I don’t think there’s been a time when I’ve visited my parents’ home and there hasn’t been the offer of fruit — cut fruit, specifically, leading me to wonder if there was ever a time when the fruit wasn’t cut. If, perhaps, it just sprouts forth from the land, perfectly sliced.

Cut fruit fulfills the following Jewish-mother rules: One must always have something to nosh on (as one is always hungry); it should be a healthy snack; but would it kill us to make it a little sweet, too?

It takes nearly 19 minutes for Shelly Pfefferman to show up onscreen in the Transparent pilot, with a sensible, short gray haircut, offering to cut some cantaloupe for her daughter, Ali. The scene lasts less than two minutes. This is how we will see Shelly for most of the first season: on the fringes, Jewish-mothering, or at least performing the tasks of a Jewish mother. It is just one of many perfect, character-defining details that made Shelly familiar to me, and my favorite character on the show.

I loved all the Shellyness, the nitty-gritty details that form this variation on the archetype — particularly in the first season. The way she calls her children, at various times, “Dolly.” (I have a second cousin who used to do that, and I heard her voice every time Shelly said it.) She’s a nicknamer, a pincher, a squisher, and a noodge, too. She frets over how other Jews might judge her actions or lifestyle. When her husband, Ed, disappears during episode five, she is less worried about finding him than seeming like she isn’t worried, at least in the eyes of the soon-to-be-visiting rabbi: “I’ll be the talk of the temple, the lady who lost her husband.” When 13-year-old Ali cancels her bat mitzvah in an episode-eight flashback, she says, “Thanks to Ali, I can’t go to the village. If I do, I’m going to run into somebody and then I’m going to have explain and explain and explain.”

Her complex relationship with food, too, made me want to spend more time with her as a character. She eats with a wild focus — either consuming with abandon or pushing her food off her plate. She has a standing order at Canter’s Deli and can tell simply by holding the bags that the order is off. (Ali goes dairy-free for an episode and ordered tofu spread instead.) There’s the bulk-size jar of mustard she carries to Ed’s shiva — to the annoyance of her other daughter, Sarah — just in case more mustard might be needed. To control food is to control life — not just hers, but those around her, too.

What is more elusive with Shelly — in spite of Judith Light’s nuanced, tender, and funny performance of a character written extremely loud — is a deeper understanding of her. At times I felt she was slighted, or made to play the clown in the Pfeffermans’ universe. She is given far less screen time than her family members in the first two seasons, disappearing for entire episodes. She often exists to elicit a response from a family member, frame a scene, or provide background information. And she is allowed little desire, even as the rest of her family is granted a multitude of sexual explorations over the course of four seasons. When she climaxes in a bathtub in season two, as Maura pleasures her with her hand, it feels shocking, because heretofore her sexuality has been barely addressed. Yet that moment is focused more on Maura feeling obligated to Shelly’s libido, even slightly resenting it by the end. The scene tracks Maura in the mirror, looking at herself, knowing that she is over this dynamic. We know how Shelly’s body reacts — she has an orgasm, a big one — but we know how Maura feels.

I wondered at times if she was less interesting to the show’s creators because she had, compared to the rest of her family, such conventional notions of happiness. (What’s so interesting about a Jewish mother, anyway? Everything, I say.) She tells her son, Josh, that she wants him to be more present in her life early in season one. She spits, “I don’t want you to call me, I want you to be here.” But as I saw Shelly, she had just as far to go and grow as anyone else.

Shelly is given more agency when her boyfriend Buzz shows up toward the end of season two. Ponytailed, easygoing Buzz perhaps feels to Shelly like her last chance at happiness. What she has been taught — generationally, culturally — is to pair up, to be a part of a couple, and to surround yourself with family. For 13 episodes, they are happy together: He encourages her creatively, plans cruises for her family, and delights in pleasing her. That he is spending all her money and is kind of a con artist is a depressing reveal.

But I felt like I knew Shelly best in the scene where she discovers his betrayal. When Buzz invents a dead wife from his past, there’s a flicker in her eyes, a slight frown on her lips; her eyes gaze off as she does the math, registers disgust, and then resolves it. “We’re done, Buzzy,” she says with a dismissive hand and a wry laugh. “I could accept you being broke, I could accept you being in debt to the U.S. government, but what I will not accept is being lied to. Never again.” The camera finally stays on her for a nice long stretch. We see multitudes.

Still, throughout the third season, she remains comic fodder, particularly in the subplot involving her one-woman show, “To Shel and Back,” presented as part of the prestigious “Temple Talk” series at her shul. “I have started to live the truth of my existence,” she says. “To really open up for the first time in my life.” And I want that for her, desperately — for her to emerge. I want for her what I want for every Jewish mother of a certain generation who was raised to abide by a certain set of rules. I want her to fly.

A few episodes later, though, her evolution is treated again as a joke, when she announces at Maura’s birthday party, “I have transitioned too, I’m coming out, I’m reaching out. I’m a brand!” It feels like a cruel bit of mockery. By the fourth season, when she begins an improv class, I thought: Enough already.

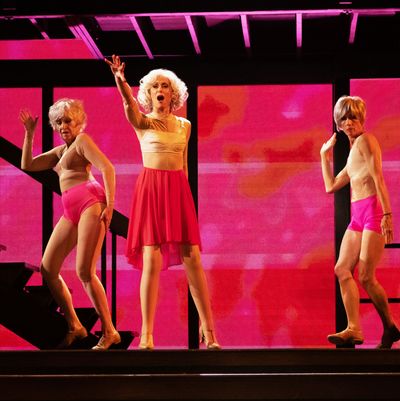

I always return to where I would have been fine with Transparent ending forever, at least when it comes to Shelly: the finale of season three. The Pfeffermans take the family cruise together, minus Buzz, and everyone treats Shelly like shit. She throws together a last-minute rendition of her one-woman show and finally has a moment of triumph, a moment to breathe: a stunning rendition of “One Hand in My Pocket.” Her wig taut and makeup subdued, she glitters in a jeweled jacket. There’s a hint of Carole Channing in her voice. Light’s graceful bones are perfectly lit. It’s a thoughtful, emotive performance, sincere as hell, but with panache, while her children watch first in fear and then delight. The scene is all hers, and what a relief it is for all of us.

At the end of season four, Shelly takes her maiden name back. She’s had a heavy-handed season, finally revealing her own childhood molestation to her family. Marriage and children had worn her down in her life — a feeling she’d expressed a few times over the course of the show. (Understandable with these kids, with that husband, with this world.) Now she’ll be a Lipkind again. She reclaims the version of Shelly “that was the last time I was truly myself,” she says. It gives me hope for her future and for the final, musical episode of the show. I still occasionally replay that scene of her singing “One Hand in My Pocket,” when she’s no longer just the mother or the wife. Who could she be if given half a shot? She’ll be fine, fine, fine.

More on Transparent

- Transparent Goes Out With One Last Crazy Dance

- The Transparent Finale Is an Expression of Everything the Show Was About

- Transparent’s Greatest Trans Legacy Is How Quickly It Grew Irrelevant