It’s a movie about people sitting in rooms and talking, and its climax involves everyone calmly watching a television program. Michael Mann’s The Insider, which celebrates its 20th anniversary on November 5, is one of the most absorbing films I’ve ever seen — a tale of volatile passions and real, stomach-gnawing menace — and yet, whenever I attempt to describe it, people look like they’re ready to fall asleep. But maybe that too, curiously, speaks to its power: It’s about drab boardrooms and mundane offices — spaces filled with corporate doublespeak and legal minutiae — where people’s lives are destroyed.

The story does not, at first glance, seem like the stuff of high cinema. Based on real events that transpired in the mid-1990s, The Insider follows 60 Minutes producer Lowell Bergman (played by Al Pacino) as he tries to convince ex-tobacco industry scientist Jeffrey Wigand (Russell Crowe) to reveal that his former employer, Brown & Williamson, suppressed research about the addictive powers of nicotine. In order to do so, Wigand must break an ironclad nondisclosure agreement he signed with the company. After some machination, much of it involving an anti-tobacco lawsuit being brought about by the attorney general of Mississippi, Bergman finally gets the whistle-blower to sit for a 60 Minutes interview with legendary newsman Mike Wallace (Christopher Plummer) — but then has to fight his CBS colleagues, including both Wallace and 60 Minutes creator Don Hewitt (Philip Baker Hall), when the company, fearing a lawsuit that could derail their impending sale to Westinghouse Corporation, declines to air the segment and instead runs a toothless, abridged version of the story. Bergman goes on the warpath, using his connections elsewhere in the media to force CBS to air the full segment.

The Insider starts off as a movie about the lies of Big Tobacco, but then transforms, halfway through, into a whole other movie about the corporate control of media. It was a ripped-from-the-headlines story at the time — the events in question had occurred just several years earlier, and the emotions among the key figures were still so raw that they’d sometimes call the filmmakers and bitch them out — but it also captured unsettling truths about journalism that today seem chillingly prescient. And yes, it does involve a lot of talking.

“They called me once from the set and asked, ‘Do you do anything other than get on the phone?’” Bergman recalls. “‘We’re going to call this movie The Phone.’”

It was around the time Bergman and Mann were working on another film project together — “about a fascinatingly duplicitous, Sydney Greenstreet–esque, 350-pound Armenian arms merchant” named Sarkis Soghanalian, Mann says — that Bergman began sharing with the director his concerns about CBS management’s refusal to air a potentially incendiary 60 Minutes segment with Wigand. “I was one of maybe 20 people Lowell would call up and say, ‘You’ll never guess what happened today. I walked down the hall and passed Don Hewitt and he looked at me as if I didn’t exist,’ that sort of thing,” Mann says. After seeing the abridged version of the 60 Minutes piece about Wigand that aired in late 1995, Mann had a revelation. “My wife and I watched it, and I remember it vividly,” Mann says. “It just hit me like a bolt of lightning. I called Lowell and I said, ‘Forget Sarkis, man. What you’re going through — that’s a movie.’ Then I called my good friend Eric Roth and said, ‘Let’s write this thing.’”

Unlike with other films ostensibly based on real events, Mann and Roth didn’t have the option of embellishing the tale with Hollywoodized fake history. You see, The Insider was produced by Touchstone Pictures, a Disney subsidiary, and it dramatized recent events involving several other huge, rather litigious corporations, including CBS, which after all was a competitor to Disney-owned ABC. To avoid any potential lawsuits, the movie had to be rock solid when it came to accuracy. (If you read the Vanity Fair article on which The Insider is based, Marie Brenner’s “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” you might come away surprised at how much of the story made it into the finished film.) “Our writing was held to the same kind of standard that Lowell Bergman uses in journalism, which is that it wasn’t authentic unless it could be corroborated at least a couple of times,” Mann says. “Every line of description in the script was subject to the most rigorous kind of fact-checking.”

Roth, always a stickler for research, found himself going through acres of transcriptions and depositions, as well as Bergman’s extensive notes. Some of the individuals involved in the events cooperated with the filmmakers. Some did not. And then there was that third category: “Mike Wallace used to call and scream at me,” Roth says. “What, you believe this fucking Lowell Bergman? He would say all sorts of things, and I’d write it down and we’d put it in the script.” Mann too received phone calls from Wallace; he even recorded one and put some of what the veteran newsman said into the script. Of course, Wallace — who comes off as a complex, flawed character in the movie — would later slam The Insider for what he felt were inaccuracies. “Mike Wallace was heroic in some ways, but not in this instance,” Roth says. “Still, I wish more television journalists would be so hard-hitting with people like he was. He invented the hard interview and he was great at it.”

