The concept of white male violence — how it replicates and ripples through the world — is fertile ground for exploration, especially right now. Skin, written and directed by Academy Award winner Guy Nattiv, begins by juxtaposing such sickening violence, the kind fueled by right-wing ideology, with surprising grace. As the film progresses, however, the tactic only works by half measure, as so much of the roots of brutality are left unexplored or pushed to the margins in order to tell what is essentially a well-worn tale of a dangerous man beset by his own demons, set on the right path thanks to the love of a good woman who has to constantly redraw her boundaries in his presence. In this case, the man is a neo-Nazi, played with volcanic intensity by Jamie Bell.

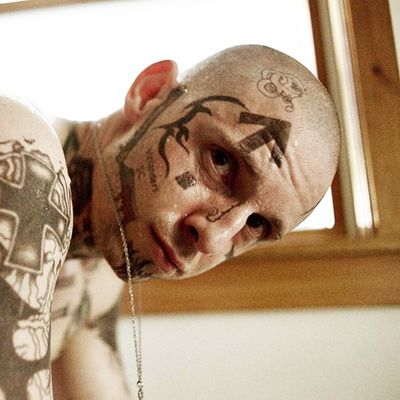

Bryon “Babs” Widner (Bell) is the kind of man who builds up muscle like a suit of armor he wears against the world. The only affection he shows regularly is toward his Rottweiler, Boss. Heavily tattooed, his face a mask of anger, he cuts a path through life with violence — whether that be when he brutally beats a young black boy during a riot or defends a trio of young girls getting heckled at a right-wing rally. It’s this last gesture that is meant to endear us to Babs, particularly when he embarks on a tender relationship with their mother, Julie Price (a magnetic Danielle MacDonald), a young woman trying to extricate herself from the neo-Nazi movement she was born into — the same one maintaining a stranglehold on Babs.

The dilemma Babs faces, which is based on a true story that already sparked a separate documentary, is driven by two emotions: the love he feels for Julie and the hate that’s gripped him for so long. Early in their courtship, between beer and intense kisses, Julie asks Babs how he fell into his right-wing gang of criminals, who burn mosques and spit in the faces of black people on the street. We learn of his tempestuous childhood — marked by alcoholic parents and neglect — which made him a prime target for neo-Nazi leader Fred “Hammer” Krager (Bill Camp) and his wife, Shareen (Vera Farmiga). What comes into focus is that Babs traded one abusive dynamic for another. Fred and Shareen gave him food and shelter when he was homeless and lost, exploiting his vulnerability as a bedrock for hate. Fred taught his underling to value masculinity as a weapon against the world, while Shareen granted a love, barbed and ephemeral as it was, that Babs had never encountered.

This is where Nattiv and his collaborators shine, mining what’s lost as Babs drifts further away from the movement at Julie’s urging. Interspersed throughout the film are flash-forwards to Babs’s tattoo-removal procedure. The extreme close-ups and sound design highlight his cries of pain, more than suggesting that the horror of navigating away from his former life isn’t just emotional, but a physical burden. One of the best scenes in the film comes later on, though, when Babs has fully committed to Julie and the new, sensitively sketched family he is calling his own. He comes home to find Fred, Shareen, and more neo-Nazis populating the abode, panic seizing Julie’s face. What follows is prime family drama: loyalty tested, old wounds prodded. The complications behind Babs’s glacial drift from his former life rear forward.

Farmiga’s singsong sweet voice is the perfect cover for Shareen’s brand of manipulation, and Bell’s commitment to the physical embodiment of anger kept me transfixed. But there’s another figure who haunted me: Daryle Jenkins (Mike Colter), an anti-racist activist who has made it his life’s mission to help neo-Nazis transition toward better, more productive lives. Daryle is a thinly drawn angel on Babs’s shoulder, absorbing abuse and always responding with forgiveness. Unfortunately, the relationship between the two is never fully drawn, and what could have provided a window into the process of making amends, particularly with the communities of color that Babs terrorized, falls victim to Nattiv’s more substantial interest in the explosive relationship Babs has with Julie. By never allowing Daryl’s character to develop alongside Babs, we miss the opportunity to see what the complicated work of unlearning racist rhetoric even looks like.

Ultimately, Skin — despite its artful compositions and meditative editing choices — devolves into a reductive redemption fable that doesn’t fully wrestle with the racism or politics governing Babs’s decisions. Certain aspects of the neo-Nazi movement are explored (the rituals, the shared hatred), but there is just as much left unaddressed. What is it about the ideology itself that captured Babs? It ends on a note of forgiveness for Babs but it is one that feels unearned. Time again we watch as the idyllic life Babs is trying to form with Julie explodes, and we see the apologies that follow, but we miss the daily work, the gradual change that would compel her to draw him back in despite the danger he poses to her children. The failure of the film to fully grapple with how Babs’s anger pulses through the lives of the women in his orbit undercuts the tremendous work that Bell accomplishes onscreen.