This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

The standoff between Bong Joon-ho and Harvey Weinstein over the U.S. cut of Snowpiercer had all the hallmarks of a scene the director might shoot himself. High drama. The Korean auteur versus the bullish American. Philosophical questions of artistic integrity in the time of mass consumption. Gallows humor.

Snowpiercer is a unique hybrid. It looks like a slick Hollywood action movie with revolutionary themes, depicting a class rebellion set in a sci-fi dystopia led by none other than Captain America himself, Chris Evans. But despite its blockbuster appeal, Snowpiercer languished in limbo in the U.S. The Weinstein Company bought the distribution rights in 2012, but instead of giving the film an immediate release date, Weinstein demanded changes. He wanted to cut 25 minutes. He wanted more action, “more Chris Evans.”

“It was a doomed encounter,” Bong tells me over breakfast one morning in Los Angeles. “I’m someone who until that point had only ever released the ‘director’s cut’ of my films. I’ve never done an edit I didn’t want to do.” And yet, he says, “Weinstein’s nickname is ‘Harvey Scissorhands,’ and he took such pride in his edit of the film. I am so proud of my edit!” Bong is a commanding presence, six feet tall and honey-bear shaped. He’s a mesmeric storyteller with killer comic timing, and he does a bombastic Weinstein impression — all hot air and hand gestures — punctuated by his wild, authorial hair.

Bong remembers one fateful meeting in Tribeca when he and Weinstein watched the movie together. “Wow, you are a genius,” he would say. “Let’s cut out the dialogue.”

Bong was at a loss: Cutting 25 minutes felt like taking out a major organ. Without the dialogue, the movie became incoherent; character motivation made no sense. That day, he managed to save one scene, the moment when a train guard guts a fish in front of the rebels as a show of intimidation. Bong and his cinematographer loved that shot. “Harvey hated it. Why fish? We need action!” Bong remembers. “I had a headache in that moment: What do I do? So suddenly, I said, ‘Harvey, this shot means something to me.’ ”

“Oh, Bong? What?” Bong-as-Harvey booms.

“It’s something personal,” Bong replies. “My father was a fisherman. I’m dedicating this shot to my father.”

Weinstein relents immediately: “You should have said something earlier, Bong! Family is the most important. You have the shot.”

“I said, ‘Thank you,’” Bong says, laughing. “It was a fucking lie. My father was not a fisherman.”

Still, the disagreement dragged on for months. Weinstein showed his edit to a test audience of about 250 in Paramus, New Jersey, at a giant multiplex that reminded Bong of Kevin Smith’s Mallrats. Bong thought for sure the reaction scores would vindicate him. And indeed, with so much of the dialogue excised, viewers felt lost and gave the film low marks. “On the inside, I was happy that the scores were bad,” he says. “But Weinstein comes out and goes, ‘Bong! Yeah, the score is very bad. Let’s cut out more.’”

“The whole thing was like a black comedy,” he continues. “If this was someone else’s movie and you were making a documentary of the situation, it would be really funny. Unfortunately, it was my movie.”

If it had come down to it, and Weinstein’s cut been released, Bong says he would have taken his name off the movie. But eventually the director prevailed. The distribution contract allowed him to show the original version to another test audience in Pasadena, California, where it played to much higher scores. Meanwhile, news of the conflict had leaked to the press, rallying cinephiles and the film’s stars, including John Hurt and Tilda Swinton, who wanted to see Bong’s version preserved. Weinstein backed down with a compromise: He kicked the movie down to the company’s independent arm, Radius. Instead of a wide release, it got a limited one. “Maybe for [Weinstein], it was some kind of punishment to a filmmaker who doesn’t do what he wants,” says Bong. “But for me, we were all very happy. Yeah! Director’s cut!”

