I love space movies, especially those that darkly ponder the human experience. But lately, they have started to gently warp my brain. Watching them, I’ve begun to wonder things like: Are you really a dad if you have not ventured sadly into space, leaving your children behind, blinking forlornly into the sun? Are you really a son if you have not followed your sad dad into space, bravely heading into the unknown universe to complete his life’s mission rather than grapple with the most tender parts of your human nature? Can you rightly call yourself a daughter if your sad dad has not left you totally alone on the Earth while he saves the world? Can you call yourself an astronaut if you have not exploited space as a metaphor for your own personal failings?

2019 alone has blessed us with not one but two Sad Dad Space Movies. In Ad Astra, Brad Pitt plays Roy, a sad man chasing after his sad dad, who went to space several decades ago and disappeared and might now be accidentally destroying the planet. In High Life, Robert Pattinson is a sad dad raising his daughter alone on an increasingly hopeless spaceship with a complimentary “fuckbox.” But it’s not just this year — our filmic history is rich with repressed men who must leave literal Earth to feel something. Everyone from Bruce Willis to Matthew McConaughey to Will Smith has played a mopey parent boppin’ around in zero-G. Liv Tyler and Chris Pratt and Jessica Chastain have all played the child left behind who feels a responsibility to carry on a father’s mission. Chris Pine has done two Sad Dad Space Movies!

What is it that draws the cinematically inclined back to this depressing well again and again? What is it about this particular story, and its metaphorical implications, that makes so many male filmmakers say, “Whoa, I should make a movie about a fuckin’ sad dad … and set it in space!” Is it about male-centric legacies and fatherly approval and the inevitable void these things create? Are all of the wormholes the sad dads have to travel through metaphors for the birth canal? Is it about dicks, somehow?

In an effort to understand the manly impulse to keep making this sort of movie over and over, behold: a taxonomy of Sad Dad Space Movies. By no means is this taxonomy a complete encyclopedia of all Sad Dad Space Movies ever made; instead, I’ve chosen a few representative films for each category and delved into their patterns and similarities. (Also, any movie where all of the characters are native to space and/or are, for all intents and purposes, “aliens,” doesn’t count, but we can all agree that, yes, Star Wars is about a sad dad.) So look melancholically out your window at the world below, open your clenched fist to reveal a little locket with your child’s photo in it, then throw that locket into the universe’s gaping maw and read on.

Dad Disappears Into Space and Kid Follows Him, Only to Discover That He Basically Sucks

The Trope: One of my personal favorite — and most regularly exploited — Sad Dad Space tropes involves a father disappearing completely into space while working on a very important space project that throws his lack of attachment to his own family into sharp relief. Eventually, his abandoned child — often at this point an adult himself and profoundly messed up — follows him into deep space, only to discover that his father is kind of a chode. At some point, both sad dad and sad child have the same realization: The ultimate daddy is space itself — cold, unknowable, infinitely alienating, floaty, scary.

Some Fun Examples: In Ad Astra, Brad’s sad dad abandons him as a youth, turning him into the type of person who says things like, “I will not rely on anyone or anything.” He is thusly incapable of loving Liv Tyler or of having even a little bit of fun looking like Brad Pitt. At one point, Donald Sutherland turns up and states, quite plainly, the subtext of the entire film: “We think your father might be hiding from us.” At another, Brad wrestles with a psychotic space ape, i.e., his own reckless human nature. Eventually, Brad follows his sad dad all the way to Neptune, where he has murdered all of his co-workers and defaced several National Geographic covers. His dad is not happy to see him and refuses to leave space. “I never cared about you or your mother or any of your small ideas,” he says. “I never once thought about home.” He and Brad perform a gentle space ballet in the shadow of Neptune before Brad generously allows him to float into deep space, where he will die alone. Brad, who has now learned that neither his dad nor space itself is God, returns home, cured of his daddy issues.

Furthermore, in Ava DuVernay’s A Wrinkle in Time, young protagonists Meg and her brother Charles Wallace travel through a tesseract to a distant planet called Uriel to reach their long-lost scientist dad, played by Chris Pine. Chris Pine is ostensibly a really good scientist, good enough to travel through time and space, but not good enough to leave once he gets there. His own children are forced to pick him up with the help of Oprah! Can you think of a worse waste of Oprah’s time than picking up somebody else’s dad from space?