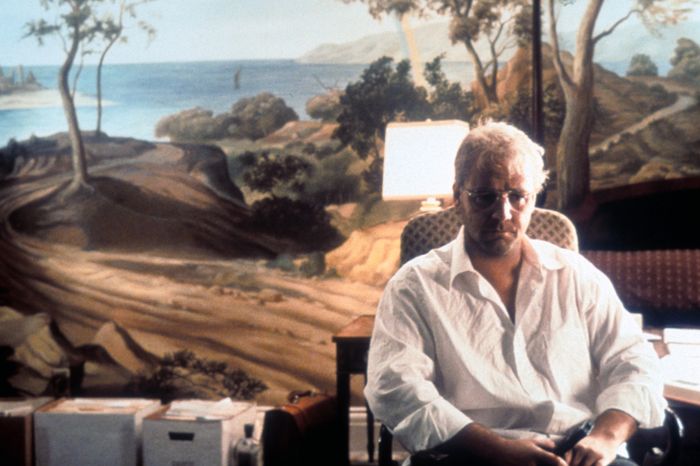

For Mann, the appeal of The Insider lay not so much in the particulars of the Wigand case, or even the behind-the-scenes drama at CBS, but the push-pull between two extreme, intense personalities: the repressed Wigand, a scientist who had betrayed his ideals and gone to work for a tobacco company, and the dogged Bergman, who felt he was realizing the radical ideals of his youth via investigative journalism. “What really motivated me was a real journey into the internal zones of these two people,” Mann says. “Lowell Bergman is unselfconscious and comfortable in his own skin. He is so centered. That’s at the core of his ability to find out and get what he needs. The other guy is living within well-architected, constructed simulacrums of a life that he inhabits only a part of. Jeffrey Wigand has put himself in a state of contradiction in relation to how he should be perceived in his own mind.”

You can sense traces of this in the film’s opening counterpoint. First, we see Bergman, blindfolded, being driven to a Hezbollah safe house in Lebanon where he will negotiate an interview with the organization’s leader — just another day in the life of a 60 Minutes producer. Then, we see Wigand at his office in Kentucky, quietly packing his things against a large window, behind which his colleagues are having a birthday party. Bergman is always aware of his constantly shifting, often dangerous surroundings, even when blindfolded; Wigand seems to be living in an aquarium, lost in his own world behind glass walls.

In some ways, it’s a dialectic similar to that of the director’s previous film, Heat, which pit calculating, disciplined expert thief Robert De Niro against intuitive veteran detective Pacino. In Heat, the protagonists were in constant opposition to each other, but their perspectives were equally balanced; you rooted for the robber to get away while simultaneously rooting for the cop to catch him. The characters in The Insider aren’t opponents, exactly, but their clashing personalities help drive the narrative. “If you take the whole story and have an X-ray of it, you would find that Wigand and Lowell are in direct opposition to each other throughout,” Mann says.

A fan of German Expressionism, Mann has always sought to capture his characters’ subjectivity; he wants us to see the world through their eyes, and to understand how their brains work. The Insider is replete with shots that are unusually close to the characters’ faces and shoulders and ears, as if trying to enter their heads. “We found a tall Frazier lens, made by an Australian guy to photograph insects,” recalls cinematographer Dante Spinotti (who also shot Heat, Last of the Mohicans, and Manhunter for Mann, and would later shoot Public Enemies). “Meaning you can really be close to somebody’s face — you can literally put something on the lens and focus on it.”

Mann’s style had progressed from the precise, graceful pictorialism of his early work, as the music-video elegance of movies like Thief and Manhunter gave way to something more ground-level, unhinged, and alive. “So much of The Insider was handheld,” says Spinotti. When the camera was on a tripod, or a dolly, he says, it was always on a shot bag, or a sand bag, “so that the operator always had this slight instability to the image.” Mann would continue in this direction in subsequent films. Following The Insider, he started experimenting with digital video, finding in the low-lit intimacy of handheld DV cameras an unprecedented, you-are-there quality.

The expressive energy of the frantic camerawork provided a key to unlocking The Insider’s drama. It would have been easy for the film to play out as a sober procedural, but by entering his characters’ minds, Mann turns it into something far more operatic. Consider an early scene when Wigand is called into talk to his former employer after his first meeting with Bergman. He sits in the office of molasses-voiced Brown & Williamson CEO Thomas Sandefur (Michael Gambon) while a company lawyer tries to force him to sign an expanded NDA, threatening to cut off his benefits and severance. Mann shoots much of the scene in wide, off-balance compositions, with Wigand’s face in extreme close-up on one side of the frame, and the lawyer in full-shot on the other. Such jarring images enhance the noirish peril of the scene, while also evoking Wigand’s growing paranoia. Another sequence, in which Wigand’s security people rush him through an airport to prevent anyone from approaching him, unfolds like something from a gangster thriller; when one man chummily walks up to Wigand and suddenly tosses an envelope at him — serving him with a subpoena — it feels like we’re watching an assassination.

