Not so long ago, it was touch and go for the X-Men. Their adventures in the pages of Marvel Comics were hardly making a dent in the minds of the average reader. This may have been by design, to a certain extent, possibly owing to the fact that Marvel’s parent company, Disney, didn’t have the X-characters’ film rights. Although there’s never been formal confirmation of this policy, it’s long been said that Marvel Entertainment CEO Ike Perlmutter issued an edict at some point in the 2010s: Screw the X-Men. Though those rumors are probably more extreme than what actually happened — there was still A-list talent being put on the X-books here and there, like writer Brian Michael Bendis or artist Stuart Immonen — you couldn’t shake the feeling that Marvel was spending far more money and energy on fostering titles that starred characters who also appeared in Disney’s Marvel movies. Whatever the reason, the X-Men series stopped presenting big, grabby ideas. Even when talented writers were assigned to guide the mutants, the stories felt like empty nostalgia exercises filled with half-hearted quips and small-scale threats. Nothing was catching on.

Well, suffice it to say that all that’s changed, and it turns out that all it took was the deft, firm hand of a 46-year-old former architecture student. Jonathan Hickman — a lifelong geek trained in the art of designing buildings before he worked in advertising and then decided to try his hand at comics writing in the mid-aughts — recently took over scribe duties on Marvel’s X-Men comics. Reading them now is like falling in love after years of luckless dating. Hop onto Twitter on a given Wednesday, the day new comic-book issues come out, and you’ll find the tag “#xspoilers” — so named because users can mute all tweets with that tag if they haven’t had a chance to read the new issue yet and aren’t ready to join the conversation. But when they are ready, what a conversation there is to be had. People are screenshotting their favorite moments left and right, tossing out their theories about where it’s all going, dissecting all the metaphors and references, and just generally squealing over how into it they are: “We’ll be talking about what this issue MEANS for a long time but I could spend hours just talking about how it LOOKS,” they say; or “it’s just fucking fantastic”; or simply, “THIS IS SOME WILD SHIT.”

This kind of broad-based positive consensus about a superhero comic is a rare thing — yes, there have been series that were widely praised in recent years, but the response from critics and fans for the nascent Hickman X-Men run has been especially pronounced. He’s launched this new stage of the X-mythos with a story that’s divided into two miniseries, House of X and Powers of X, which is actually pronounced “powers of ten” for reasons that I won’t spoil for you. But that kind of playfulness with form and language is emblematic of what Hickman does best.

He’d been raised on comics, and one set of characters, in particular, had always appealed to him: the (not-so-)merry Marvel mutants known as the X-Men. “It’s the Marvel comic I read growing up — the one I’ve always wanted to do,” he tells Vulture. However, it took him 12 years of professional comics writing to get around to writing them. He started his comics career with strange, high-concept indie titles at Image Comics, then got a bump up to Marvel a decade ago to write the series Secret Warriors and Fantastic Four. The latter of those two titles was what made him a star, and it did so abruptly. His time with the FF — the first superheroes of the Marvel Age of Comics back in the 1960s — was a joyous and intriguing one from the very beginning. He wove big ideas into wild adventures, and the whole endeavor felt as fresh as it was respectful of the characters’ long legacy. Fans and critics devoured it.

As the years went on, it became clear that Hickman’s vision was too big for one set of characters. He wrote a series called S.H.I.E.L.D., which audaciously rewrote the history of the entire Marvel Universe by establishing its roots in the actions of figures like Michelangelo, da Vinci, and Tesla. He reinvigorated the ailing Ultimate Marvel experiment. He was assigned to the tales of the Avengers and took them to the ends of time and space. What’s more, all of these stories linked up with one another, effectively creating a kind of Hickmanverse within the Marvel U. It all culminated in one of the best superhero crossovers in history, the jaw-droppingly ambitious Secret Wars. And then, it seemed, his time with the superheroes was over. He left Marvel in 2016 and dedicated his efforts to his various creator-owned Image titles, seemingly content to tend his own garden and get weirder and weirder with characters he created and owned, alongside his artist collaborators. We counted ourselves lucky that we’d been able to see him experiment with what superhero fiction could be but didn’t hold out much hope we’d ever see him do it again.

