One of the primary through lines of Hannah Gadsby’s Emmy-winning special, Nanette, was an argument against comedy. Gadsby might stop doing stand-up, she tells her audience, because comedy had been a way for Gadsby to tell a story about herself that crystallized a traumatic experience at its point of trauma, preventing her from coming to terms with it. “You learn from the part of the story you focus on,” Gadsby says. Because comedy requires tension, and because happy endings are inherently unfunny as Gadsby understands them, comedy was antithetical to telling a healthy story about herself. Her own comedy was a form of self-harm.

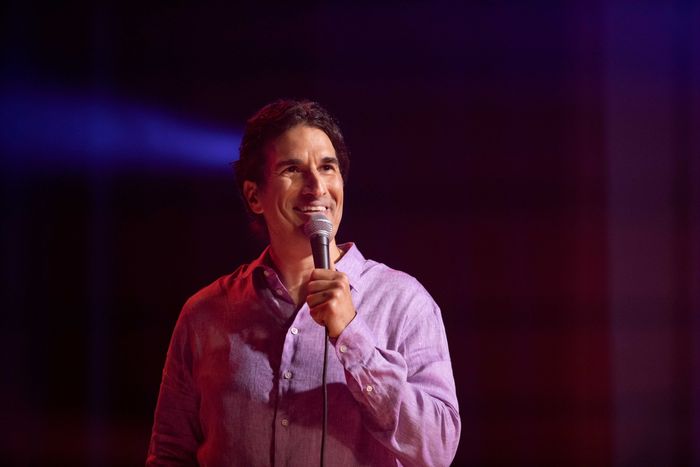

It is incredibly unfair to begin a review of Gary Gulman’s new HBO special, The Great Depresh, with a paragraph about someone else’s comedy special, especially when it’s a very famous comedy special that’s also been something of a third rail in comedy discussions. But I’m doing it because Gadsby’s special is an argument that comedy is inherently abusive, and often self-abusive, especially when the material hinges on the comic’s personal experience of pain. The Great Depresh is precisely that: an hour-long stand-up set (interspersed with segments of documentary footage) that focuses on moments of great pain in Gulman’s life. It also has a pretty happy ending. By the argument of Nanette, none of Gulman’s The Great Depresh should be funny. Except it really, really is.

The Great Depresh is also sad and serious and dark, and it involves a few long periods in which Gulman sustains the thread of his story without reaching for moments of laughter. He lingers on some of the lowest moments of his life. He talks about contemplating suicide. He talks about thinking his comedy career was over. He talks about his sense of shame. Some of the most painful parts come in the material about his childhood and young adulthood, when his depression was untreated and unrecognized by those closest to him. In one sequence, Gulman talks onstage about how he knows his depression began when he was very young, and then the special cuts to recent footage of Gulman with his mother as they look at photos from when he was little. The director, Michael Bonfiglio, off-screen, asks Gulman’s mother whether she thinks he was depressed as a kid. “No,” she tells him. “Absolutely not. A happier kid you couldn’t find, always had a smile on his face.”

That’s the point, of course — young Gulman’s happiness was a persuasive performance, but it was not true. It was a story he was telling, a happy story, and it was damaging because it was so happy and so far from his lived experience. The Great Depresh is a story, too — one that’s much sadder and more bleak. Only Gulman could say whether the experience of telling it over and over each night as he polished the set was a healthier one than the false happy version, but the experience of watching it is a good one. It’s affirming without being trite, and it’s warm without being simplistic. The ending of the special is an acknowledgement that yes, he is better now, but also that he’s not cured. Things will still be hard. Life, as Gulman explains with a grimace, is “every single day.”

And he does do some of the self-deprecating humor that Gadsby finds so personally troubling, especially in the beginning. When he talks about his wife recalling a time when all he did was sleep and cry, he retorts, “I also watched Better Call Saul.” He describes moments from his depression that are not exactly flattering. But the impulse underneath those sequences isn’t self-flagellation or self-loathing; it’s generosity. Even in the bleakest, darkest bits — a joke about how his hatred of essay writing probably saved him from committing suicide more than once, because it would’ve required him to compose a suicide note — the self-deprecation feels more like relief than it does pain, because his comedy encompasses that moment of trauma, acknowledges it, and then defuses its power by making it one part of a much longer story.

It’s a very personal special, rooted in Gulman’s life and in the story of his last several years. But one of the smartest things The Great Depresh does is connect his experience with bigger generational critiques. Notably, for a nearly 50-year-old white guy doing comedy today, Gulman has no patience for the brand of millennial bashing that has marked many other comics in his cohort, the fragile masculinity and unthinking longing for a bygone era that’s led too many comics to insist, whiningly, on their right to ignore things like political correctness or how other people feel. Instead, Gulman uses his own childhood to skewer the blithe damage done by a boomer culture that tolerated bullying; insisted on a narrow, impossible vision of what good manhood looked like; and, as Gulman hilariously points out, insisted on wide-scale childhood dehydration. The special is an implicit celebration of the fact that even though life itself is still an often excruciating thing that has to be endured again every single morning, some things have gotten better.

There’s a joke in the middle of the special that’s part of Gulman’s run on how much has changed, not just for himself but for huge cultural assumptions about childhood. It’s a joke about the mass paranoia about child kidnappings in the early ’80s, and in it, Gulman imagines himself as a little boy eating a peanut butter and matzo sandwich, staring at the face of a kidnapped child on the back of a milk carton. “I’m sorry, I’m so sorry,” he describes his kid self thinking, “but what am I supposed to do about it? I’m 6!” The surface of that joke, the funny part of it, is the absurdity of asking children to be the responsible parties, the bizarre assumption that kid detectives full of gumption were going to crack the case of a horrific crime. But the inside of that joke, the part that resonates afterward, is the happy relief that it was an absurd, sad thing that’s now past. It’s a joke that relies on the audience’s understanding that change was good, that the story got better. It’s a demonstration of what the heart of The Great Depresh is about: generosity and warmth and yes, self-deprecation, but also relief that the story Gulman is telling can be one with an upward arc.

The Great Depresh is also proof of the idea that a story about getting better — a story about one guy recovering and an entire culture of mental health-related shame diminishing — can also be a funny story. A special like Nanette was a powerful reckoning with how Gadsby needed to talk about herself, but it was also tilted at a universal truth about the necessary wounds comedy inflicts as a form, and I could not escape the sense that The Great Depresh was a demonstration of how that just doesn’t have to be the case.