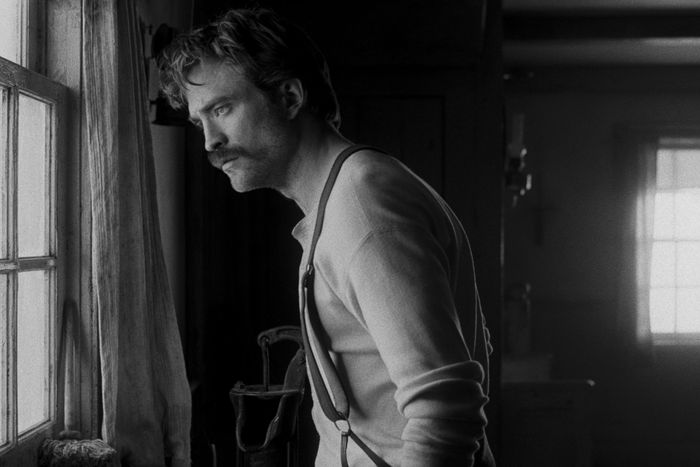

With 2015’s The Witch, Robert Eggers showed that there was nothing quite so frightening as the Puritan mind. By replicating the setting and vernacular of 17th-century Plymouth, his thriller about a family settling in the wilderness immersed us in a particular mind-set and belief system; suddenly, witches were real. Now, with the bleakly gorgeous and impossibly tense The Lighthouse, opening October 18, he places us in a remote late-19th-century lighthouse, where two men — an old sailor played by Willem Dafoe and a novice played by Robert Pattinson — find themselves at odds, driven by drink, savage weather, and mysterious visions.

What comes first for you — the period and the setting or the story?

I tend to imagine the atmosphere of the film before the story. The reason why it became this period in The Lighthouse is because I wanted to have a foghorn, and I wanted to have a Fresnel lens. Fresnel was a Frenchman who designed a lens that could magnify light greatly. [Before that], they used to have oil lamps that had little concave mirrors — many, many, many, concave mirrors that would rotate to reflect the light out. The Fresnel lens looks like a crazy Art Deco sculpture. That was important to having the mystery of the light as a plot device. Having that Fresnel light was going to be key, so actually, this lighthouse is in a state of really terrible disrepair for the period. Before the Civil War, American lighthouses were often shitholes, like the lighthouse station in my film. But then the United States Lighthouse Establishment was established, and it took keeping your lighthouse in good shape very seriously — so you have to imagine that this place was so remote that the inspectors would never come to check it out. Jarin [Blaschke, the cinematographer] and I went to one of the few lighthouses in North America that has a working Fresnel lens, at Point Cabrillo in Northern California, for a research trip. We could have just stared at this thing all night. It is hypnotic.

How do you approach research with these films?

Head on. Maybe I’ll get tired of it but I don’t really have any interest in making contemporary film. Part of what is fun to me is doing the research. If I wasn’t doing this kind of creative work, I probably would’ve been an archeologist — trying to understand where we are, and where we’re going from where we came from, is what is the most exciting to me. The other thing I find, if I ever did do a contemporary film, it would probably have to be extremely low budget. Otherwise, it would be so fussy-looking that it would be shameful. When doing something in the past, I have to create or re-create the material world. That is very satisfying.

Also, I strive for period accuracy, which is not important to good design. In fact, most films that are well designed stray from the path, but I like having the rigor of saying, “This is what we’re aiming for,” whereas other directors or designers have to invent a world. That would be sort of overwhelming for me to have that responsibility. For this movie, certainly it’s very much a collaboration with all of the heads of department, but there is a way in which I’m like, “This is the teakettle that’s supposed to be there, so find this teakettle. I don’t need to see options of ten; I just need to find that one.” I find that’s a very satisfying way to work.

But it’s about more than period accuracy, isn’t it? In The Witch, for example, you immerse us in the psychology of the period, so that we will find the things they found scary to also be scary.

I’m sort of looking for half-forgotten things at the perimeter of contemporary consciousness. With The Witch, there’s the hare. We don’t have European brown hares in the United States, so the witch lore surrounding hares we don’t have — but it’s massive in Western Europe. I was in Northern Ireland recently and talking to someone who hunts hares who was saying, “When I see one of these hares, she’s a witch.” It’s just something that she grew up thinking. So with The Witch, some people are like, “What’s the deal with the bunny?” but a lot of people find that they are really creeped out by the hare and they don’t quite know why.

So much of this film turns on the chemistry between Pattinson and Dafoe. Were you worried at all that they might not have any?

Of course, that was scary. With The Witch and all my theater work, I got to audition people to death and I got to read people together. But when you’re working with names of a certain notoriety, they’re not going to read. So you just have to trust your gut. I’ve been asked before why they seemed like a good pair and I probably should, some morning or evening, give that a good think, because I don’t know why it made sense to me. They have cheekbones and noses. Somehow, the way they looked together was part of it. Especially because this movie plays around with identity in an interesting way. There are ways in which Rob and Willem began their careers more differently, and their approach to the work couldn’t be more different. Though [when you look at] how Dafoe’s continued to navigate his career, and how Rob has chosen to position himself post-Twilight, they are both looking for interesting things. Rob turned down an offer on another film of mine, because he said that while he liked it, “that role wasn’t weird, and I only want to do weird things. This is weird enough.”

