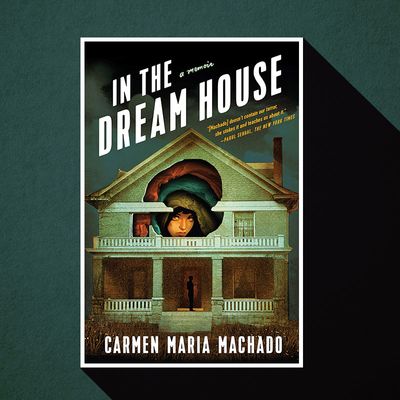

Carmen Maria Machado’s second book, In the Dream House is unlikely to resemble anything you’ve read before. It’s both a memoir of her toxic relationship with her first girlfriend and a history of queer domestic violence with chapters that dance between genres. Some read like fairy tales, others like horror stories; there’s a choose-your-own-adventure section. While her story will resonate deeply with some, others may feel that whatever Machado says her ex-girlfriend subjected her to (manipulation, deceit, screaming rages) didn’t rise to the level of abuse. Machado is well aware of this. “It’s inevitable,” she told me. As she showed in her dazzling 2017 debut, the story collection Her Body and Other Parties, she explores subjects many would rather avoid. “I speak into the silence,” she writes in the new book. “I toss the stone of my story into a vast crevice; measure the emptiness by its small sound.”

Your first book, Her Body and Other Parties, was a huge success; now, there’s a TV adaptation in the works. How did it change your life?

Before the first book came out, I was just trying to gain purchase in my career in various ways. The success of the book really surprised me. It still does. Every week, there are like 200 or 300 copies sold, and it’s been out for two years now. It gave me space to be an artist. It got me to a place that I thought I would not be in for a long time. It made me able to live a life I want to live.

Why did you want to do a memoir as your second book?

[Laughs dryly.] I don’t know that I necessarily did. When I was editing Her Body and Other Parties, Graywolf [my publisher] asked if I had anything else for them to look at. I thought the draft was really a mess — it was so disjointed, obviously unfinished — but my agent thought we could sell it. He could see the finished thing in the skeletal draft.

The book is such a wild mixture of genres and forms. It’s grounded in your memories, but also weaves in historical episodes of queer domestic violence and fairy-tale tropes. What was the editing process like?

When I first handed it to my editor, it wasn’t in any discernible order. The personal material was in a rough chronological arc, but that was about it. I would just go off on these kicks, like, “Here’s a huge chunk of historical material.” I knew it needed to be spread out, but I didn’t even know how to begin. Eventually, I just asked my editor if he could do it for me, and he did.

Why do you think you couldn’t put it into order?

I was really exhausted and sad. I [had] also never worked on a full-length book before. [My wife] Val told me how an old writing teacher of hers used to say writing a full-length book is like falling into a bowl of spaghetti. You’re trying to pull all the noodles together but it’s really hard because you’re just in this bowl of noodles.

What was it like to write about something so personal and so dark as your first full-length book?

It was horrible. It made me more depressed and kind of killed a little part of me. I was sitting alone in a little cabin in New Mexico trying to write about the worst thing that ever happened to me. I thought I was ready to write the book, and I don’t know if I was but I did it. If I said it was a good experience, I’d be lying. It was not a good experience at all.

How did you keep going?

I didn’t want to give the money back.

Practical.

I also thought, Well, I could have taken more time with it. But then I would’ve spent more time with it, and I wanted the work to be done. That’s my personality. I had a foot surgery this summer, and I had to do one on the other foot too. I asked my doctors, “Can you do both feet at the same time?” They were like, “No, that would be terrible.”

Did you at least feel that, by the end, you had exorcised something?

I think so, in the sense that I’d been trying to write about this for a really long time and I’d mostly not succeeded. I’m proud of this book, but it also made me think about stuff I could have done differently. In that sense, I’m not exorcised, because the ghost is still there. It’s still present, it’s just contained. I don’t know, the metaphor’s getting away from me.

That makes me think of your idea in the book about the theory of time travel, that even if you could go back, you couldn’t actually change anything.

There’s nothing I can do except tell the story. I try not to have explicit social goals for my work, but I’ve already gotten messages from people telling me they have experienced similar things that they’ve never seen represented before. Queer domestic violence is not a topic that’s been written about a lot.

Why do you think that is?

