responsible for the remarkably convincing portrayals of Scar and the other major characters, who somehow combine human and animal body language.”

And yet a new Lion King hits theaters nationwide in July, replacing the hand-drawn 2-D effects of the original with a technologically unprecedented combination of virtual- and augmented-reality tools. Of course, humans are still very much involved in the process, their imprint is simply less perceptible to the viewer. The remake’s death scene is nearly a shot-for-shot tribute to the original, the photo-realistic lions moving from gorge to cliff to dusty tableaux. The effect is similarly tragic, but noticeably different than its emphatic cartoon predecessor. “Everything is laser-focused,” Minkoff describes, “minimalist” and “very concentrated.”

“It’s just a different world,” Santoro added. “There is a reason why people are still painting after the invention of photography. With animation, everything is simplified, caricatured, designed. That’s why children respond to it. They’d rather have an illustrated storybook than photographs because they respond to the pure colors, the designs. 2-D movies aren’t capturing reality; they’re creating an impression of reality.”

Today, some of the original Lion King animators worry that technologies like CGI will render the arduous process of hand-drawn animation obsolete. “The biggest tragedy is that people aren’t passing on this skill,” Santoro said. “In the future, it will be like bringing back tapestry making from the Middle Ages.” Maybe the only thing more distressing than Mufasa’s death is the impending death of the medium responsible for it.