This review originally ran during the Toronto International Film Festival earlier this year. We are republishing it as the film hits theaters this weekend.

In Ford v Ferrari, the director James Mangold doesn’t hover over the race cars that rocket along at 210, 220, 230 miles per hour and scorch around curves. Overhead shots wouldn’t suit his objective, which is to put you inside or right alongside the vehicles, so that you can’t — for a nanosecond — forget the drivers’ chances of becoming a smoking mash of tin and innards on the blacktop. There’s no defense against Mangold’s hyperkinetic style, but, fortunately, there doesn’t need to be. He doesn’t misuse his head-rattling techniques. He’s an honorable head-rattler. The movie is an old-fashioned rouser with a lot of new-fashioned virtuosity.

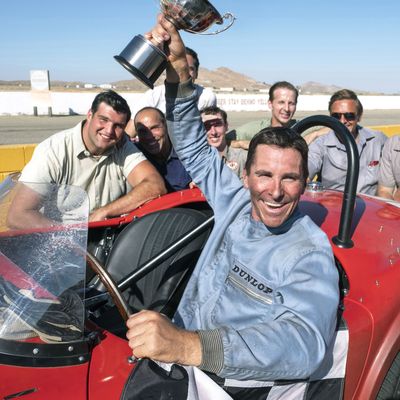

Based on a weirdly true story set in the 1960s, the movie centers on two charismatic purists, the legendary ex-racer Carroll Shelby (Matt Damon) and the rowdy, insolent Brit Ken Miles (Christian Bale), who’s a prodigy both behind the wheel and under the hood. It takes nearly half an hour to get the plot in fifth gear. After being rebuffed and insulted following a failed attempt to purchase the Italian company Ferrari to add hipster cred to his family-car image, Henry Ford II (Tracy Letts) vows to build his own race cars and crush the smug Enzo Ferrari (Remo Girone) in the 24-hour endurance race at Le Mans. Ford exec Lee Iacocca (Jon Bernthal) reaches out to Shelby, who reaches out to Miles, whose penchant for insulting his wealthy but insufficiently auto-sensitive sports car customers has brought him to the brink of bankruptcy. With a blank check, the pair get busy hammering frames and shedding scores of pounds of engine parts.

It’s the most seductive of premises for an American audience: casting us Yanks as the underdog despite having more (ill-gotten) wealth than anyone in the world. One of the film’s cannier touches is creating a wide gap between the capitalist ogre and our working-class heroes, so as to make it plain they’re competing for their sacred selves and not their country and its arrogant, undeserving scions. Letts’s Ford is a big, capricious, over-entitled baby not unlike the one in the White House. (Taken together with his recent triumph as a symbol of rapacious capitalism in the Broadway revival of Arthur Miller’s All My Sons, Letts is cornering the market on venal American patriarchs, while in his other life, as a playwright, crafting bloody satires of American family values.)

Mangold’s other brilliant touch is to make the heroes far more than daredevil grunts. Shelby, Miles, and Ray McKinnon’s Phil Remington are as versed in physics as any Star Trek android. They know the higher mathematics of torque, the long-range torsion of metal. Every third line — including the ones that are traded between Miles and his devoted son, Peter (Noah Jupe), who strives to learn the physics to protect his dad from harm — sounds like a variation of, “If you take out the tech tech tech, you’ll lose the tech tech in the tech.” “But we can compensate with the tech tech.” “Only if we vector the tech tech tech.” “Well, yeah, obviously.” Worked for me. Taking his cues from Sergio Leone, Mangold photographs his stars as monuments as well as men, pitching his close-ups (from below or at slightly canted angles) into the realm of myth without getting ostentatious about it. These are great American archetypes — extra great given that Clint Eastwood had no evident trig. After Damon in The Martian, all American heroes must “work the problem.”

Damon has lowered his pitch and sounds as swaggeringly Texan as George W. Bush attempted to, in vain. It’s hard to connect that baritone to Damon’s still-youthful face, but he’s a witty enough actor to bridge the credibility gap. The dryly macho quips in the script by Jez Butterworth, John-Henry Butterworth, and Jason Keller all land, the dialogue as honed as the racecars, for maximum torque. Damon and Bale go at each other as only marquee titans can, each without fear of being fired for upstaging the star. Bale brings something physical to his driving (pun intended!) delivery: His cheekbones look cut, as if to give Miles an aerodynamic advantage. Bale’s Miles inhabits a different plane than his capitalist masters.

One of those masters is Ford v Ferrari’s true villain, who is not Ferrari but Ford bootlicker Leo Beebe, played by Josh Lucas. Beebe takes a strong dislike to Bale’s Ken Miles and spends the rest of the film trying either to deep-six him or field another Ford Motors racing team that will cast him into second or third place. For more than half the film the rivalry between the smarmy suit and Cockney maverick works like gangbusters, but as we get closer to Le Mans I began to flash back on David Tomlinson throwing monkey wrenches into the life of Dean Jones and Herbie the lovably sentient Volkswagen in The Love Bug. Every time Miles gets close to winning the acclaim he so richly deserves, there’s Beebe to throw up another speed bump, to the point where you have to laugh. That said, I love The Love Bug. Also, Hollywood filmmakers know as well as anyone that the enemy is far more often on their own team than in a rival camp. Lucas plays the guy who’s every conscientious filmmaker’s nightmare.

Though a mite long, Ford v Ferrari is so thrillingly well made that it’s only later, when your pulse slows, that you see how formulaic it is. But formulas are made to be overhauled, and this film has some fascinating upgrades. For example, the old Westerns had prim wives who stood at the doors of their homesteads and said to their upright husbands, “Be careful.” In 2019, Ken Miles’s wife, Mollie (Caitriona Balfe, of Outlander), forces him to listen to her “be careful” by driving the family sedan at 80 miles per hour on one-lane roads while he covers his eyes and shrieks, “Stop! I hear you! I’ll be careful!” The scene doesn’t make a lot of psychological sense, but it certainly signals that Mollie isn’t an old-fashioned pillar of feminine stability, that she has a distinct point of view. The next step toward gender equality would be to give the wife something to do that isn’t borderline psychotic.

*A version of this article appears in the November 11, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!