Somewhere along the way, I couldn’t tell you exactly when, my dancer friends and I started praying to Stripper Jesus. Stripper Jesus, a pastiche of the real Son of God and a mythic, divine female-affirming presence, is the one we appeal to when we need the spiritual big guns to protect us from a stalker, to help us draw big tips, to land a straight job, or to clear the appointment book at the busy nail salon when we desperately need a fill. Trust that I sat in the theater praying to Stripper Jesus that Hustlers not be yet another strip-club turkey. I was dancing during the days of Showgirls and Striptease, which left me in a state of permanent cringe. Like every other dancer, I’m exhausted by strippers being diminished within the stingy aperture of the male gaze, remanded to the role of ditz, set dressing, DSM textbook case, or murder victim. When it comes to Hollywood depictions of strippers, we are used to feeling betrayed.

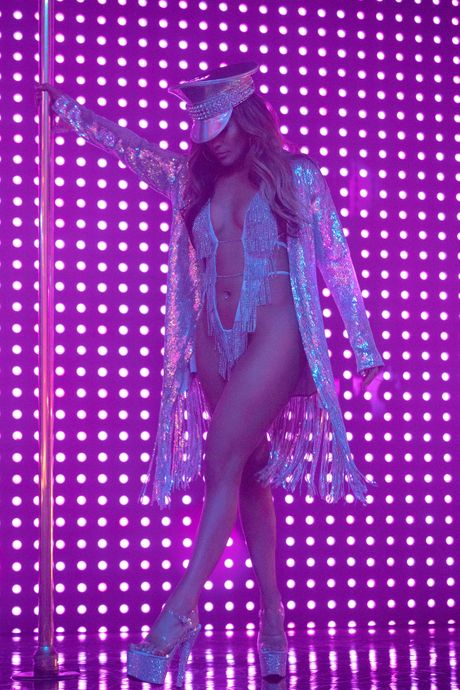

And so I’m pleased to report — all praise, Stripper Jesus — that my prayers were answered with this movie, and then some. The gonzo story line of strippers turning the tables on their pigheaded customers by drugging and robbing them, based on Jessica Pressler’s 2015 exposé, “The Hustlers at Scores,” is by turns hypnotic, unsettling, and addictive. Tales of scrappy heroines on the job have been told before in Flashdance, Working Girl, 9 to 5, and Pretty Woman, but Hustlers is the first one to effectively tip a hat to the specific travail of stripping. I not only enjoyed the authentic touches — the acrylic French tips, the Bebe separates, Ramona’s at-home tanning bed — I respected the hell out of it. I’m not saying the movie made me feel comfortable, but it did make me feel recognized.

There’s something of a stripper omertà at work among dancers — we don’t like to talk about our job with civilians very much. Even as a writer who has addressed my dancing days before, and who feels somewhat emboldened by the sympathetic tone of the movie, I tread very, very carefully. For good reason. In a highly stigmatized profession, anything you say can and will be used against you. And so I fully understand why Cardi B choked up in talking about her reaction to the film — I shed more than a few bittersweet tears of reminiscence myself.

As a high-school dropout with severe undiagnosed depression, I turned to stripping for the same reason as Destiny — in dire straits, it seemed like the best bad choice (and like Destiny, I’d been bounced out of low-wage, high-tedium retail). Once I began working, I realized the club could be both a playful pantomime of old-school heteronormative gender roles and a grisly battle-of-the-sexes triage scene. Predicting which scenario would greet me on a given shift was impossible. For such scenes in Hustlers, Jacqueline Frances, a savvy and sunny stripper with whom I’m lucky to be acquainted, was hired not just to consult on stripper verisimilitude but to keep the dancer extras comfortable re-creating the chaotic environment. This commitment to care brought to the fore years’ worth of sublimated injury and unprocessed rejection. I knew I was ravenous for respect; I just didn’t know I needed the tender reverence of accuracy, too.

Hustlers is drawing plenty of praise for showing the relationship between the dancers, and I can attest the sisterly dressing-room tutorials are genuine. Looks-wise, I was never a stunner, instead occupying a spot on the pleasant-but-not-heartbreaking Laura Linney–Laura Dern axis. But, descending upon me like a team of Disney fairy godmothers, my co-workers taught me there was plenty to work with and plenty of ways to maximize my money. Onyx cupped my breasts and, squeezing them and lifting them, said, “Get a push-up bra.” Knowing you couldn’t quote the price of a lap dance in our club lest you get busted for soliciting, Phoenix taught me how to discreetly twiddle a twenty-dollar bill against my thigh and say, “Do you have inspiration for me?” Velvet (and also a non-stripper ex-girlfriend) got me saving and investing: Pass on the Louis Vuitton Neverfull, sink those dollars into an index fund instead.

