I hope you binged this episode back-to-back with the first one. I really and truly pray that you queued up Unbelievable and watched the first two episodes straight through without leaving for even a cup of tea or trip to the bathroom. It’s hard watching, for sure, especially for victims of sexual assault or rape. But these two episodes are designed to work in unison, a snugly fit-together yin and yang of police procedurals. Without the first, the second reads sticky sweet; without the second, the first is simply documentation of thoughtless neglect.

“Episode 2” picks up precisely where the last episode left off, with Marie leaning off the edge of a bridge, quivering and unsteady, perhaps about to hurl herself into the cold Washington water below. But something kicks in, and she hoists herself back over the barrier and onto the highway, just as Detective Parker formally closes her case. From there, we only dip back into her story periodically; most of this episode is taken over by an entirely new, though obviously connected, story of rape.

(It’s worth noting here that the chronology gets a little wonky if you aren’t paying close attention. Marie’s story is set in 2008. The rape that takes place this episode is set in 2011. So every time we shift back to Marie, we are also moving back three years in time.)

Merritt Wever, who deserves to have her name yelled in the sing-song Oprah voice whenever it is said, plays Detective Karen Duvall of the police department in Golden, Colorado, a victim’s advocate in every sense. She arrives on the scene of another apartment break-in and assault, this time of Amber Stevenson (Danielle Macdonald, of Dumplin’, who delivers a quietly potent performance), a college student. From the moment Duvall arrives on the scene, the tenor of her investigation is as starkly different from Detective Parker’s as possible.

Duvall’s first concern, beyond any procedure or evidence gathering, is to ask if Amber is okay, and to say it with true warmth in her voice. “Let me know if that changes,” she reassures Amber when she says she’s okay, pointing to the EMTs and reminding her, “They’re right here, and they’re here for you.” She brings Amber into the quiet and relative comfort of her car, and before launching into any sort of interrogation, begins, “If it’s alright with you, I’d like to ask you some questions.” Duvall explains exactly why she is asking tough questions, saying that recall is often better in the immediate aftermath of a crime. And most poignantly, she gets to know Amber a little bit as a human, inquiring about her studies, her boyfriend, life in a new place. Admittedly, I teared up — it was like watching advocacy in action. The language is like a gentle touch.

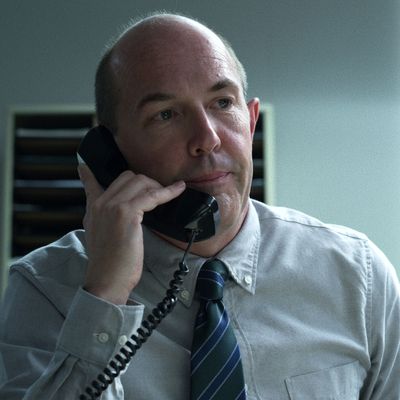

Of course, this scene is meant to be compared with Parker and his pockmarked partner’s thoughtless interactions with Marie. When the police entered her apartment, Marie was shivering with just a duvet tossed over her, and nobody inquired about her comfort. Parker gets all his background on Marie’s life from a file and then self-assuredly tells her he knows allllll about her without ever asking a question. Does Marie need a breather? Someone to hold her hand? An advocate assigned to her at the hospital? Nobody ever asks — she’s an information vessel, a means to solve the crime, not of much concern beyond that.

Back in the car, Duvall, with the most dulcet of voices — someone get Merritt Wever an NPR show, stat — offers a patient explanation of how rapes have three crime scenes: “the location, the attacker’s body, and the victim’s body.” What follows is an act of compassion so deep, and a scene so lovingly constructed, that it turns into a work of fine art. Duvall asks if, despite the fact that her rapist has required Amber to shower and scrub her face, she’d mind if the detective tries to gather some DNA from it. We’ve just seen a nurse briskly shine a light up Marie’s spread legs and a police officer bark at her foster mother not to touch anything, so this scene comes across even more starkly. Duvall takes two cotton swabs and slowly — in complete silence — runs them across Amber’s peach cheeks, her forehead, her chin, all the while lit from behind like a Dutch still life. Reader, I cried.