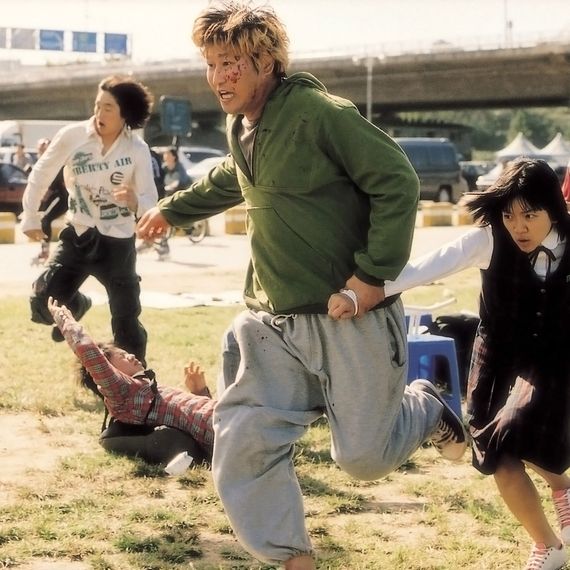

To a viewer familiar with Bong’s work, the metatext in the conflict is unmistakable. His films often center on underdogs fighting against authoritarian forces. In his 2006 breakout movie, The Host, a bickering Korean family finds itself battling a giant river monster born of American malfeasance: A U.S. military official orders a Korean lackey to pour hundreds of bottles of formaldehyde directly down the drain (an actual incident that occurred in Seoul in 2000), thereby creating a beast that terrorizes the city of Seoul (that part didn’t happen). The movie is an obvious metaphor for the global superpower that has often bullied and eaten up smaller countries like Korea.

In Okja, Bong’s follow-up to Snowpiercer, the protagonist is a young Korean girl from the countryside trying to save her pet super-pig from the grip of a multinational corporation. Bong slipped in an inside joke about the whole Weinstein ordeal, setting the final slaughterhouse scene in Paramus. After all, he felt a little like Okja, the titular pig, going from Korea to New York only to get dragged all the way to Paramus in order to get sliced and diced for mass consumption. But as the story would have it, both the pig and the movie survived intact.

Bong and I are heading west in a car toward his hotel in Beverly Hills. He’s in the middle of the North American festival circuit, where he’s been showing his new film, Parasite; he just arrived from Telluride the night before, and he’ll be heading off to Toronto in a few days. He has a “tastemaker screening” later tonight. “It’s the same in any country: Korea, Japan,” Bong says in Korean. “You know, doing preview screenings for movie people.”

Of course, we are dancing around his journey into the carnival that is an Academy Awards campaign, which seems to mildly amuse him from a distance. I ask what he thinks of the fact that no Korean film has ever been nominated for an Oscar despite the country’s outsize influence on cinema in the past two decades. “It’s a little strange, but it’s not a big deal,” he says, shrugging. “The Oscars are not an international film festival. They’re very local.”

Still, it’s hard not to feel that Bong could make (local) history. In a post-Roma world, maybe Parasite doesn’t get just Best International Film but Best Picture and Best Director nominations, too. Bong has already had a brilliant year: At the Cannes Film Festival this spring, he became the first Korean director to win the Palme d’Or, in a unanimous jury decision. The Korean press was rapturous upon his return. “Normally, people don’t care about film festivals. But I guess people really seem to focus on first place,” he says. He and Parasite star Song Kang-ho were greeted at Incheon airport as if they were the K-Pop group BTS. “It was an Olympic-gold-medal kind of feeling,” he says. “It was very awkward in the airport. Super awkward.”

The director has been a household name in South Korea ever since The Host, which became an instant blockbuster and the highest-grossing movie in the country’s history at the time. Snowpiercer broadened his scope, allowing him to think more globally. Then came Okja — at a cost of $57 million, Bong’s biggest-budget film to date — which he made with Netflix because it gave him complete creative control. After the experience with Weinstein, he wanted to ensure that every contract stipulated he have final-cut approval. Netflix didn’t balk at any of his demands. “Other studios were like, ‘Are you really going to film a little kid going inside of a slaughterhouse?’ ” Bong says. “Only Netflix guaranteed 100 percent approval of everything to me: the final cut and the rating.”

