In 1994, Stanley Kubrick sent the screenwriter Frederic Raphael a novella about a doctor who embarks on a dark odyssey of the soul after learning that his wife has fantasized about fucking another man. The story took place in Hapsburg Vienna; Kubrick wanted to know if Raphael could adapt it into a screenplay set in contemporary New York. As Raphael later recalled in an essay for The New Yorker, he was initially skeptical. “Hadn’t many things changed since 1900,” he recalled asking Kubrick, “not least the relations between men and women?” “Think so?” Kubrick replied. “I don’t think so.” Raphael thought about it. Then he said, “Neither do I.”

The film they eventually collaborated on, Eyes Wide Shut, came out twenty years ago to mixed reviews. While some critics praised it as one of the master’s greatest works, it was perceived by some as a disappointment, an underwhelming valediction from the great director, who died a few months before its release. One of the most consistent complaints about it was that its attitude toward sex seemed badly dated. “It feels creaky, ancient, hopelessly out of touch, infatuated with the hot taboos of his youth and unable to connect with that twisty thing contemporary sexuality has become,” wrote Stephen Hunter in the Washington Post. Rod Dreher of the New York Post quipped that it seemed to have been made by “someone who hadn’t left the house in 30 years.” Relations between men and women, in other words, had in fact changed a lot.

But had they really? I’ve watched the movie close to a hundred times in the last two years and I’m here to tell you that it was timely then, it’s timely now, and as sad as it is to say this about the world, it may well be timely forever.

My Eyes Wide Shut addiction first took hold in the spring of 2016. I was working on a novel and rarely left my apartment. The book that I was writing was a sort of fairytale, and so was the film. With its dreamy music and strangely mannered dialogue, its Christmas lights twinkling in scene after scene, it would fast track me into a trancelike state of creativity, detaching me from the real world and its mundane concerns.

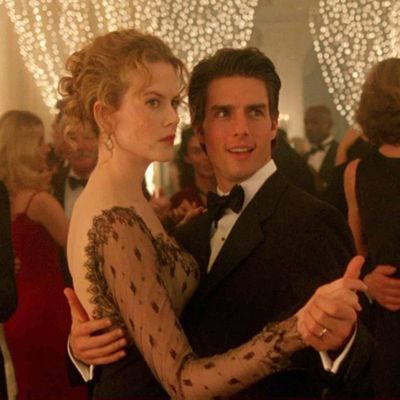

What critics saw as dated, I saw as timeless. Though it technically takes place in 1990s New York, the film keeps one boot planted firmly in the fin de siècle world of Arthur Schnitzler’s novella. The opening credits are set to a waltz; the gentleman who hits on Nicole Kidman’s character in the following scene is an elegant Hungarian; the film’s iconic centerpiece, a masked ritual that turns into an orgy, seems like the sort of affair that might have titillated Gustav Klimt. And then there’s Tom Cruise’s character, the amazingly naïve Dr. Bill Harford. Early on, when his wife suggests that his patients are horny for him, he assures her that women “don’t think like that” — as if he would know better than her. She falls to her knees laughing, then reveals that she was once so taken with a hot sailor that she fantasized about giving up their marriage (and even their daughter) for a single night with the guy.

It’s this confession that serves as the movie’s inciting incident, sending the shocked doctor reeling out of the apartment, out into the wild New York night. And to critics, that registered as bizarrely unrealistic. It was the ’90s after all — the decade of Wild Things and Cruel Intentions, of Sharon Stone’s Catherine Trammel asking Michael Douglas’s Nick Curran, “Have you ever fucked on cocaine, Nick? It’s nice.” The President was getting head in the Oval Office. Could any man really be as innocent as Dr. Harford?

Well, yes.

In the fall of 2017, a month or so after the world learned that an ogre in a tuxedo had been preying on Hollywood’s women for decades and getting away with it, I resumed my daily viewings. By then, #MeToo was in full swing, and a lot of men had been named. Like other women I know, I was overwhelmed, not by the fact that there were so many bad men out there — that was to be expected. It was the “him too?” of it all — the fact that so many of the men I knew were so shocked by the revelations.