As I understand it, Pattinson and Dafoe have very different acting styles and different processes. Does that prompt you to direct them differently?

You have to direct them differently. Every actor demands different things. Every human being you come in contact with in your life, you have to deal with in slightly different ways. And certainly when you’re trying to provoke a performance that will carry an entire movie, whatever works for them is what you have to do. It is a weird balance, because how do I direct with them within what my own approach is? There is friction. I want everyone to trust each other and skip happily down the lane, and I think that finally everyone trusted each other, but we weren’t skipping down the lane all the time. Because they work very differently, it wasn’t always simple — but it was great for the film and very enjoyable. I wouldn’t say that my overall experience of The Lighthouse was fun. It was quite miserable and difficult, but I did have fun everyday working with them.

When you say everyone wasn’t always skipping down the lane, what do you mean?

There are really demanding scenes, and they’re working differently. [With Willem in the finished film] you’re often looking at bits and pieces of all of his takes. And with Rob it’s usually take one or take 57 — all of that scene is one thing. How do you keep that in balance? It’s difficult for everybody. Funny.

There’s this weird romantic element between the two characters. It’s almost homoerotic.

It is homoerotic, but that doesn’t mean that they actually want to sleep with each other. But the way that we shoot Rob’s muscles is homoerotic. It just is.

I was reminded, watching the film, that the image of the lighthouse itself, in culture, is a symbol not just of mystery but also of romance.

Jung would love that. And it is a giant phallus.

You sometimes cut from the machinery of the lighthouse to shots of Dafoe’s body, as if he’s becoming one with the lighthouse.

When Rodrigo Teixeira, one of our Brazilian producers, first read the script, he texted me: “Willem is a lighthouse. Rob is not a lighthouse. This is the movie.”

Can you tell me about the location?

We shot on the southern tip of Nova Scotia in a place called Cape Forchu. That is a peninsula off the fishing village of Yarmouth. It’s just like a spin of volcanic rock, and it was a really, really punishing location. There were several nor’easters when we were building the lighthouse. The seawater was freezing on the scaffolding. The wind is not exaggerated in the film. Even if I was a yard from you, I might not be able to hear you against the wind.

Would the film have been different if the location had been more hospitable?

Oh, it’s intentional. I wanted it to be miserable and challenging.

Your characters often speak in archaic ways, and your stories, despite having genre elements, often move toward abstraction and fragmentation. How do you not lose your audience?

Obviously, you’re afraid it’s not going to work. But Jarin and I, when we’re conceiving the shots, are always very considerate of which character’s point of view the scene is being told from. We make all of our choices based on that, and I think that gives [the audience] something to hang our coats on, so we can feel comfortable.

I was really struck by the sound design of The Lighthouse. From what you’re telling me, it sounds like you probably had to create a lot of that afterward, especially if you can’t hear anything when you’re shooting.

The music and the sound design merge in this film quite often, and there are some things that I would consider music and that composers consider music but that other human beings might consider sound design. [Laughs.] The sound of light over the lens was a glass harmonica, which was sort of perhaps too on-the-nose but I think it works quite well. A lot of friction mallets on various objects — mostly cymbals, but all kinds of musical instruments. There was a point at which Michael Schaefer at New Regency emailed me and said, “The score is terrible, like a Yeti moaning. I beg you to ask yourself, When is the obscurity of the score adding to the tension and when is it just weird?” And that was a very helpful note.

The Witch is often grouped together with films like The Babadook and Hereditary and others in that contentious category of “elevated horror.” What’s your relationship to genre? Does it feel limiting sometimes to have to sell a movie as something specific that then creates all sorts of genre expectations?

Being a wannabe auteur and my favorite filmmakers being part of the dead canon of European, Japanese art-house masters, I want to say that I don’t want to care about genre and how it’s limiting and all of that stuff. And there are some people who stick by specific definitions of what genre is and they don’t like what I’m doing, which is perfectly fine. The Lighthouse isn’t scary. A few people have said it is, but I don’t think it is. I think where genre is limiting is that in the marketplace, you have to put things in a box to create expectations to make a profit, and that’s where you run into trouble. There are people who really do say, “Give me my money back because I paid to get scared and I didn’t ever once throw my popcorn in the air.” That’s fair enough. On the other hand, I wouldn’t have the incredible opportunity to be making cinema if it wasn’t for genre. Genre gave me the opportunity to get a movie fucking financed. The Lighthouse couldn’t have been made without this kind of freedom that is allowed to some filmmakers to be able to play around with genre. Jennifer Kent’s Nightingale [her follow-up to The Babadook] is more horrific than any horror movie — but also, I don’t think you could make that movie without this kind of freedom.

*A version of this article appears in the September 2, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From Fall Preview

- The Best Classical Music Performances to See This Fall

- Anthony Roth Costanzo Is the Pharaoh We Need

- The Canadian Cree Artist Remixing History in the Met’s Great Hall