Parasite is smaller in scale but feels like the work of a master filmmaker evolving into a new stage, maintaining many of his signature moves — spectacular visuals, an uncanny sense of dread, and a dark, wry sense of humor — while compressing them into a two-hour thriller. At the outset, it’s a black comedy about class differences well suited to our season of scams. It follows the Kim family, who live in a half-basement apartment where the only sunlight trickles in from a narrow window near the ceiling. They catch a break when the eldest son, Ki-woo (Choi Woo-shik), is hired as an English tutor for the teenage daughter of the fabulously wealthy Park family. Ki-woo rebrands himself as “Kevin” and helps the rest of his family infiltrate the house. Everyone pretends to be someone they’re not: The sister (Park So-dam) becomes an “art therapist” for the youngest son, the father (played by Song) becomes the driver, and the mother (Jang Hye-jin) is hired as the housekeeper. The way Parasite’s story unfolds from there is like a magic trick. It alternately entertains and devastates, like a candy bar with a razor blade tucked inside.

“He’s just such a masterful storyteller, and on top of that, he knows how to have fun,” says the actor Steven Yeun, who worked with Bong on Okja. “He turns it up slightly Technicolor.” His films are rooted in genre conventions like action and horror that eventually give way to crushing realism. Memories of Murder is a scathing black comedy about police incompetence, The Host is an indictment of American hubris disguised as a monster movie, and Okja is a Totoro-esque escape story until the gears of factory farming begin to turn. In Parasite, the scam ultimately reveals something more insidious: that wealth is always built upon poverty and that the two are locked in a constant struggle. The poor wish to be rich, and in order for someone to be rich, someone else must be poor.

Bong’s work reflects anxieties he feels every day — about the climate crisis, the widening income gap. “My films generally seem to have three components: fear, anxiety, and a kekeke sense of humor,” he says, using the Korean equivalent of “ha-ha.” “Humor comes from anxiety, too,” he adds. “At least when we laugh, there’s a feeling that we’re overcoming some kind of horror.” In his view, our world is already a dystopia, and all tragedy and comedy flows from this fact.

Parasite, in particular, hits a nerve, tapping into the persistent feeling that we are on the brink of social collapse. “The true horror and fear of Parasite isn’t just about how the present-day situation is bad but that it will only continue to get worse,” he says. “That’s my own fear in my life. I’m 50 now, so I’m going to die in about 30 years. My son is 23 now. When he reaches middle age, after I die, will it get better? I don’t know. I’m not so hopeful. Still, we have to try to live happily. We can’t cry every day.” (He’s surprisingly sanguine about all of this.)

It’s perhaps because Parasite is such a distinctly Korean film that it resonates so widely. The trials and exigencies of modern Korean history — Japanese colonialism, the Korean War, military dictatorship — have given an entire generation of filmmakers like Lee Chang-dong (Burning), Park Chan-wook (Oldboy), and Bong a sense of breathtaking urgency. Korean filmmaking feels prescient today because of its own, recent entanglements with authoritarianism and poverty. It is less that Korean films have caught up with modern times than that modern times have caught up with Korean cinema.

“Okja, Snowpiercer, Parasite, they’re all stories about capitalism,” Bong says. “Before it’s a massive, sociological term, capitalism is just our lives.”

Bong was born in 1969, the youngest of four, in the southeastern city of Daegu, when South Korea was under the rule of a military dictatorship. His family’s house was near a U.S. military base, and some of his earliest memories are of watching American soldiers passing overhead in low-flying helicopters while the kids yelled what English they knew at them: “Tom! James! Hello, gum joo-so!” meaning “Give us some gum!” “The kids would shout any kind of name, and the American soldiers would wave their hands back,” he says. “I don’t mean to invoke the Korean War image of crying children, but those kids existed. The country was quite poor.”