I knew that Dr. Harford would be shocked, too. Here was a man so oblivious to his own wife’s sexual desires that he couldn’t abide the thought of her merely fantasizing about someone else. He’s totally clueless about what it’s like to be a woman, and when his wife tries to school him, he runs away in fear. Dr. Harford’s ignorance of his wife’s desires and the guys I knew who couldn’t seem to wrap their minds around the avalanche of stories of abuse struck me as two sides of the same coin. Both attitudes stemmed from an inability to understand the interior life of women and a refusal to acknowledge that we might be experiencing sexual thoughts and feelings so foreign to their own. And so when guys told me that they couldn’t believe the stories that were coming out about the powerful men who were being named, I heard them saying that they had chosen to be clueless, too. Was it because they were afraid of what might happen if they’d kept their eyes wide open? Afraid they’d have to be friends with different people, look up to different men, maybe even challenge those in power over them, lest they accept their complicity in a structure they knew to be abusive?

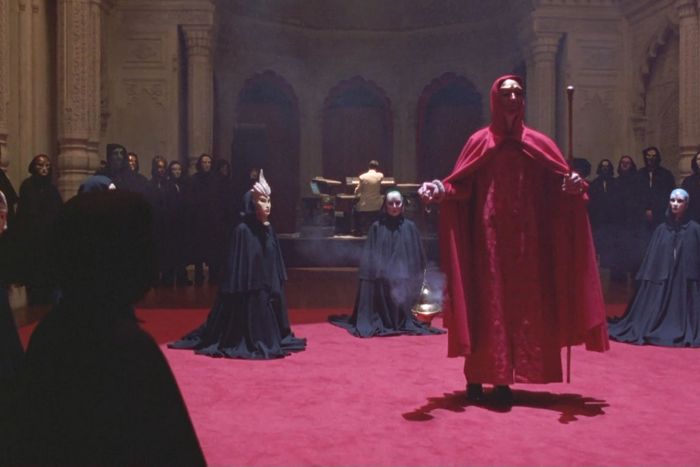

Complicity is what Harford seeks: He’s desperate to be on the inside. At the height of the film, he infiltrates a secret society where powerful men in masks and robes are having ritualistic sex with subservient naked women. Who are these women, and why are they there? They have supermodel bodies, and we can infer that they’ve been hired to do a job. But that’s about all we know. At one point, Harford asks one of them to remove her mask; she refuses, and begs him to leave the party, warning him that if he stays, it could cost him his life. A moment later, he’s exposed as an intruder, and a sort of tribunal is convened to decide what to do with him. As his fate hangs in the balance, the woman he met earlier intervenes, crying out, “Take me instead!”

Later, her body turns up in the morgue. Dr. Harford suspects that she was murdered as punishment for trying to help him, but he doesn’t go to the police. Instead, he allows himself to be lulled into a state of complacency by one of the men who was at the party, a master-of-the-universe type played by Sydney Pollack. Pollack reads Dr. Harford perfectly, accusing him of “jerking himself off” to the thought of the woman sacrificing her life for his. The truth, he insists, isn’t nearly so romantic. “She was a junkie! She OD’d!” As Pollack circles the room, tapping a pool cue in a faint echo of the ritual at the masked ball, he urges the doctor to let it go. The men at the party were “not just ordinary people,” he warns. “If I told you their names […] I don’t think you’d sleep so well.” Harford doesn’t press him for those names or any other details. He doesn’t want to know. Although Harford spent the day leading up to this conversation retracing his steps, desperate for answers, Pollock easily convinces him to give up and go home. That’s how power triumphs — Pollack offers the smallest crumbs of an explanation, drawing him into the conspiracy while offering no real answers, and Harford accepts the bargain.

If all this felt dated back in 1999, maybe that’s because we weren’t quite as savvy as we thought. We’d spent the past year obsessing over the semen stain on Monica Lewinsky’s dress, but we’d somehow missed the point of the whole dark saga. We thought it was a story about sex, but it was really about power — about the abuse of it, and our complicity in that abuse. The world’s most powerful man walked away from a scandal unscathed while his intern’s life was torn apart and we shrugged at her ordeal. We were all Dr. Harford. And by that light, Eyes Wide Shut doesn’t seem quaint; it seems prescient.

At the very end of the film, Dr. Harford comes home to find the mask he’d worn at the party resting on his pillow beside his sleeping wife. He breaks down in tears and promises to tell her everything — but the confession, which we never hear, doesn’t seem to bring them happiness. In the next and last scene, Nicole Kidman’s character suggests that the moral of the story is that they should be grateful for what they have. And what do they have? A domestic partnership built on her husband’s ignorance of her desires. She, too, is choosing complacency. Her marriage depends on it. And that’s Kubrick’s point. As long as men choose ignorance, and women accept it, the relations between them will never change. Kubrick, the most controlling and precise of directors, knew exactly what he was doing. He didn’t make a naïve film — he made a film about naïvete, and the toll it takes on the world.