Duvall then walks Amber through her apartment and we begin to learn a little more. Her attacker peed a few times while he was there, meaning this was a long, protracted attack. He also put a comforter on Amber when she shivered, not wanting her to be cold. And creepily enough, he told her to put a dowel at the base of the sliding door he came in to rape her, offering a platitude, “You need to be more protective of yourself,” just after he himself has tortured her.

More information comes out via Duvall — that the rapist had been watching Amber, knew delicate things about her, like the fact that she talked to herself in the mirror every night before bed; he also waited until the evening after her boyfriend had left. He’d also previously been inside her apartment, where he stole a ribbon he eventually pulled from his backpack and used to tie her up — a move so similar to Marie’s shoelaces that it can only be intentional. Then he raped her for four hours at gunpoint. Four hours. Amber kept him talking the entire time, and managed to extract some small bits of helpful biographical information: He speaks four languages, visited a good number of international destinations with military bases on them. And he has a “theory of humanity” that sounds an awful lot like the sort of shit spewed on the dark web by pathetic, lonely little men who view themselves as the sad victims of wrathful women. He, with his infinite ego, thinks he’s a wolf, and that that is a high mark. After all that, she explains, Amber doesn’t believe this is his first rape.

It’s only after Duvall (and the audience) learn who Amber is as a person that the details of the crime begin to come out. There’s no forced repetition here, no telling the same story until we’re all sick and the victim is numb. Instead, after Duvall leaves her with a friend who has a hot bath ready, the story emerges. He woke her up with a gun in her face. Dressed her up “like a hooker and a little girl.” Stopped and started again eight times. Took pictures of her (with a flash, just like Marie’s rapist). And Amber has so much detail: his height, weight, that his pubic hair was shaved and he had holes in his sweatpants. That big birthmark on his left calf.

At times, Duvall’s halo shines a little too brightly (the story of the Isaiah quote in the car, for instance), but nonetheless she’s an artfully constructed character. There is some mystery to her (why all the nebulizer treatments and worry over her daughter’s cold?) and she rules with a leather-gloved iron fist (do NOT submit less than adequate crime-scene reports to her, officers). When she questions Amber’s neighbor about her head-lamp-wearing son — whom we can probably assume is somewhere on the autism spectrum — even her graceful handling prickles. The scenes with her husband, Max (Austin Hébert), a police officer in another town, offer up the best insights. When he asks whether she wants to talk about the case, that brief head shake contains multitudes, yet she can’t help herself from passing along the details. She’s emotionally unzipping, and the release pays off. Max has heard of a similar case in his precinct. The detective in charge might have some good information.

That detective is the El Camino–driving, tough-talking Grace Rasmussen (Toni Colette), who I hope lays off the rockabilly edge in upcoming episodes, because they’re oversold a wee bit — we get it, she’s badass. More of her and the backpack-wearing ditch-climber is coming, I’m sure. Nobody keeps Toni Colette in the El Camino.

Interspersed through all of this is Marie in the days after her own rape, snubbed by her friends, given mandatory check-ins and curfews from her counselors, hiding under her hood to keep the press outside her apartment complex from catching a glimpse. Amber certainly is not okay — no amount of mellow questioning from a well-trained and humane detective vanquishes the trauma of a rape. But Marie is in agony and alone, practically melting down when she looks down at the tray of suggestive roasting weenies she has to give to testy shoppers at the superstore where she works. The lie — about lying — is eating up the only stable sections of her already shaky existence. Her former foster father isn’t wrong, per se, when he points out that any blot on his character could undermine the work he does for other kids. But with his implication, “If you were to ever say anything like that about me …” he only confirms for Marie that this once safe haven is now just another stop on her trail of utter disappointment.