Ava DuVernay’s miniseries When They See Us, about the wrongful imprisonment of five teenagers accused of assaulting a jogger in Central Park, is up for multiple Emmy awards this Sunday, including miniseries, direction, writing, actor, and (twice!) best actress. After choosing it as the best miniseries on TV earlier this year, we asked DuVernay to talk to us about the direction, writing, and overall conception of the project. When They See Us is thematically and politically consistent with her earlier work in both fiction (Selma, Queen Sugar) and nonfiction (13th), in that it focuses on racial and class inequities and the idea of prison as the continuation of slavery by other means. But it also represents a level-up in artistry and a culmination of everything she’s done to date, drawing from ’70s New York cinema, mid-20th-century photojournalism, historical research, Hollywood-scale epic sweep, and grounded human drama.

DuVernay is a student of cinema history as well as an influential filmmaker and social commentator, which is one reason why it’s always a pleasure to talk to her about cinema, television, and American history.

How did you approach the cinematography, having a large cast of actors of color with a wide variation in skin tones?

This story was a chance for me to continue exploring how to capture skin tone with actors of color in dark spaces. I was really pushing myself in terms of the color grade. It was the work with Mitch Paulson [supervising digital colorist on several DuVernay projects, including A Wrinkle in Time] that was new, the furthering of playing with the image and seeing what it can do. We were asking, “How far can you push an image before it breaks?”

Can you give me an example?

The section of episode four where Korey Wise is in solitary. It’s shot dark but then we put light in, and that forced the picture to break apart a little bit. It’s barely noticeable to some eyes, but on other screens, you can really see it. That’s important to us because when we’re talking about Netflix, we’re talking about no uniformity of screens, right? It’s gonna look different to someone with an old TV, as opposed to somebody who bought one this year or last year. This is a consideration filmmakers have to really pay attention to now.

How do you feel about that?

It’s not a drag to me. I love that young people are watching When They See Us on their phones, I love that people are watching it on their iPads, I love it that folks were watching it on huge screens.

It doesn’t look like you did a lot of obvious lighting with a capital L.

Well, it was very lit! We just lit so that it doesn’t look like it’s lit, you know? It’s difficult to hold that many different skin tones of color in the same frame without careful lighting, especially when you shoot something the way we shot this. You have to introduce more light to create the proper [visual] balance when someone like Asante Blackk, who plays Kevin Richardson and has a lighter-brown skin tone, is sitting next to an actor like Ethan Herisse, who plays Yusef Salaam and has a much richer skin tone. But we tried to do it so that you weren’t thinking about how it was lit.

What kinds of tricks did you do to pull that off?

In the courtroom scenes, that’s a stage, not a real courtroom. It was built for lighting a lot of people. When you look closely, you can see that there are all these windows built into the set. There’s [artificial] light beyond the windows that’s being pushed in so that it feels like natural light.

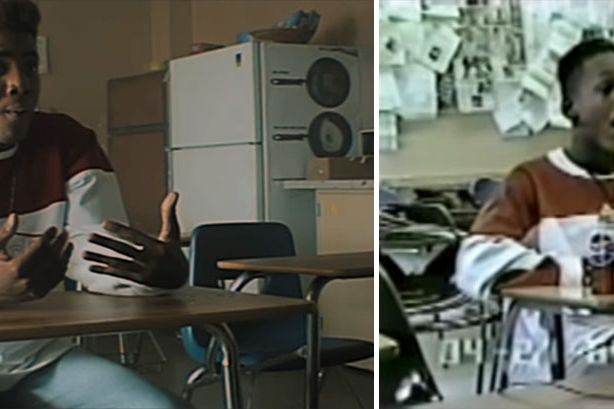

When you were restaging some of the videotaped “confessions,” you matched them closely to the archival video. Why?

If I know exactly what the place looked like because I have video footage, then why would I not make it look like that? That footage is infamous, particularly in the black community and the justice community. It would’ve felt weird to take some artistic license with footage like that — something that we’ve seen and that we knew to be true. So down to the soda can on the desk of Korey Wise, down to the angle that captures the refrigerator in the back, we wanted to get as close to the real thing as we could to honor what really happened in those rooms. It just felt like the right thing to do.