I think this is one of the failures of the conversation around #MeToo. People really struggle because they want these super-concrete examples. It’d be easy to say my girlfriend was actually a boyfriend, and she — he — gave me a black eye, here’s a photo, here’s the police report. It’s way more complicated to say, what does it mean for somebody to psychologically torture? Can women abuse other women? Of course they can, but what does that look like, and why does it matter, and what kind of betrayal does that feel like?

You’ve always been interested in the murkier regions of #MeToo.

That is always my project. How do we think about coercion and sexism as it exists in more subtle ways? We like to think of #MeToo as these perfect open-and-shut cases of, like, Aha! He pushed a button and locked the door behind her. Not to bring up fucking Jeffrey Epstein, but literally that’s the stuff that movies are made of. I’m more interested in the stuff that’s not so easy to name. I’m interested in trying to give people language to talk about things they don’t think they have the language to talk about. Is it the most noble of pursuits? I don’t know. You tell me.

Has anyone challenged the idea that your emotional suffering was abuse?

Not yet. I feel like it’s inevitable. People have already said that to me about the experience itself — people that I actually cared about. Or people who were supposed to protect me and help me.

Anyone in particular come to mind?

There was this person in an administrative capacity at Iowa [Writers’ Workshop]. My ex was coming to school there, and I tried to explain to [the administrator] what had happened to me. She told me, “Sometimes relationships are just bad.” After, I remember sobbing and thinking, This is what people will always think. The idea of people I respected thinking I was just some weird, hysterical scorned lover — it was unbearable. Maybe that did play into why I decided to write the book. This feeling that if I don’t, nobody will ever understand.

What do you think you wanted from that administrator?

I don’t know if I know what I wanted. I think I thought, very naïvely, I am a student here, if I tell somebody and try to explain this, I will be helped in some way. What I didn’t realize was that that’s not what institutions are for. I’ve learned better now. Institutions are not designed to help individual people. They’re designed to maintain their own longevity.

I spend a lot of time talking to my students about this — how institutions exist to preserve their own power, and they will only act if they are really pushed into a corner where that power is threatened. I tell them, “Yes, the world is full of good people, but it’s also full of people who will think nothing of crumpling you up into a little ball.”

How do your students receive that information from you?

They laugh nervously. I want to save all of them from something, and I can’t. I want to tell them that relationships are hard, but if your significant other throws something at your general direction, even if it doesn’t hit you, that’s fucked up. If someone touches you without your permission, even if it’s someone you’re in a relationship with, and you tell them not to and they keep doing it, that’s not okay. Everybody cries in relationships, but if you’re crying every single day of every week of every month, that’s not normal. But I can’t walk around saying that to everybody, so I wrote a book.

You write quite a bit about your sexual relationship with your ex, especially at the beginning of the relationship. I’m curious how you think your attraction to her played into your willingness to stay, even once things got bad.

She wasn’t my first female lover, but she was my first girlfriend, and we had a deeply sexually compatible relationship. No one had made me feel that way before. Like — “You’re beautiful and special and I love you and I wanna have sex with you.” There’s no point in denying that it’s really intoxicating. Especially when you’re a fat chick who’s been told, maybe implicitly, that you’re not somebody worth desiring. I was like, Wow, I can have that, this thing I’ve always wanted. It was a perfectly Carmen-shaped hole, and I fell right into it.

I think about my own naked desire. That’s not even about her, it’s about me — what I needed, and how nakedly I needed it, and how easily I was lured, like it was nothing, like you’d lure a dog with a little scrap of garbage, like it’s not even a steak. That’s humiliating to think about; it’s humiliating to write that; it’s humiliating to remember it.

Why do you think it’s humiliating to think about that desire?

[Long pause.] I don’t know. I guess because I’m gonna have to stand in front of people and say, “look at me, I wanted this thing, and I wanted it so badly that I gave up almost everything I was and almost destroyed myself in the process to get it.”

Have you had you had any contact with her? Does she know you’re publishing this book about your relationship with her?

I cannot speak to that either way.

Do you feel prepared for all these thorny issues to come up on your tour, or on Twitter, or in books reviews?

I’m prepared for it. At least, I feel prepared for other people to have that conversation. I don’t have to have that conversation with anybody. I wrote the book, you know? I’ve had my half of the conversation. Besides, by now, there’s nothing anyone could say that I have never thought.

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado is out November 5 on Graywolf Press.

*A version of this article appears in the September 2, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From Fall Preview

- The Best Classical Music Performances to See This Fall

- Anthony Roth Costanzo Is the Pharaoh We Need

- The Canadian Cree Artist Remixing History in the Met’s Great Hall