Perhaps most moving to me is that the film is presented as feminist, with a pink-collar working-class heart. (If you don’t think sex work is a women’s issue, honey, who do you think is doing this work?) Lorene Scafaria’s screenplay makes clear the forms of exploitation at play in the club: extortionate stage fees and tip outs paid by dancers; the economy of derision and insult that certain customers feel is their masculine right. Britney’s “Gimme More” figures large in one Hustlers scene, both as a rogue girl-power inducement and a sly statement on the slippery slope of acquisitiveness. It was a little too relatable, on a few too many levels. For me as a dancer, it eventually started to feel that in order to get more, I had to be more: more attractive, more willing, more popular.

I recently found my old tip-tally sheet from back in the day, and I remember feeling so terrible at the time that I only made $5,700 one month, over 14 shifts. Adjusted for inflation, that is $10,000 today. Cash. My self-worth vacillated based on market demand. A good night could whip me into the stratosphere, but a run of bad shifts could fling me into the dirt. Without realizing it, I was developing a bizarre competitive workaholism turned inward as feelings of self-loathing and inferiority. If I made $500 a shift, I told myself I could’ve made $800. What else could I do to get ahead? I could fit into a size 4 dress, but the more popular girls were a size 2 or a size 0. If a man can have anyone he wanted — after all, what is a strip club but a buffet of female beauty and attention — why should he choose me? The enhancements beckon: bigger hair, deeper tan, longer nails, poufier lips.

Hustlers might contain an excess of femme-y consumerist montages set to banging musical cues, but I don’t begrudge Scafaria’s hustlers their ungapatchka shopping sprees. (I only got rid of my full-length black mink a few years ago; it languished in cold storage from the start anyhow.) I, too, felt my purchasing power pushed along on spurts of adrenaline and cortisol, in an industry that accepts that your primary assets are your youth and beauty. My gorgeous, top-earning, 32-year-old friend was fired from our club with the chilling “we need to make room for the 18-year-olds.” Chop, chop, spandex Cinderella.

Gimme more, indeed.

When Ramona exhorts, “The whole country is a strip club. You have people tossing the money and people doing the dance,” I said damn out loud. The reductionism is so simple yet so toxic. As this movie expertly limns, through the most egregious real-life example, sometimes you don’t realize you’re behind the game until you’re caught in its gears. If a woman walks out of a Hustlers theater wanting to be a stripper, she isn’t paying attention. (And honestly, our hardworking dancers aren’t looking to grow the ranks anyhow.)

I left the world of strip clubs in part because I’d grown toward other professional opportunities, but also because, after fearing for so long that I’d eventually age out of the key stripper demographic, I was simply burned-out. When I stashed away my glittery Pleasers for good, I was solvent, more worldly wise, and utterly, utterly fried. I pledge to affirm stripping as a legitimate job choice. Always. But stripping changed me, I mean changed me, in ways that no other job I’ve held has. What was I to do about the suspicious gap on my résumé? Or the co-worker at my first straight professional job in Manhattan who outed me in the local gossip pages? What should I do about the former customer who tracked down my mailing address and wrote to me years after I quit? Or my rib cage, which has a permanent flat spot on the left side from where it slammed against the pole each time I flipped my body upside down?

And what about the shame? More than once, I’ve had a man (straight or gay) or a well-meaning civilian woman say, “You shouldn’t be ashamed!” But that’s not how it works. It’s not a matter of deciding yes or no. Shame is a stealth agent. I’ve been ambushed by it many times. Earlier this year, I was looking for a Mother’s Day card, and found one from Hallmark that said, “I’m not a stripper. I’m not in prison. Nice job, mom!” You may formally renounce shame, yet people keep thrusting it at you anyway. Even in the greeting-card aisle. Even 20 years after you quit.

There’s a whole other movie to be produced about this: life after the hustle. But Hustlers is a shameless introduction to the temptations and pitfalls of the game while you’re still trying to run it. I may be in the aftermath phase, examining and trying to heal the sinister bite at the core of body-business capitalism, but I also know that for all the downsides, that silvery air of stripping your way to material advancement is still bracing and real — right down to the dressing-room camaraderie, designer purses, and bloody shoes. Regardless of whether a hustler’s coming up, cruising along, or crashing down, I’m rooting for her. And so is this groundbreaking film.

That doesn’t mean it’s flawless. Sex-worker activists have already pointed out some problematic aspects of the film, and emphasized the lacerating irony of strippers and sex workers being shadowbanned on platforms like Twitter and Instagram at the same time a sex-work film is a bona fide social-media sensation. It’s a double bind that sex workers have endured for ages — being a subject of media fascination while having your mobility hobbled by law, policy, and social custom. The frustration is understandable, palpable: For Christ’s sake, don’t just ogle — do something! My hope is that this embellished true-crime story will only further the conversations needed to bring about real-world change. This, too, is my prayer.

Stripper Jesus, bless the Hustlers. Bless us every one.

More on 'Hustlers'

- Stalking Janet Jackson, and Other Stories Behind the Hustlers Soundtrack

- In Hustlers, Jennifer Lopez Proves the Power of the Movie Star

- How Hustlers Pulled Off the Meta Cameo of the Year