There’s a short montage in the trailer for Bill Burr’s new Netflix special Paper Tiger that cuts various moments in the special into one brief run of Burr yelling hot-button phrases in mocking tones. “The #MeToo movement!” he yells. “White male privilege! Hipsters! ‘I’m a male feminist!’” “By the way, this is gonna be my last show ever,” the trailer cuts to Burr saying next. The implication of a trailer like that, and of much of the buzz about Burr’s special, is that it is a middle finger to civility, a takedown of PC culture. It’s positioned as one more in the recent run of comedy specials that respond to straw men like “cancel culture” and “safe spaces” by deriding them, pushing back at audiences for their sensitivity and inability to take a joke. Cut into the trailer as it is, Burr’s “This is gonna be my last show ever” line sounds like he’s about to be so provocative that he will never be allowed onstage again.

The opening of Paper Tiger feels like Burr leaning into exactly that proposition. For the first several minutes, he flips quickly through complaints about the overanalysis of jokes, how white women are to blame for the current lamentable state of culture in the United States, and jokes about disabled characters being played by able-bodied actors. In his biggest and most convincingly risky swing, the first few minutes include a bit about Michelle Obama. Burr, in full character as angriest man in the world, is not a Michelle fan. It is an opening segment that dares you to turn the special off in disgust — the kind of opening that makes the special’s closing credit for executive producer Dave Becky utterly unsurprising. It is exactly what the trailer suggests Paper Tiger will be: furious, resentful troll comedy that plays like a toddler yelling the only swear word they know, desperately begging for someone to punish them.

It’d be hard to blame anyone for turning Paper Tiger off at that point. Misbehaving toddlers grasping for parental boundaries are no one’s idea of good company. The thing is that once Burr moves past that part of the special — once he gets through the sexist throat-clearing and the tick-the-box list of rebellious trollish vocab — the rest of the special is different.

It doesn’t look that different on the surface. Burr rags on his wife, calls sexual assault funny, and puts on a stupid voice and mocks male feminists. He makes fun of the idea that culture can be appropriated. He talks, wistfully, about a time where there will be high-quality sex robots so that women are no longer necessary. You could imagine versions of all of these jokes that are absolutely in keeping with the opening several minutes of his set, versions where they’re jokes about victimhood or oversensitivity. In every one of them, though, Burr at some point flips the switch, and unspools the initial premise of the joke.

“Sexual assault is funny,” Burr begins, before telling a story about a woman touching him inappropriately before a show. In his telling it is funny, because he’s quite capable of pointing out the absurdities of the situation. He plays up his futile inability to respond after the act, and how thoroughly he’d be mocked if he tried to explain his discomfort to other men. “Eyyyyy flick my balls!” Burr yells, in consummate character as a clueless asshole who Burr imagines laughing at this story about a man being assaulted by a woman. It becomes a joke about Burr wrestling with the intractable gender politics of vulnerability. It is a joke about how sexual assault has nothing to do with sex and everything to do with power. It’s so far from his opening lines about how #MeToo has robbed men of due process that it feels like the message could’ve come straight off an anti-Trump protest poster.

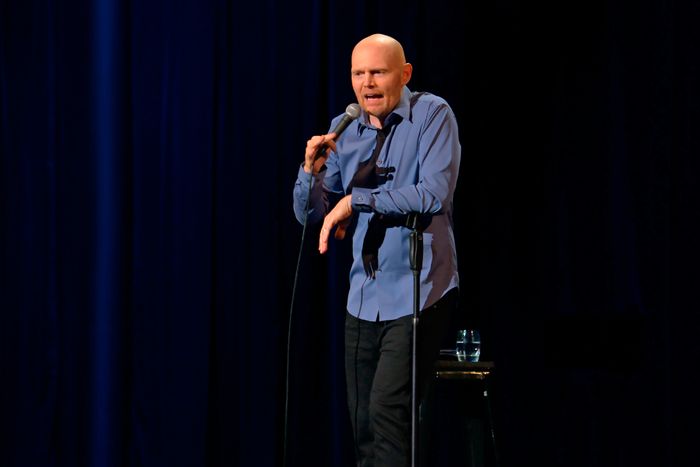

Aside from the opening several minutes, Burr’s whole set is like that: thoughtful, surprising, introspective. He keeps yelling, of course, as if by bellowing his ideas while striding angrily around the stage he can distract from the fact that he’s delivering jokes so sensitive that some border on sweetness. In one of my favorite sequences of the special, Burr dramatizes the experience of watching a documentary on Elvis together with his wife. While he watches along in interest, he notices that his wife, who’s black, is making frustrated sounds at various moments of racism in the Elvis story. Burr turns his exchange with his wife into a canny stand-in for a clueless white troll arguing with a black interrogator, where Burr takes on the role of MAGA provocateur and his wife is the exasperated voice of the “liberal elite.”

Burr, telling the story of this fight with his wife, describes himself trying to defend Elvis against accusations of racist cultural appropriation. Sure, Elvis may have stolen his dance move from a black person, but where did that guy get it? Why is it “carrying on the tradition” if the move was adopted by a black person, but “stealing” if Elvis does it? A lesser joke could easily end there, passing off that anemic observation as a comedic insight. But Burr goes on, first voicing his wife’s explanation that Elvis reaped endless profit and cultural acclaim while the original innovators did nothing, and then his admission that yes, she is right. He then goes on to spin the joke again, digging deeper into his own humiliation and then landing on a punchline that, almost miraculously, reinstates his ability to control a joke while also mocking his original cluelessness.

Paper Tiger is primarily fueled by shame — by Burr’s own shame in himself and his efforts to be a better person for his family and his own future. Over and over again, in his jokes about his childhood, marriage, his dog, and even his extended bit about sex robots, Burr probes the damage done by his own shame and emotional repression. The first several minutes of the special make it seem as though the paper tiger of the show’s title will be the overly sensitive audience, or snowflake culture, or women in general — scary, toothy beasts who will crumple at the slightest pressure. In the next 50 minutes, though, it’s clear that the paper tiger is Burr, roaring with all his might and then explaining exactly how embarrassed he is by his own fragility. It’s frustrating that Burr feels the need to start by roaring so aggressively, because anyone who showed up to see a tiger is actually getting something subtler and more carefully crafted.