There’s also a lot of Sad Daddy Shit in Guardians of the Galaxy — Gamora, you have my sympathies — but in my eyes the most significant Sad Dad situation belongs to Peter Quill (played by the absolute worst Chris, Chris Pratt). Abducted and raised by absolute jamokes, half-human Peter has no idea who his dad is; when he eventually meets the guy, it’s revealed, in a rampant abuse of Freudian metatext, that his name is Ego. His name should make it readily apparent, but yeah, Ego sucks. He has fathered thousands of kids to keep his seed going, Jeffrey Epstein style, and occasionally murders them. He gives the mother of his child a brain tumor so that he can continue conquering the cosmos. When he finally meets his son, he says incredible Sad Dad in Space things like, “I don’t know where I came from exactly. First thing I remember is flickering. Adrift in the cosmos utterly and entirely alone.” Ultimately, he sucks so badly that his own son needs to kill him. (This is its own subgenre, really, similarly played out in Star Wars.)

Good Dad Dies (in Space, or Not in Space!), Inspiring Child to Go to Space (Either Way)

The Trope: Juuust variant enough from “sad dad disappears in space,” this trope centers instead on “sad dad disappears in time,” and follows the child who’s inspired by their perfect sad dad’s untimely death. Space is the void is death, etcetera, etcetera. These movies usually begin with shots demonstrating the things sad dad did to inspire in his child a lust for adventure and an insatiable curiosity regarding the unknown: Show them space through a telescope; make sweeping statements about the incomprehensibility of the universe; say some mysterious shit and then walk calmly into another room and die. Subsequently, the child becomes singularly obsessed with traveling to space, perhaps in hope that once there, he or she will discover the meaning of the universe and understand why his or her perfect dad had to die. The ultimate motive, though, is to finish what the dad started: You can’t get your sad dad’s approval if he’s dead, but by completing his mission, you can sort of assume that you’d have it, which is enough if you’re also in a lot of therapy. Which brings us to …

Some Fun Examples: Contact, a truly incredible film, stars Jodie Foster in a series of great scrunchies as Ellie Arroway, a scientist who learned to love the cosmos as a young kid thanks to her vaguely sad dad (it’s mostly in the eyes). Ellie’s dad teaches her to use radios to talk to strange men in far-away places and shows her meteor showers in the night sky and sums up the likelihood of intelligent life on other planets as follows: “If it is just us, this seems like an awful waste of space.” After he collapses from a heart attack, Ellie is determined to figure out if there is, indeed, life on other planets. The movie, based on a book by Carl Sagan, is ultimately about the interplay between science and faith and the ability to love to travel across time and space; all of these ideas are demonstrated most beautifully by a scene in which Ellie travels to a far-away galaxy and speaks with a simulacrum of her dad on a simulacrum of a beach she painted as a child. Her “dad” tells her that he’s part of an alien race that has been slowly revealing itself to other species for billions of years: “The only thing that makes the emptiness bearable is each other,” he says. Everyone, including you, the viewer, cries uncontrollably. When Ellie returns to Earth, nobody believes her, because she doesn’t have any Instagram videos of it. But Contact ends happily anyway: Jodie Foster and Matthew McConaughey drive off into the sunset and a brief conversation between government officials reveals Ellie is the victim of a conspiracy coverup, i.e., aliens are real!

In the massive Chinese space hit The Wandering Earth, an astronaut named Liu Peiqiang attempts to save Earth from being scorched by the sun and has to leave his son, Liu Qi, behind for most of his childhood. Dad is supposed to come back, but we all know how that sort of promise unfolds. Just before he’s due to return, everything goes to shit onboard, and Liu Peiqiang must sacrifice himself by hurling his body into a lot of hot plasma in order to save the world. The film flashes forward and reveals that Liu Qi has now adopted his dad’s mission and is now in charge of saving the Earth. You love to see it.

J.J. Abrams’s Star Trek reboot opens in the midst of a crazy space battle, during which James T. Kirk is born to a strapping Chris Hemsworth. Star Trek puts the Sad Dad Death into hyperdrive: Chris Hemsworth dies immediately. Years pass, and a young Kirk, now a prolific barfighter on Earth, is convinced to join the Starfleet Academy. In a series of plot twists that I cannot be bothered to get into here, Kirk travels to space, where he saves himself and his fellow space friends a number of times. Soon, he is promoted to captain, though he does not grapple with his daddy issues in any sort of cathartic way.