Bong’s father was a graphic and industrial designer and professor. His mother worked as a housewife; her father had been an esteemed novelist during the Japanese colonial period. Bong never met him, though. The family was separated after the Korean War, and his maternal grandfather lived out the rest of his life above the 38th parallel in Pyongyang, North Korea. His mother’s sister lived up there, too. The siblings didn’t see each other again for 56 years, until they were reunited during one of the televised events in 2006 that brought together divided families. “Fifty-six years,” he says. “Totally fucking crazy.”

He gazes out the car window, recalling his first visit to L.A. more than a decade ago while on a press tour for The Host. “At the time, I felt the city looked very strange,” he says dreamily. It was so flat and wide, without the verticality and density that define cities like Seoul. “Everything is very … scattered,” he says in English. He speaks with unusual precision, as non-native speakers often do. “I cannot imagine what is the borderline of the city. I always want to know the borderline — it’s my personal problem.”

Bong went to college to study sociology at Yonsei University in Seoul’s Sinchon neighborhood in 1988, which was a time of political upheaval. “Every week, there was a demonstration in the university,” he says. Just the year before, South Korea had hit a tipping point in its ongoing fight for democracy. News broke that the police had tortured a student to death, galvanizing nationwide mass protests that forced democratic elections. College campuses were regular battlegrounds where students demonstrated for the expansion of democratic rights, labor unions, and reunification with North Korea. By the time Bong graduated from college in 1995, South Korea was experiencing its first spasms of democracy.

“We hated going to class,” he recalls. “Every day was the same: protest during the day, drink at night. Except for a few people, we didn’t have much faith in the professors at the time. So we formed study groups of our own covering politics, aesthetics, history. We’d drink until late at night, talking and debating.” He adds, “I’m not the kind of person who likes to be stuck in a group, so even while we were protesting, I would leave and go watch a movie. The lead organizers probably thought I was a bad activist.”

During demonstrations, the protesters threw rocks; the riot police threw rocks back and shot tear-gas canisters from cannons. Bong, along with everyone in his generation, made “humanitarian” Molotov cocktails from a mixture of paint thinner and water — they were visually explosive but less dangerous than those made with gasoline. “The other side were young kids like us who got conscripted into the military and sent out here, so we didn’t actually want to injure them,” he says. “Still, both sides were incredibly violent. It was a really dangerous time.”

Clouds of tear gas were a near-daily presence during Bong’s first two years on campus. “It was a very traumatic smell. It’s impossible to describe: nauseating, stinging, hot,” he says. “It’s strange, sometimes I smell it in my dreams. Usually dreams are images, but I sometimes have this sensation of smelling it. It’s really horrible, but I guess that’s the way it would be.”

In The Host, there is a machine that pours out a tear-gas-like substance called Agent Yellow to disperse protesters. The protagonists fight back with debris and Molotov cocktails in a scene clearly plucked from the director’s activist days. But while his films often have a radical impulse, they’re not didactic. “Song Kang-ho’s character in The Host has no direct relationship with America,” Bong explains. “He’s just a kind of dumb guy who runs a kiosk on the Han River.” His characters are typically uninterested in politics but get swept up in machinery much larger than them: global capitalism, governmental infrastructure, authoritarian forces.

We pull up to the Four Seasons, where a fleet of bellhops swarms the car to open the door for us. Just through the hotel entrance, a saleswoman is standing outside a small, glass-walled parfumerie. She hands Bong a sample of Krigler’s Sierra Vista cologne, which she describes as a “sexy scent” of cedarwood and jasmine. He takes a sniff. “It’s better than tear gas,” he says, laughing.

In 1992, Bong returned from two years of mandatory military service for his junior year of college. South Korea was in the throes of transformation. Censorship laws had relaxed, and unofficial French-style cinematheques were cropping up. The pop group Seo Taiji and Boys debuted, writing lyrics that were increasingly critical of conservative aspects of Korean culture. Film magazines sprang up, and a critic culture rose with them. “There was a weird explosion of pop culture,” Bong remembers.

