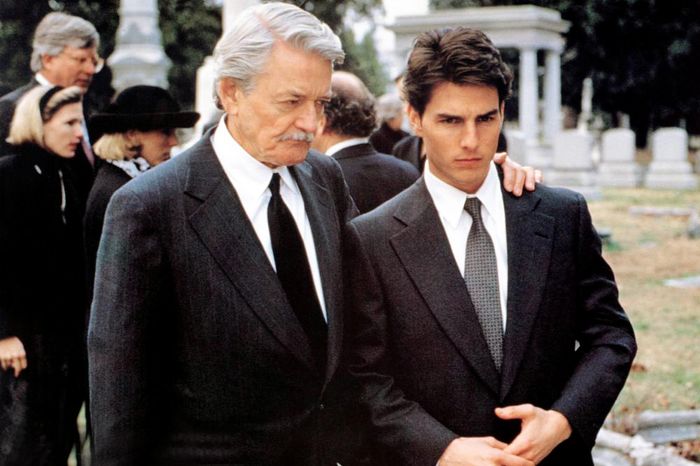

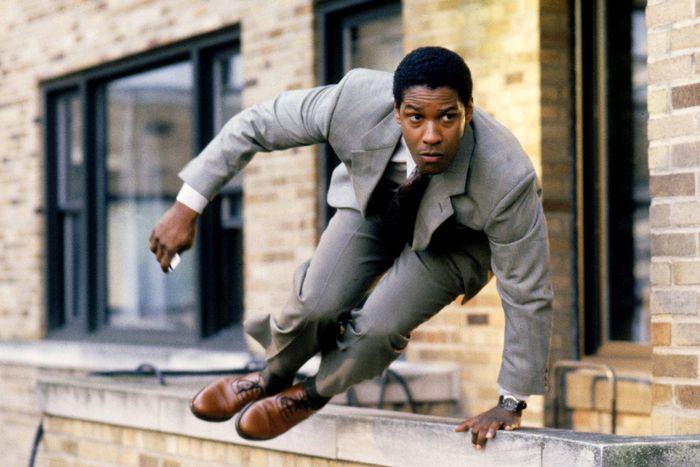

Twenty-five years ago, Hollywood was enjoying a pipeline to success as clean and unobstructed as any. The paperback legal thrillers of author John Grisham featured in supermarkets across the nation, and starting with The Firm in 1993, were taking over movie theaters, too. The cinematic versions arrived with impeccable casts and big-name directors, all raking in over $200 million at the box office (when adjusted for inflation). Sydney Pollack helmed The Firm, starring Tom Cruise, Gene Hackman, and an Oscar-nominated Holly Hunter. That same year, Alan J. Pakula directed The Pelican Brief, with Julia Roberts and Denzel Washington. Joel Schumacher would end up making Grisham’s debut novel A Time to Kill with Samuel L. Jackson, Sandra Bullock, and a breakthrough actor named Matthew McConaughey. But first he’d direct Susan Sarandon to a surprise Oscar nomination in 1994’s The Client.

With its incredibly simple yet compelling premise — a kid on the run from the Mob avails himself of the legal services of a self-made Memphis lawyer who works outside the system to get justice — The Client may well be the quintessential ’90s Grisham thriller, a genre that’s been seemingly lost to history despite the echoes it continues to have in the careers of the films’ stars. Think about how Jackson’s “YES, they deserved to die, and I hope they burn in hell!” line in A Time to Kill became a part of the Sam Jackson persona. Think about how The Firm came to define Tom Cruise’s precision-running era, or how The Pelican Brief perfected the parking-garage chase scene. In the mid-1990s, the legal thriller was every bit as legitimate a genre as the romantic comedy or the Die Hard–in–various–strange–settings action thriller: 1994 saw three legal/political thrillers in the box-office top 15 (The Client, Clear and Present Danger, and Disclosure); 1993 had three as well (The Firm, The Pelican Brief, and Philadelphia), and 1992 produced two (A Few Good Men and Patriot Games). The last time a legal thriller reached the box-office top 15? Erin Brockovich in 2000 (unless you feel like counting 2012’s Lincoln, which I do not).