(Some tangential films that nearly make it into this subgenre: Thor: Ragnarok, a reverse of the trope, in which Thor’s sad dad’s death inspires him to go to Earth; Solaris, in which George Clooney is haunted by the memory of his sad wife in space; Gravity, where Sandra Bullock is haunted by the memory of her dead daughter in space; and Arrival, where Amy Adams is haunted by the future memory of her dead daughter while speaking to aliens on Earth.)

Dad Leaves Child on Earth to Essentially Go Fuck Themselves

The Trope: In these films, the sad dad is the central figure, and their children are mere supporting players who are left on Earth like chumps. The point of the film is usually something along the lines of, “Sad dad makes the ultimate sacrifice to pave the road ahead for his children.” The sad dad can never fully enjoy space because he feels bad about leaving his kids behind, but not enough to, like, actually come back from space. Sometimes the kids turn out okay and toil away on the ground in an effort to bolster their fathers’ legacies. Sometimes they sit forlornly in a bathtub, playing idly with a floaty rocket-ship model as their sad mom bathes them. If the kid is a girl, there is a better chance that she won’t turn out all fucked up; the girl and her dad often share a love of space and that connection motivates her to become a spunky genius. But if the kid left behind is a boy, he usually take things extremely personally and turns out like Casey Affleck in Interstellar, making his kids breathe in toxic dust just to prove a point.

Some Fun Examples: The Ur-text “sad dad leaves child on Earth to essentially go fuck themselves” movie is Armageddon. This movie is also a study in “paternalism” in every sense of the word. No scene illustrates this further than the scene wherein driller-cum-astronaut Bruce Willis’s daughter, played by Liv Tyler, has sex with her driller-cum-astronaut boyfriend — who is, confusingly, both despised and beloved by her father — to the stirring sounds of her real-life dad Steven Tyler’s song about fucking. Liv: I am so sorry about the ’90s. Anyway, Bruce Willis leaves his daughter on Earth so he can go save the world by blowing himself up with a nuclear bomb inside an asteroid. But our girl takes it in stride! She cries a little bit, but mostly, she just sort of stands at NASA’s control center without causing any kind of additional interpersonal drama. This is even more impressive considering the following facts: All of her dad’s fellow oil drillers consider themselves to be her surrogate fathers and call themselves her “daddies” (Steve Buscemi’s character, for one, mentions that he taught her to use tampons as a teenager); Ben Affleck thinks of her dad as his surrogate dad, even though he is fucking her; as an intrepid reader told me recently, Liv’s own father once almost left her to go to space. There’s also this: When Bruce Willis is about to die, he turns to Ben Affleck and says, “You take care of my little girl now. That’s your job. I always thought of you as a son. Always. And I’d be damn proud to have you marry her.” And it’s important to add that, at the end of Armageddon, a mom hands her son a small model of a rocket ship.

I love Interstellar, but it is essentially a study in sad-dad clichés. Matthew McConaughey begins the film by leaving his two kids to go fuck themselves on a dying Earth, and later, he’s so sad about it that he breaks the time-space continuum to contact his daughter (and himself) via a bookshelf, begging himself not to leave. His daughter Murph, played by Jessica Chastain, handles the whole thing relatively well and becomes said spunky genius, à la Liv and Jodie Foster, but definitely has her fair share of, “If you’re going to leave, just GO!!!” moments. Which is fair, as we cannot lose sight of the fact that she is literally just gaslit by every man she trusts in this movie, over and over again, up until the point of her death: Her dad scoffs at her when she claims that there’s a ghost contacting her via her bookshelf; her lifelong mentor lies to her about an impossible physics equation; her brother Casey Affleck refuses to listen to her when she’s like, “My man, your kids are inhaling toxic dust, get the hell off this farm.”

The most sad dad part of the movie happens early on, when Matthew McConaughey tells a young Murph that, as a father, one is essentially “the ghost of their children’s future” (which he takes a little too literally later on). Or maybe it’s when a gentle robot tells McConaughey, “The only way man has ever gotten anywhere is by leaving something behind.” Or maybe it’s when a 50-something McConaughey has to watch his 90-something daughter die? I don’t know; this movie is sad as hell!! Jesus!