Back on campus, he co-founded a cinema club called Yellow Door (“Very stupid name. The door for the group was yellow”) with students from neighboring schools like Hongik University, Ewha Womans University, and Sogang University. “We watched movies every day, analyzed them, wrote treatments,” he recalls. That’s when he made his first films, including a stop-motion short, Looking for Paradise, about a gorilla trying to escape imprisonment, and a 16-mm. short called White Man (Baeksaekin). I tell him I’ve had difficulty tracking down the latter. “Please don’t see it,” he pleads, after disclosing it’s an Easter egg on the Korean DVD release of Memories of Murder. “It’s a super-stupid, fucking boring film. It’s just terrible.”

Park Chan-wook, whose company, Moho Film, produced Snowpiercer, doesn’t remember it that way. It was the early ’90s, and he was working on an independent film, when a crew member called him and said, “I have finally found a short film that will satisfy your odd taste in movies.” Park watched White Man and says he “was instantly mesmerized by the film’s grotesque sense of humor.”

But not until Bong’s second feature, Memories of Murder, did his visual style begin to gel. In another life, he would have been a comic-book artist. Bong meticulously storyboards everything he shoots, and his movies look like individual frames come to life. He sketched out every scene for Parasite and Memories of Murder himself — complete with dialogue — and for films with bigger visual effects, like Okja and Snowpiercer, he worked with an artist. “He gave us storyboards that were fully bound books,” says Yeun of his experience acting in Okja. “They look like mangas, where you’re just like, Oh, this is the movie.”

Yeun describes the director as a “human animator.” He recalls how, on set, Bong would show him a shot with stand-ins so he could picture the composition before stepping into the frame himself. “Some people get jarred by that because they don’t like being told where to stand. But when you see the frame, you’re like, I know what we’re achieving here,” Yeun says. “You feel like a color.”

Tilda Swinton, who plays the colorful villain in both Okja and Snowpiercer, felt similarly. “Not having any particular process myself, I find this method peculiarly liberating. It frees us all to fill the frame, albeit within precise boundaries, with energy and a kind of quick-bursting freshness,” she writes in an email, emphasizing that this method still gives actors plenty of agency. “Director Bong is perpetually up for being entertained. It is a great feeling to amuse him.”

“It makes me less anxious,” Bong says of his process. “Without a storyboard on set in the morning, it’s like those nightmares where you’re in the middle of Manhattan just wearing your underwear. If you have a storyboard, it feels like you’re walking outside in clean, comfortable clothes.”

Perhaps most unconventionally, he doesn’t shoot coverage — that is, multiple shots from various angles and perspectives that get edited together later. Instead, he shoots exactly what he imagines, editing on set as he goes. “That process allows him to fully control what the cut is going to be, and the result ends up being very original,” says Kevin Thompson, the production designer for Okja. “He’s not getting more than he needs.” Bong finds it more efficient because everything about a shot has already been decided, so the cast and crew don’t have to repeat the same thing over and over from different perspectives. They can harness all their energies and focus on the task at hand.

Bong’s films often take years to plan (he first thought of the idea for Parasite in 2013) and require a complex wizardry of digital and practical effects. The luxe modernist house owned by the Parks in Parasite looks deceptively simple in its elegance, but it’s one of Bong’s most intricate creations yet. “On a fundamental level, if the structure of the house isn’t correct, the story doesn’t work,” he says. It was a technical puzzle: The first floor and private front yard were built on an empty outdoor lot in Jeonju, with a green screen placed on top where the second floor would eventually be digitally inserted. The other rooms of the house were built on separate soundstages. “There are nearly 480 visual-effects shots, but we can never feel it in the movie,” he says. “They’re invisible.”

We first experience the Park house as the Kims do, luxuriating in the clean, sleek lines and modern furnishings. It’s open, airy, and transparent, a private oasis away from the cramped and dingy space they live in. Eventually, the house opens up like an elaborate jewel box, with plot elements that hinge on the architecture: hiding, eavesdropping, scheming. More than a house, it becomes a map of class psychology and the resentment that simmers beneath the surface.