It’s a familiar refrain, but today, the box office is dominated by Marvel superhero movies, Disney remakes, and animated sequels, a trend that doesn’t seem to be losing steam anytime soon. Beyond the theater, Netflix has begun to pick up the slack on certain forgotten genres — last year represented a confident step toward bringing the rom-com “back.” But the poor legal thriller remains untended. Which is why I am likely one of the few individuals to have acknowledged the 25th anniversary of The Client (today!), the dialogue of which has remained firmly embedded in my brain since I was a teenager first discovering it.

As a bookish indoor kid who hadn’t figured out his sexuality, I was a firm supporter of the middlebrow legal thriller. I eschewed bike riding, kissing girls (uh, see above), and learning how to smoke cigarettes for the clearcut satisfaction of a well-executed courtroom monologue, or Julia Roberts cryptically intoning that everybody she’s told about the brief is dead. The characteristics of the middlebrow legal thriller dovetailed so well with the tastes of a teen who imagined himself to be quite smart and sophisticated — they didn’t so much require a familiarity with the law but with the three or four legal concepts that particular film decided were important. In The Firm, the concept was “billable hours.” In A Time to Kill, it’s “change of venue.” Once you’ve got the concept down, the movies tend to be about chase scenes and tense cross-examinations. With Grisham, the Mob is very often involved, or else the government acting like the Mob. By the end, the two characters we care most about arrive at an understanding about each other. It ain’t Tolstoy, but it is deeply enjoyable.

The Client was easily the most teen-friendly of Grisham’s books because it had a teen protagonist: Young Mark Sway (played in the film by the late Brad Renfro) and his little brother, Ricky, are out wandering where they’re not supposed to and end up witnessing the suicide of a Mob lawyer who, before he offs himself, spills some secrets to the boys about where certain bodies are buried. The shock of the suicide sends Ricky into a catatonic state, and once word gets out that the boys were witnesses, the state — in the form of vainglorious prosecutor “Reverend” Roy Foltrigg (Tommy Lee Jones) — and the Mob come down on him. Mark ends up turning to a down-on-her-luck, and thus affordable, lawyer named Reggie Love (Susan Sarandon). Reggie’s scrappy lawyering and motherly affection for Mark are a potent combination, especially from Sarandon, who is at the peak of her powers in the early ’90s. She’s coming off back-to-back Oscar nominations in 1991 and 1992 for Thelma & Louise and Lorenzo’s Oil, earning a reputation as the best working actress to have never won an Oscar.

Joel Schumacher was chosen to helm the endeavor. His career is dotted with disasters like The Phantom of the Opera and the Jim Carrey numerology dud The Number 23. He’s the man who put nipples on the Bat-suit for Batman & Robin. But in focusing on the Bat-nips, we forget that he also made Batman Forever, a candy-colored comic-book extravaganza that was second only to Toy Story at the 1995 box office. We forget he made indelible cult classics like The Lost Boys and strange, daring character-based thrillers like Falling Down and Phone Booth. The Client might be Schumacher’s most purely entertaining film, as Renfro’s character gets into and out of scrapes with the kind of rude verve you’d expect from a real little shit of a kid. The film is also a perfect example of its genre; the legal maneuverings are engrossing enough but just this side of absurd, no better example of which is when Mark comes up with the idea to assert his Fifth Amendment right not to testify on the fly, while he’s on the witness stand, without any prior legal knowledge. Kids!

