In Mindhunter season two, David Fincher and his collaborators dig deep into one of the most infamous crimes in American history, a wave of killings that would become known as the Atlanta child murders. From July 1979 to May 1981, at least 28 people in the Atlanta area, most of them impoverished black boys and teenagers, were kidnapped and murdered. The writers of Mindhunter use this infamous case in their semi-fictional narrative, although they do stick closely to many of the facts, including the real names of the victims and their families, as well as the controversial suspect at the center of it all, Wayne Williams. So, what’s the true story behind the Atlanta child murders? Let’s break down the facts and fiction of the case, including the details that Mindhunter doesn’t cover and why Atlanta police reopened the investigation earlier this year.

The Victims

The killing spree began in the summer of 1979 when 14-year-old Edward Hope Smith and 13-year-old Alfred Evans disappeared. The bodies of both boys were found in a vacant parking lot days later, although Evans wouldn’t be identified for more than a year. In a sign of problems to come, the discovery of their bodies didn’t prompt immediate panic: “Police wrote off the killings as drug-related and almost forgot them,” the Washington Post later reported. Even when Milton Harvey, age 14, and Yusuf Bell, age 9, were both found dead in late 1979 — Bell’s body was discovered in an abandoned school, a mere four blocks from his home — Atlanta police had yet to link all the disappearances and murders together.

In 1980, the death toll intensified. Twelve-year-old Angel Lenair was murdered in early March; before her body was found tied to a tree, per the Post report, police insisted to her mother that the girl had simply run away from home. Eleven-year-old Jeffrey Mathis disappeared next, although his body wouldn’t be found until almost a year later. Eric Middlebrooks, age 15, was found bludgeoned in May. That same month, Camille Bell (mother of Yusuf), Willie May Mathis (mother of Jeffrey), and Venus Taylor (mother of Angel) organized the first meeting of the Committee to Stop Children’s Murders, a group that pressured the police to seriously investigate a connection between the cases. But the disappearances kept mounting: 7-year old Latonya Wilson and 10-year-old Aaron Wyche in June, 9-year-old Anthony Carter and 10-year-old Earl Lee Terrell in July. Five more children vanished before the year’s end; seven other children and six adults were killed in 1981. The bodies of some victims were found shortly after their disappearances, while others didn’t surface for months. Some of the victims knew each other and, as depicted on Mindhunter, lived only a few houses apart.

The Investigation

The early police work into the Atlanta child murders could politely be called incompetent. For months, investigators refused to believe that the killings were even connected, and public figures hesitated to make details of the case known for fear of how it might damage the city’s reputation.

Mindhunter drops its semi-fictional characters into the case by way of the grieving mothers behind the Committee to Stop Children’s Murders. The fictional Holden Ford meets Camille Bell, played in the show by June Carryl, in a story line that captures how she and other mothers pressured the police to face the facts of what was happening in their city. Atlanta police had formed a task force with other state investigators by that time, with two FBI agents acting as a liaison between local officials and the Behavioral Science Unit, but a federal case had yet to be opened. As the real Bell told People back in 1980, “The more we talked, we found that none of us had been able to get the police to keep in touch with us. They wouldn’t call us back; nothing was being done.”

The investigation finally started to get serious in August, after 13-year-old Clifford Jones’s body was found strangled. The fact that Jones was from another city — he was from Cleveland and visiting relatives — likely helped turn up the heat and bring national attention to the case. After 11-year-old Darren Glass went missing in September, his disappearance led the FBI to open a kidnapping investigation, according to former FBI official Susan Lloyd, based on the theory that the boy was taken across state lines. By November, the FBI opened an investigation known as “ATKID” and the nightly news was regularly reporting on the case. A six-figure reward was raised to help capture the killer. Thousands of people started to help with the investigation.

To be clear, Mindhunter plays a bit loose with history here. Holden Ford is on the ground a lot in Atlanta, meeting the grieving mothers and guiding the investigation. Atlanta authorities really did call in the FBI, and bureau agents indeed helped profile the suspect and even visited three crime scenes. According to Lloyd, Ford’s real-life inspiration, John Douglas, came down to Atlanta in early 1981: “Douglas walked the woods in south Atlanta, where five of the children’s bodies had been found, and reviewed the case files. He also relied on assessments from interviews previously conducted by his unit with 25 serial and mass murderers.” But he wasn’t the first FBI profiler from the Behavioral Sciences Unit to work on the case, and his approach differs somewhat from the much more on-the-ground work portrayed in Mindhunter. Much like Ford, though, Douglas did believe that the killer was a black person, because, as Lloyd recounts, “a white person could not easily travel in black neighborhoods without creating a great deal of suspicion.”

On Mindhunter, Ford’s profile drives the investigation, with the show questioning whether or not it solved the case or pinned the murders on the wrong man. The show puts Ford way more on the ground and hands-on than Douglas was in real life, but the fictional addition serves an important thematic purpose: It emphasizes how profiling tremendously influenced the case, while also showing the heavy involvement of the FBI over the final months of the investigation.