Bong Joon-ho is in his element poking around the Hollyhock House on Hollywood Boulevard, which was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright a century ago. We visit the historic building on his last day in L.A. He’s wanted to come here since the late actor Scott Wilson pointed it out to him on a drive. Bong wanders the space, politely pushing boundaries: He tests locked doors and pokes his head down into a basement that has been roped off from visitors. He wonders what the second floor is like. At this moment, he’s asking one of the docents if we can shut the house’s front doors — two massive concrete slabs weighing half a ton with hidden locks. The docent grimaces and agrees to shut one.

“Wow, it feels like the extension of a wall,” Bong says, marveling at the closed door. “Suddenly, it reminds me of the dialogue of Song Kang-ho in Snowpiercer, do you remember? Song Kang-ho said everybody thinks this is a wall, but actually this is a door, and then they explode it and go out. If we erase the borderline between the door and the wall …”

We quietly pad through the house until we reach a room in the corner — a small, sunny conservatory free of any furnishings. He takes a seat in the middle of the floor with a delighted smile. “Should we lie down?” Bong asks. He laughs and gets up, moving toward the library, which is stocked with children’s books. He points at the bookcase flanking the right side and giggles. “Push and open it. There’s a door behind it.”

As dark as Bong’s films get, they never lose their sense of play. At times, the jokes are mischievous references the viewer might not catch, like setting the slaughterhouse in Paramus, or elaborate visual gags. In Okja, for instance, a group of top executives huddle in a situation room to discuss how to deal with the super-pig; the shot is a meticulous re-creation of the famous Obama-era photo in which the president, Hillary Clinton, and other officials are gathered to witness the assassination of Osama bin Laden. “They’re all watching this pig cause a commotion with these really serious expressions,” he says, tickled.

Other times, it’s a love of hyperbole — like the family wailing over a death in The Host or Jake Gyllenhaal’s insanely over-the-top performance in Okja. Bong likes to have at least one toe across the line at all times. “Sometimes he would challenge me,” says Kelly Masterson, who co-wrote the script for Snowpiercer. “He’d be like, ‘This should be funny. I don’t know what, but it should be funny.’ ” He recalls writing a line for a scene in which the wizened rebel leader, Gilliam (Hurt), advises Curtis (Evans) to “cut out his tongue before he can talk to you” when he meets the train’s creator, Wilford (Ed Harris). Bong suggested they amend the line to “Cut out his tongue and eat it.” “Which is sort of cannibalism,” says Masterson, laughing. “I was just so horrified by that. But he thought it was funny. He would say something like that, and then he would giggle.”

For now, Bong doesn’t plan on doing another big-budget film like Snowpiercer or Okja. (He’s currently at work on a “slightly scary” Korean film inspired by a news event and an English-language production.) He prefers the size of a movie like Parasite because it allows him to achieve the specificity of his vision.

“You know how when you were little, you would use a magnifying glass to gather the sunlight into one point and burn a piece of paper?” he explains by way of metaphor. “Parasite was like taking a camera lens and gathering all of my concentration and focusing it in on one spot. When the scale is really grand, a bigger budget feels like a handicap. Your energy gets scattered.”

He adds, “And isn’t the smell of burning paper really nice?”

We stand in the loggia, a transitional space between the living room and the garden, looking out into the enclosed courtyard. The brightly lit grass vividly calls to mind one of the final shots from Parasite: the green, sun-drenched front lawn, glimmering with the promise of the freedom money can provide. The hope in Bong’s movies often springs from this longing: to find a little patch of sunlight to call your own, if only for a moment. The optimism almost makes it crueler.

We head toward the dining room of the house, which is furnished with a hexagonal wooden table and a fabric light fixture above.

“If there were a fire, this would burn really easily,” Bong says with a smile. “Of course, one hopes something like that doesn’t happen.”

*A version of this article appears in the September 30, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!