First Man, based on the true story of Neil Armstrong’s jaunt to the moon, takes sad dad in space to new heights, if you will (you will). Not only does Ryan Gosling have to watch his baby daughter die tragically of cancer, he must then leave the rest of his kids as he goes to the moon — who is the saddest dad of us all! Ryan deals with his sad-dad-ness by becoming totally dissociated from his loved ones and himself, which is a classic sad-dad coping mechanism. As David Edelstein writes in his review, the film is “full of scenes in which Armstrong is torn between his kids asking him to play and the papers on his lap. Those are the only times you see Armstrong’s fear. He sticks with the papers.” Sad dads in space: They love papers. But the most sad-dad moment of all happens near the end of the film, when Ryan reaches the moon: The very first thing he does is hurl his daughter’s bracelet into the void.

Child Goes to Space With Dad, Often to Disastrous Effect

The Trope: Sometimes, sad dads cannot bear to leave their offspring on the Earth, or some kind of catastrophic global event compels them to bring their kids into space. This never ends well. Sometimes the kid becomes a maniac (Zenon: Girl of the 21st Century); sometimes the kid presses the wrong space button and somebody ends up dying. Either way, nothing good ever comes of a kid and a dad being in space together — it’s unnatural, somehow, to have two members of the same family staring into the void simultaneously. How is space supposed to act as a metaphor for the unknowability of the universe if the person confronting that unknowability isn’t depressed and alone?

Some Fun Examples: In High Life, sad dad Robert Pattinson and his baby daughter are the only humans left alive on a space shuttle once designated for doing crazy experiments on convicts. Robert does his best to give his daughter a “normal” life — he has plants! — but as she gets older, and starts to get her period on things, he begins to realize that there’s no real hope for either of them. First of all, as I have mentioned, he is extremely sad. Secondly, there’s a weird undercurrent of “Are they gonna fuck?” Ultimately, Robert’s like, “Okay, uh, why don’t we go check out what’s going on outside of the space station? Just for fun.” The implication is that they both die, because it’s better to die than fuck each other. I’m really glad Claire Denis decided that they were gonna die instead of fuck.

After Earth was described by Vulture as “Will Smith’s love letter to Scientology,” which should be enough of an indicator that it is innately disastrous. Based on a story by Smith himself, the movie follows sad-dad Smith and his real-life sadson Jaden as they fight an alien race on the planet they fled to after Earth died. Jaden is mad at sad Will because he thinks it’s Will’s fault that his sister Zoë Kravitz died, and this is the central emotional conflict of the story. But After Earth gets into some real weird Scientology shit along the way: Will “audits” Jaden to help him overcome an early traumatic experience, leading him to be able to “level up” in military school; the aliens attacking them are activated by the “scent” of human emotion (help); and Jaden is only able to defeat the race when he turns off all of his feelings. Though the father-son duo is ultimately successful at the end, they’re both still Scientologists IRL and where is Shelly Miscavige???

Prometheus is perhaps the best example of how it’s a bad idea for dads and their kids to go to space together. An elderly CEO funds a mission to space that includes his daughter, then secretly hides himself aboard the ship in an attempt to figure out how to defeat death. Naturally, he and his daughter are both murdered. The movie concludes with the proliferation of an alien race hellbent on destroying humanity. If this sounds like we’re kind of just talking about Ad Astra again, you’re right; we’re a dozen pivots into this taxonomy, and we’ve barely left the Sad Dad parking lot.

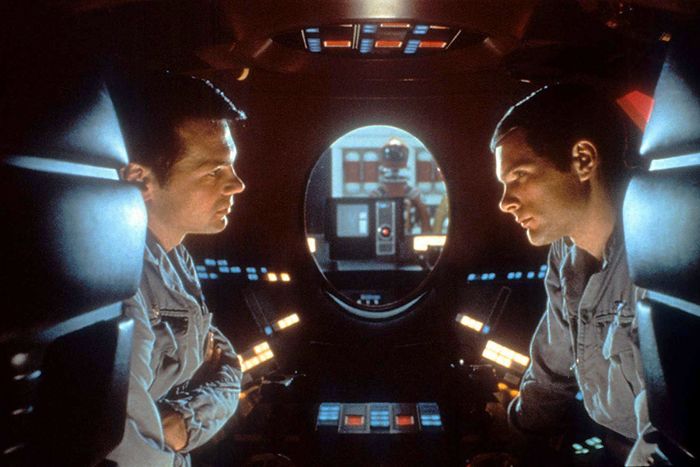

Man Goes to Space with Father-Figure Computer Who Murders All of His Co-Workers and Then Tries to Kill Him, But Eventually He Kills the Computer and Later Is Reborn As a Fancy Evolved Baby

This is what happens in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Which is further proof that, in essence, every space movie is about dads, daddies, being daddied, or failing at daddying.