To match the frenetic visual style, Mann populated his cast with actors unafraid of delivering big, broad performances. When we first see Plummer’s Mike Wallace, he’s screaming at a group of gun-toting Hezbollah lackeys ahead of an interview with the group’s leader, all in an effort to get his heart rate up. (Plummer is so good that whenever someone now mentions Mike Wallace, I can only think of Christopher Plummer.) Crowe — who was only in his mid-30s at the time, and would in just a few months show up ripped and glistening in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator — plays the heavy-set, 50-something Wigand as a man consumed with simmering rage, which makes both his firing and his eventual whistle-blowing understandable.

And Pacino is … well, he’s Pacino. He’s probably the American actor most adept at grandiose arias of scenery-chewing emotion. (“I see myself kind of like a tenor,” he told me when I interviewed him last year. “And a tenor needs to hit those high notes once in a while.”) Pacino is actually relatively reserved for most of The Insider. He spends the first half ever-watchful, the very model of a journalist on the hunt for a story. But when CBS executives start discussing possibly not airing the Wigand interview — in other words, when Bergman starts to become the story — the performance gathers fury. And yet, Pacino’s acting never feels outsized; it matches the sudden heartbreak of what we’re watching. The wide-eyed double-take that Bergman does when Wallace reveals that he’s siding with their corporate overlords would seem nutty in most other films. Here, it expresses a genuine moral calamity.

But perhaps The Insider’s most resounding highlight belongs to one of its supporting actors. During a deposition of Wigand in a Mississippi courtroom, Bruce McGill, as the real-life lawyer Ron Motley, tells off a tobacco lawyer trying to force Wigand not to speak. “You don’t get to instruct anything around here,” he bellows at his opponent, building to a crescendo of rage. “This is not North Carolina, not South Carolina, nor Kentucky. This is the sovereign state of Mississippi’s proceeding. Wipe that smirk off your face!” It’s a deliciously cathartic moment. (Mann tells me that McGill actually ruptured an intestine delivering those lines. “He didn’t realize it until the next day!”)

I distinctly recall the audience 20 years ago bursting into applause when McGill’s Motley delivered his speech. It felt like the film was nearing its finale, even though we were really just at the halfway point. That speaks to the tricky structure of The Insider, which requires the story to switch from being about Wigand’s damning revelations to being about CBS’s suppression of Bergman’s 60 Minutes segment. Mann and Roth lay the groundwork for that seemingly sudden shift by always showing Bergman in the context of his day-to-day activities — so that we always see him at work on other stories, be it the aforementioned Hezbollah interview, the manhunt for the Unabomber, or a random New York street shooting. Journalism is a through line from the very beginning — and then it becomes the main subject.

Maybe that’s why The Insider still feels not only relevant, but downright prophetic. Mann’s film captures a key moment in the decline of American journalism, a point when corporate values took precedence over revelations that were clearly in the public interest. But that phenomenon didn’t start with the Wigand case. “There’s a certain level of self-censorship and legal censorship that’s been going on for a long time, particularly on the broadcast side, because it’s an entertainment model,” Bergman says. (He also notes that the Wigand case wasn’t even the first time that CBS pulled one of his 60 Minutes segments off the air for fear of lawsuits from powerful interests.)

It’s also quite striking to see (and to remember) the power and widespread popularity that 60 Minutes once had. In that sense, The Insider feels, for all its foresight, like a curious time capsule, from a period when a TV or newspaper report could actually reach a massive audience and change things. So much so that it was even something of a movie cliché: Once upon a time, you could end a spy thriller like Three Days of the Condor with the hero sending off a package to the New York Times, and know that the truth would finally be heard — that the righteous would presumably prevail over crookedness and duplicity. Of course, that was itself something of a fantasy, but there was a kernel of truth to it. “Journalism enjoyed a period [of popularity] in the wake of Watergate,” says Bergman (who until recently taught journalism at the University of California-Berkeley), “when there was a lot of public education about the value of good information. That’s when investigative reporting became, if you will, fashionable.” Today, it’s hard to imagine that kind of change happening as the result of a news report, even though Bergman says that “there’s more great investigative reporting being done right now than at any time in my career.”

That’s perhaps the final tragic shift that The Insider captures — the point at which power, prestige, and profit became more important than the truth, even to many of those who had ostensibly dedicated their lives to the truth. “You’ve got a disregard for truth regardless of how high the standard,” says Mann, citing the efforts of Fox News and Roger Ailes and others to corrupt information as a way of harvesting resentment in the population. “Today, there’s no revelation one could imagine,” he says, “that would have the power to change outcomes, or at least for more than about two weeks.”

Or, as Pacino’s Bergman says to Plummer’s Wallace in The Insider: “What got broken here doesn’t go back together.”