Also I was fascinated by those frames. There’s a point where Kevin Richardson’s coercion is being taped, and there’s a coatrack behind him with a black coat on it. As I watched the real tape of the real boy, whenever he would swivel in his chair, this black coat would come to life and move like a man standing behind him. It was, artistically, for lack of a lighter term, fascinating to look at old footage and ask “Why is this so compelling?”

Why do you think those ordinary frames are compelling?

Because there is a great tragedy happening within those frames. Think about the environment being so ordinary. The flyers in the background for D.A.R.E, the stuff telling you “Don’t drink and drive.” And meanwhile, this injustice is happening.

Do you think the way interrogations and confessions are videotaped has an influence on how the public sees the individuals in those frames?

Yeah, absolutely. We know the image has been used as a tool for bias since the birth of the image.

It was true with drawing and painting; the introduction of photography was supposed to change all that, because, for the first time, it was possible to push a button and record reality. But that’s not what happened.

No, it isn’t. Frederick Douglass, the most photographed man of his century, understood the importance of the image in the sad exercise of having to humanize oneself. Everyone has always understood the importance of the image and the importance of being in control of the image, whether it’s the white people who murdered black people by lynching and then took photographs and put them on postcards and mailed them around the country as souvenirs through the U.S. postal system, or the photographs that black people took of themselves fairly early in the age of photography, when it was considered very rare for people like that to even have access to those sorts of tools.

The importance of controlling the image answers the question of why there are very few black films from that time. The hostage-taking of the image is something that happened because of a lack of access to tools, because of a lack of access to exhibition and distribution, because of a lack of access to the tools that captured who we were, and because of how images were distributed falsely with a different and untrue narrative. Every time a filmmaker of color makes a film, it is a rescue effort. It is an act of resistance and defiance to use tools that were kept away from us, tools that were used to harm us for so long. When I get to a film like this, where there are so very many black people in it, every frame becomes a vitally important demonstration of freedom.

What kind of freedom?

Freedom to be seen, to show yourself as you are without contrivance and without someone else’s truth being put on top of yours.

I noticed that you keep the camera far back a lot in this series. You don’t go in close unless you really, really feel like you need to. Why is that?

It becomes melodramatic. You don’t want to use the close-up all the time, because it loses its power. We go close up on Kevin Richardson’s face in episode one, when he’s telling the lie. When you see him constructing the lie, it was a lot of “You sure you don’t want to cut?” I’m like, “Yup, I’m super-sure.” You got to save his close-up for that moment in the cell with all the boys, where he says, “I lied on you.”

He’s struggling to say the one thing that no prosecutor, no one else said: I’ve made a mistake. I was wrong. He was the first one to say, I did something that I know is not right, that my mother told me was not right to do. And it was in that moment that they decided, all of them, that they would never lie again. And they never did. How do you express that moment? I remember saying that had to pop out, but I don’t know if it was super-conscious. It’s more intuitive. Like, I’m going to need this [close-up] as a big weapon, so let’s save it.

Did any films or schools of filmmaking inspire you, particularly when you were shooting the faces of child actors?

We looked at a lot of photographs. We looked at a lot of Roy [DeCarava], we looked at a lot of [Gordon] Parks. We looked at a lot of Vivian Maier. I watched Battle of Algiers a lot because I wanted that very naturalistic, “Is this real?” kind of feel. But I can’t say we did a lot of conscious borrowing.

Is it fair to say you were thinking about documentary and photojournalism?

Yeah, but I wasn’t trying to make it look like it was news. I know we’re constructing a cinematic image. Intuitively, we knew what we wanted to do, so I can’t say honestly that it was like, Yeah, this is going to be like documentary and news footage.

I have questions about a couple of the music choices. The first is the use of “Fight the Power.”

That was a debated one.

The year 1989 is right there in the lyrics, so there’s a practical reason for using it. But it’s also, of course, the theme to Do the Right Thing. Out of all the songs you could have chosen, you chose that. Why?