The Client’s supporting cast is dense with familiar faces: Anthony LaPaglia, William H. Macy, the late J.T. Walsh, and Bradley Whitford and Mary Louise Parker (years before they would play tempestuous lovers–D.C. operators on The West Wing). But the real gem at the heart of this movie is Susan Sarandon, who milks her star turn for all its worth. Her scenes opposite Tommy Lee Jones as they face off over the fate of this young boy are the kind of crackling movie-star showdowns that rarely appear outside the action drama. Whether she’s sliding through a legal loophole, casting a maternal glance Mark’s way, or nervously lighting a cigarette in a way that only 1994 cigarettes could be lit (between Pulp Fiction, Reality Bites, and this movie, it was a banner year for smoking), Sarandon is cresting on the charm and capability that defined her remarkable early-’90s run, a run that kicks off roughly around 1988’s Bull Durham and ends definitively with her Oscar win for 1995’s Dead Man Walking. That Oscar win was perceived universally as an acknowledgment that it was “her time” in that classic way Academy Award victories are hardly ever just about the performance in question.

Sarandon’s Oscar nomination for The Client, however, was perceived to be a fairly ridiculous reach by the Academy. The role was a crowd-pleasing turn in a summer potboiler, sure, but nothing approaching the tony theatrics of Jodie Foster in Nell or Jessica Lange (who ultimately won that year) in Blue Sky. Oscar observers received Sarandon’s nomination with all the begrudgment of a late-stage Meryl Streep Florence Foster Jenkins nod. Yet looking back on the performance 25 years later, this dismissive attitude feels … off. Sarandon’s Reggie Love is the kind of movie-star move that was easy to take for granted in the ’90s, when actors regularly carried $100 million films on their backs. Now, in the age of franchise characters and intellectual property, a lead performance like Sarandon’s in The Client feels far more valuable.

Susan Sarandon’s trajectory makes me think of Amy Adams, the six-time Oscar nominee whose Academy Award win seems forever just beyond the horizon. It’s fascinating that, with all those nods, Adams has yet to arrive at “her time.” Just last year, Adams was nominated for Vice, a polarizing movie but a Best Picture nominee nevertheless. She lost to Regina King for the unnominated If Beale Street Could Talk. King’s performance was more acclaimed, but Oscar history is littered with acclaimed performers losing out to individuals with more “career momentum.” That kind of momentum is what propelled Sarandon to her win for Dead Man Walking, ahead of critical faves like Elisabeth Shue (Leaving Las Vegas). That kind of career momentum is harder to come by when Hollywood is making movies for superheroes and cartoons and little else. The two most recent examples of such a phenomenon were Meryl Streep (for The Iron Lady in 2011) and Sandra Bullock. When Bullock won her Oscar in 2009, it wasn’t just for the performance she put onscreen in The Blind Side that earned her the statue. It was a career spent making movies that mainstream audiences saw and loved and remembered.

An actress like Amy Adams, whose career kicked off with 2005’s Junebug, doesn’t get to make movies like The Client. She divides herself between small, thankless roles in superhero movies (you’d be forgiven if you forgot that she plays Lois Lane in the DC cinematic universe) and indie–Oscar-bait fare, some of which penetrate the mainstream (look, somebody put $150 million worth of box-office receipts into American Hustle) and some of which does not (like Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master). If only there were middle-ground legal thrillers or romantic comedies through which Amy Adams could endear herself to the movie-going public the way Sarandon did with The Client or Sandra Bullock did throughout the ’90s in movies like While You Were Sleeping (and the aforementioned A Time to Kill).

Losing that middle class of movies — not indie, not Avengers — means losing a lot of what is interesting to the layperson about so-called Oscar narratives. Every year it seems that ABC and the Academy wring their hands over how to get ordinary viewers invested in the Oscars. They try to shorten the ceremony, add categories to please the action-blockbuster crowd, add (or subtract) musical performances. Maybe part of the problem is that by squeezing out mid-budget dramas, rom-coms, and legal thrillers, you take away the home audience’s ability to follow a movie star’s career trajectory on its way to Oscar. Maybe if Amy Adams had been able to star in movies like The Client and Bull Durham, her momentum toward an eventual win would feel like a more compelling story for everybody, not just hard-core cinephiles and Oscar nerds (hello!).