To commemorate the forthcoming release of Cats, we present the uncharacteristically positive, pun-filled review from John Simon that New York Magazine ran after the premiere of the Broadway production, in the issue of October 18, 1982.

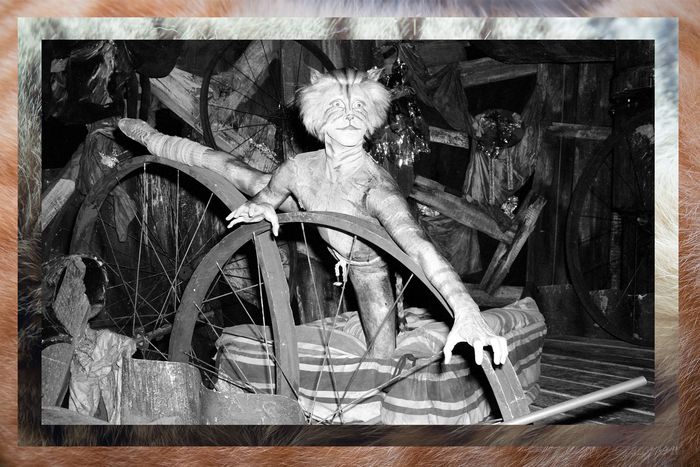

If you like lavishness, if you like opulence, if you like kitty-literature at its grandest, Cats is surely your thing. The moment you enter the Winter Garden, you are transported into a world of junk sculpture by the cubic yard under a dome of many-colored stars that glitter on and off, viridescent cat’s eyes emblazoned on the dark, a Spielbergian flying saucer of colored lights rising slowly above the stage, a semi-abstract townscape backdrop featuring a huge (and soon to be revealed as Jellicle) moon, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s brashly sassy overture pouring at you from an invisible orchestra, and from every part of the theater (high and low) cats, cats, cats scampering, scurrying, scrabbling, and slithering across the auditorium and onto the stage (though there is scarcely a difference between those two areas, the whole world being a catwalk).

Somewhere between $5 million and $7 million (we hear) has been spent on creating this ambience that can vie with the Place de la Bastille on July 14 and the carnival in Rio, and, presto magico, the fur is flying. As you know, the words are from the verse of T.S. Eliot, with some additions by two lesser poets, Trevor Nunn, the show’s director, and Richard Stilgoe. As you also know, these are mostly Eliot’s Practical Cats poems, slight but endearing, plus a few similarly whimsical pieces from the Nachlass, and the already famous “Memory,” concocted from various early poems with some questionable additives. But Nunn, Lloyd Webber, and the rest have molded this material into a semblance of a plot full of Christian esc(h)atology as it might have been preached in the catacombs.

The show has apparently gained in grandeur since its London version, but it has lost one thing: the English accents. That old Tom from St. Louis always strove to out-British the British, and these verses fitted themselves to the British scene and the British tongue. They are somehow less funny with genuine American or fake British accents, though, with one or two exceptions, the New York cast, even when dancing up a cataclysm, manage to enunciate Old Possum’s verses with exemplary elocution, and Lloyd Webber and David Cullen have toned down the orchestrations so as not to drown out the words.

And what of the tunes? In his usual fashion, Lloyd Webber has contrived melodies that vary from the catchy to the merely serviceable, from the vaguely Puccinian to the less categorizably derivative, but very much — including even the mercilessly milked hit, “Memory” — purrloined. Never have I had such a yen to hire a private tune detective to track down the provenance of these songs, but mongrels though they be, they manage to work as a score. They blend in with John Napier’s splendid scenery and costumes, Gillian Lynne’s unspectacular but adequate choreography (particularly as executed by some lightsome, high-flying dancers), David Hersey’s endlessly imaginative and show-stopping lighting, and Trevor Nunn’s canny and effervescent direction into a delightful albeit trivial Gesantalmostkunstwerk.

You will enjoy scenic effects to elate you, stage (and auditorium) movement to keep your eyeballs rolling every which way, talented players galore to thrill you (only one obnoxious performance, by Wendy Edmead), and sundry cunning devices to keep you eagerly expectant, with your expectations almost always astonishingly gratified. But there is, finally, too much dazzlement. As (in a chorus from “The Rock”) Eliot himself said: “In our rhythm of earthly life we tire of the light.” Too much insubstantial smart-aleckiness, too much costly gimcrackery, too many sequined inventions and spangled conceits, and all those orgasms of light all around us — for the first time in my life I found myself agreeing with Jerzy Grotowski’s notion of a “poor theater.” As on certain jukeboxes of yore you could buy three minutes of silence, I yearned to purchase a square foot of ungimmicked-up austerity.

Cats, Sheridan Morley has written, “is about the possibilities of theater,” and with such a caressingly, insinuatingly, ferally feline cast, the pussybilities, at any rate, are limitless. I must single out as my particular favorites Donna King, Harry Groener, Bonnie Simmons, and Stephen Hanan, though there are at least half a dozen others who are scarcely behind them. Betty Buckley, as the aging beauty Grizabella, keeps the pathos within bounds and sings “Memory” (damn it, where was that tune lifted from, anyway?) with commendably understated wistfulness. And Ken Page, as Old Deuteronomy (the song about him is the best in the score), manages to be as massive as Blake’s God and is nicely balanced by Timothy Scott’s winsomely whirling devil of a Mr. Mistoffelees (consistently misspelled in the program).

There is something for everyone — even dog lovers — in Cats: a kind of whiskered Disneyland full of sound and furry. You may justly feel that it is slight and overblown, that it is wasteful (the money spent on it could have kept all the starving cats of China in heavy cream for a century or two) and terribly arch, but you cannot help experiencing surges of childish jubilance, as cleverness after sleek cleverness rubs against your shins.

More From This Series

- Cat Performances, Ranked

- Watch Cats With Us on Instagram Tonight … Please

- Cats Flopped and Then Things Got Interesting