Well, that song is formative for me personally. It was a big, big song for me. That was the summer of me going into my senior year.

It also gives you an immediate sense of place. If you loved hip-hop, you loved that song. If you were around during that time, you know that song was going to put you right there. There was no heavy lifting that needed to be done. I’m consciously recalling Spike’s work and Public Enemy’s work in that moment and saying, You know what this is; this is where you are. And the lyrics also fit so beautifully into the fight that’s ahead. It’s a tribute but also a testament to the power of that work.

The other one I want to ask about is “Moon River.” Unless I’m missing one, you use it twice, right? But it’s not the Audrey Hepburn version from Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Why that song, and why that version?

You’re the first person to ask me about it.

That’s why I get the medium bucks.

That song has always been a heartbreaker for me. I did not know it in the context of the Audrey Hepburn [movie], but that’s a meaningful song to me. There’s a mournful quality. There’s a longing in the song. It is like an elegy. It speaks to a desire for something more that most people will never get. It’s all the things that are just out of reach. And so that song applied to the black image is something I’ve always wanted to do. I played with putting it in Middle of Nowhere, putting it in Selma, and I’m glad I wrote that part into episode four. It came from a story I heard from Korey Wise. People do all kinds of things in prison, and he told me about a guy who would sing. It always stuck with me. The fact that that man sings that song — in this demonized forest where the people ensnared in the system can’t even hear it or see the beauty in it — this is meaningful to me.

The artist at the end is Frank Ocean. He’s meaningful in the culture for a lot of reasons, but it all seems to be a real symmetry. A voice of a black man creates a certain kind of full circle–ness to thinking about what is within the reach of some citizens and what is not. Who gets to sing that song? Who doesn’t? Who can really hear that song, and who can’t and why? I’m proud of those moments.

You have two sets of actors for each of the main boys, except for Jharrel Jerome. Why did you have him play both incarnations of Korey?

Because he has the physicality to do both. A lot of the boys that we cast, they would not be able to pass as men. The men that we cast, none of them could play boys ’cause they look like full-grown men. It was only Jharrel who was able to do both. When we shot him, he was 20, so he looked very close to a teenager, but with the full-grown beard he can literally pass for 30.

The structure of this entire story is fascinating to me. In the first two episodes, you concentrate on the arrest, the trial, and how these kids get into the system, and then you go to the immediate aftermath of the release and the difficulty of reintegration for three of them. Then you concentrate on just Korey. How did that come about?

It really came from Korey Wise. When I first sat down with him, he said, “I’m happy that you’re telling my story, but you should know we’re not the Central Park Five. We’re four plus one.” He was adamant and assertive about that, that they did not all experience the same thing. From the minute he told me that, I knew I needed to find a way to honor that in the story. Before I even opened a writers’ room or hired any writers, I knew he would have a stand-alone episode and that would be the finale.

Obviously, you tell a lot of different stories, but you keep coming back to the misapplication of criminal justice to people of color. What about this story brought new understanding to you as an artist?

The sprawling nature of this story forces the storyteller to have to understand all of the different parts of the criminal-justice system in real time, so whereas I had studied those things from a historical framework in order to make 13th, this film allowed me to really interrogate it from a personal and emotional place. All of the levers of the criminal-justice system that I talk about in 13th, I really began to feel them on When They See Us. When we talk about bail, when we talk about debtors’ prison, when we talk about solitary confinement, when we talk about police aggression, when we talk about the bias in the criminal-justice system, it was digging into each of those pieces that I knew theoretically — that I knew politically, historically, culturally — and getting on a level where my heartbeat was beating with the people going through it.

I’d never gone deep inside of the prison and dealt with the whole trajectory of criminalization. The sweeping nature of the case is that it touches almost every aspect of the criminal-justice system. It allowed us to share all of that emotionality that’s bumping up against the hard walls of the system and really open up these spaces in a way that I really longed to do, hadn’t seen, and wanted to have seen.

This interview has been edited and condensed.