Then, earlier this year, there were whispers within the comics rumor mill: Hickman was coming back. What’s more, the gossip was that he’d be taking on the woefully abused X-Men. From the 1980s through the mid-aughts, the X-titles had been Marvel’s flagships, outselling just about everything else on the market and establishing a mythology whose popularity catapulted them first into a successful Saturday-morning cartoon show and then a megahit film series. However, that film series proved to be their undoing. Owing to various machinations not worth getting into here, 20th Century Fox owned the movie rights to the X-Men, and when Marvel started making its own movies with the characters whose rights it still retained circa 2008 (the ones in the Marvel Cinematic Universe), the company had an incentive to promote the Avengers characters more than the mutants.

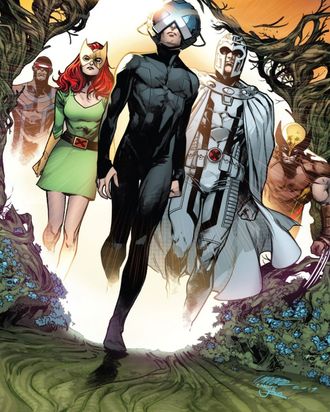

Those days are gone. Two things, which may or may not be related, happened in recent months: The Disney/Fox merger meant the X-Men were back in the film family, and Hickman was announced as the writer of House of X and Powers of X in March. This summer’s San Diego Comic-Con brought news that the miniseries would be followed by a new line of X-Men titles, with Hickman writing the main book and others operating under his guidance for secondary series. We waited with bated breath to see what could happen. Finally, in late July of this year, House of X No. 1 dropped. It was an immediate sensation. There have only been a few subsequent issues of the run — the House of X No. 5 came out yesterday — but geeks have been poring over every page like it’s a new Gospel.

The basic setup is as follows: The X-Men, led by mutant telepathic genius Charles Xavier, have decided to form their own sovereign state on the island of Krakoa, a living geographic entity that has its own mutant powers and has been part of the X-Men mythos for a long while. This turn of events upsets the balance of global politics and economics, and, although the mutants seem to have created a self-governed utopia, we have swiftly been shown, through time-jumps in subsequent issues, that everything is destined to go horribly wrong.

These are not wholly unfamiliar tropes for X-Men die-hards, but Hickman, pencilers Pepe Larraz and R.B. Silva, colorist Marte Gracia, letterer Clayton Cowles, and designer Tom Muller have turned them all on their heads and crafted something that feels new. Let us dwell for a second on that last job title: designer. In Hickman’s Image series The Black Monday Murders, he toyed with the very foundation of the comics medium by interspersing typical words-pictures-panels sequences with pages and pages of innovative, text-based portions that are arranged with sleek charts and graphs to resemble dossiers on what you’re reading. They’re not mere grace notes, either — key information is presented in those pages, and their presence makes you wonder just how far mainstream sequential art can go.

Nobody has any idea where all of this is going, but fans are rabidly spewing out speculation in Comics Twitter, Reddit, and blog posts. Hickman is confident that he won’t end up hampered by fandom like the creators of, say, Westworld or Lost, whose shows were overwhelmed by followers desperate to identify future twists. “I don’t really construct stories that way,” he says. “I think if you’re serious about this stuff, it became very obvious during Lost just how intelligent a million viewers working to solve puzzles are. The way you do it is to withhold the information necessary to solve the mystery until right before you narratively present the solution.”

What’s more, it’s all reasonably accessible for the legions of casual X-Men fans who gave up reading the characters after the last truly revolutionary X-run, that of writer Grant Morrison in 2001–4. I can’t really speak to whether a brand-new reader of superhero comics will be able to enjoy what’s going on, but if you’re prepared to peruse a few Wikipedia pages and mostly just let the aesthetics and ideas wash over you, you should be fine.

And those ideas are fascinating. You’ve got meditation on the parallels between the development of artificial intelligence and the evolution of biological organisms. There are explorations of the righteousness and horror of political terrorism. We’re looking at the ways in which the powerful condescendingly extend sympathy to those they are oppressing. Most important, there is a ton of stuff going on about the vital importance and mortal danger of a threatened minority group seeking self-determination and liberation. These are all questions that feel vitally necessary in our present troubled age. Hickman has both found the Zeitgeist and seems to be altering it at the same time. We needed the X-Men, and now — thank the mutant gods — they’re back.