The Suspect

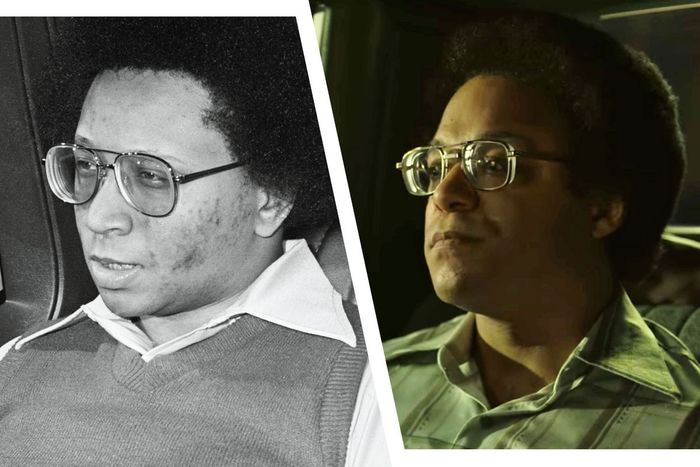

In late 1980, a shift in the killer’s M.O. led to a major break. The bodies of victims, which until that point were found on dry land, began turning up along nearby rivers; FBI profilers believed that the killer hoped to wash away evidence, after an Atlanta paper reported that investigators found carpet fibers and dog hair on many victims’ bodies. FBI Special Agent Mike McComas first proposed canvassing bridges along the rivers, which led to stakeouts of a dozen bridges in the area. As captured on Mindhunter, one of these stakeouts led investigators to Wayne Williams, who was pulled over after Atlanta police officers heard a loud splash in the Chattahoochee River on the early morning of May 22.

The 23-year-old Williams, whose station wagon investigators spotted on the bridge shortly after hearing the splash, denied any involvement in the case, claiming that he was a talent scout trying to find a singer named Cheryl Johnson, whose existence could never be verified. Two days later, the asphyxiated body of 27-year-old Nathaniel Cater was found near the spot where Williams was pulled over; in June, the police linked green fibers found in his house to another of the murders. As detailed on Mindhunter, Williams really was a music promoter trying to find “the next Michael Jackson,” meaning he would have perhaps come in contact with boys in the age group of the victims. On June 21, he was arrested for the murders of Cater and 22-year-old Jimmy Ray Payne.

Did the FBI just find someone who fit Douglas’s profile, or did they actually catch the right man? Douglas himself added to the fuel to the debate in the days after Williams’s arrest, telling the press that Williams “looks pretty good for a good percentage of the murders.” (As Douglas recounts in his Mindhunter book, he was later censured by the FBI for this statement.) This theory quickly caught fire, with the Atlanta Constitution running a story with the headline, “FBI Man: Williams May Have Slain Many”.

Williams denied any connection to any of the murders, maintaining his innocence through a closely watched trial that began in January 1982. Prosecutors built their case around “a large number of fibers from the Williams’ home and car including fibers from the trilobal yellowish-green carpet, a bedspread and yellow blanket from Williams’ bedroom, and dog hairs from the family’s mixed breed German shepherd,” Lloyd writes. “Nineteen different sources of fibers and hairs were matched to fibers on a number of victims.” However, despite presenting evidence from the other killings, Williams was only charged with the murders of Cater and Payne. The trial ended with a conviction on February 27; Williams was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences. Soon after, investigators attributed to Williams the vast majority of the unsolved murders. But the controversy was just beginning.

The Reopened Case

In the decades since the trial, the belief that Williams wasn’t responsible for all of the Atlanta child murders has grown substantially, with even some relatives of the victims professing his innocence. The sense that Holden Ford may have helped convict Williams simply because of how much he fit a profile is palpable in the closing scenes of Mindhunter season two, leaving viewers to question exactly what happened and whether the investigation went wrong. The theme of doubt is woven throughout the season: the doubt Bill Tench has in his son, the doubt about the culpability of people like Tex Watson and Elmer Wayne Henley, and the doubt that the Atlanta case was really solved. If the first season of Mindhunter was about striving for certainty, the second is about how often that remains out of reach.

No suspect has ever been charged for any of the Atlanta child murders — Cater and Payne were both adults — and Williams remains in prison to this day. Five of the cases were officially reopened in 2005, including the death of Aaron Wyche, although those investigations were reportedly dropped again in 2006. CNN ran a documentary in 2010 that included an interview with Williams, who continues to maintain his innocence.

Last March, Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms and Atlanta police chief Erika Shields announced that state and local officials will retest evidence in the case. They’re even looking into other cases from the era that could be related: According to the New York Times, investigators are reviewing a 15-year-window, from 1970 to 1985, during which 157 children were murdered, including the previously known victims in the case.

Notably, Douglas himself doesn’t think that Williams committed all of the crimes. In 1995, he wrote in his Mindhunter book, “Despite what his detractors and accusers maintain, I believe there is no strong evidence linking him to all or even most of the deaths and disappearances of children in that city between 1979 and 1981. Young black and white children continue to die mysteriously in Atlanta.”

One of the most chilling scenes in Mindhunter season two happens when a police officer, played by Brent Sexton, suggests that other criminals may also be killing young black boys because they know the murders will get caught up in Ford’s vision of a single perpetrator. (In 1985, Spin magazine ran a piece suggesting that the Klu Klux Klan was behind several of the murders and that authorities knew this and covered it up.) What if Wayne Williams was merely the scapegoat for someone else? Did the FBI profilers solve the Atlanta child murders, or did they help deny justice for dozens of grieving parents? We may never know.