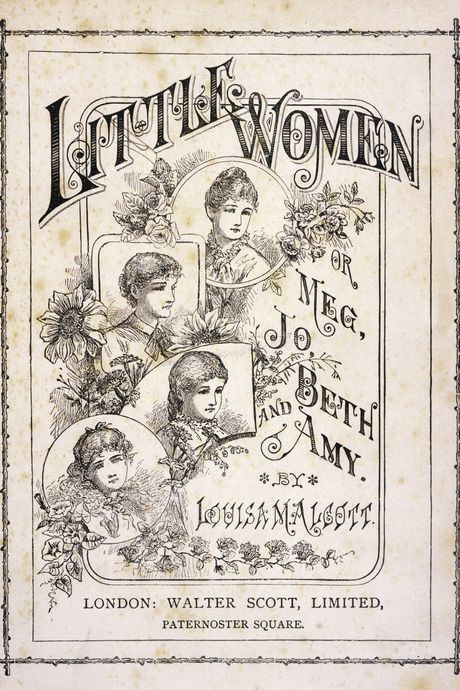

Louisa May Alcott’s beloved novel about the March sisters — Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy, none of whom has a superpower besides Yankee decency — was the original super-franchise.

Spring 1868: She Needed the Money

Louisa May Alcott, who grew up in Massachusetts in a family of abolitionists and was taught by Henry David Thoreau, had been writing saucy fiction under a pen name (stories like “Pauline’s Passion and Punishment”) when her publisher suggested she write a book about girls. Her first thought? “Never liked girls nor knew many, except my sisters.” So she based her book on them (she was Jo).

Fall 1868: Blockbuster

The first part of Little Women (up until Mr. March returns home from the Civil War) is published and sells out its initial run of 2,000 books in two weeks. The book toes the line between children’s and “serious” literature, and is reviewed by Harper’s and The Nation. She quickly sets to work on a follow-up. (They were eventually combined into one book.)

Spring 1869: Book Two

As part two comes out, part-one sales reach such a fever pitch that when Alcott goes to visit her publisher, she thinks his staff is packing to shutter the office. Turns out the boxes are stuffed with copies of Little Women. Alcott’s publisher had told her to name any amount and he’d cut her a check: She returns home with a thousand bucks.

1870: Paparazzi Problems

Alcott’s Orchard House in Concord, Massachusetts, becomes a pilgrimage site for devoted readers. Desperate for a glimpse of the almost-40-year-old novelist, newspapers send sketch artists to sit on her fence and try to capture her likeness. Alcott says she’s considered turning a garden hose on them.

1871: The Franchise

What’s next? How about a sequel: Little Men. After her sister Anna’s husband dies suddenly, Alcott, who never married herself, helps provide for the fatherless family, buying them Thoreau’s house, where he wrote much of Walden. That house sold in October 2019 for $2.46 million.

1880: Stocking Stuffer

Little Women is combined into one volume when Alcott’s publisher, Roberts Brothers, decides to cash in on the holiday season and release a gilded-edge edition suitable for gifting.

1886: Going Meta

Alcott winds down the March saga with Jo’s Boys and turns Jo into a novelist who has written “a little story describing a few scenes and adventures in the lives of herself and her sisters.”

1888: Hospital Sketches

Alcott dies of a stroke at 55. She’d been in poor health for years, possibly as a result of the mercury she’d been prescribed to treat the typhoid fever she caught nursing Civil War soldiers in a Washington, D.C., hospital.

1905: Cosplay for Readers

The novelist Marion Ames Taggart writes The Little Women Club, a novel about … four young girls who attempt to become the March sisters by reenacting their lives. IRL, Little Women Clubs pop up at the same time.

1912: Stage …

The first Broadway production of Little Women is a massive hit. That same year, Orchard House is turned into a museum.

1913: Presidential Fanboy

In his post-presidential Autobiography, Theodore Roosevelt admits that, at the risk of being “deemed effeminate,” he “greatly liked … girls’ stories” and “worshiped” Little Women as a young boy.

1917 and 1918: … And Screen

The first two film versions of Little Women, both silent, are released. Neither has survived.

1927: The New New Testament

American high-schoolers are polled on “What book has influenced you most?” Little Women takes the No. 1 spot. The Bible has to settle for second place.

1933: “Christopher Columbus!”

RKO releases George Cukor’s celebrated film starring Katharine Hepburn as a galumphing tomboy version of Jo. It’s a hit and wins the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar. Louise Closser Hale, who is cast as Aunt March, dies during filming, and a new actress is brought in to reshoot her scenes. The National Council of Teachers of English hands out study guides to every American high school.

1933: Merch

Madame Alexander begins producing a line of Little Women dolls. It still does: Jo will run you about $130 at Neiman Marcus.

1949: Not in Kansas Anymore

Film studios have another go, this time with June Allyson as Jo, Elizabeth Taylor as Amy, Margaret O’Brien as Beth, and relative newcomer Janet Leigh as Meg. O’Brien carries a basket around for much of the film — the same basket Judy Garland toted as Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. The film grosses nearly $3.5 million in the U.S.

1950: Not Jo’s Boys

When Orchard House is vandalized, with nearly 100 windowpanes broken, police point to the obvious culprit: “Small boys.”

1958: Sing It, Jo!

Broadway composer Richard Adler, best known for The Pajama Game, makes a musical Little Women to air on CBS.

1973: But Is It Feminist?

A New York Times article, “Does Little Women Belittle Women?,” argues that it does. Critics (including me) haven’t stopped arguing about it since.

1977: Yes! It Was for Its Time!

Some members of the feminist movement take up Jo as one of their own; academic Carolyn Heilbrun writes that “Jo was a miracle” and a role model for “girls dreaming beyond the confines of a constricted family destiny.”

1978: Professor Kirk?

In an NBC miniseries version, Susan Dey (Laurie from The Partridge Family) plays Jo. Her Professor Bhaer? William Shatner.

1970s-80s: The Touchstone

Even though Little Women is dropping off reading lists and is rarely talked about in schools, countless novelists and essayists embrace it as formative in their literary education. Cynthia Ozick: “I read Little Women a thousand times. Ten thousand. I am no longer incognito, not even myself. I am Jo in her ‘vortex’; not Jo exactly but some Jo-of-the-future. I am under an enchantment: Who I truly am must be deferred, waited for, and waited for.” Ursula K. LeGuin: “From the immediacy, the authority, with which Frank Merrill’s familiar illustrations of Little Women came to my mind as soon as I asked myself what a woman writing looks like, I know that Jo March must have had real influence upon me when I was a young scribbler.” Erica Jong: Little Women “told me women could be writers, intellects — and still have rich personal lives.”

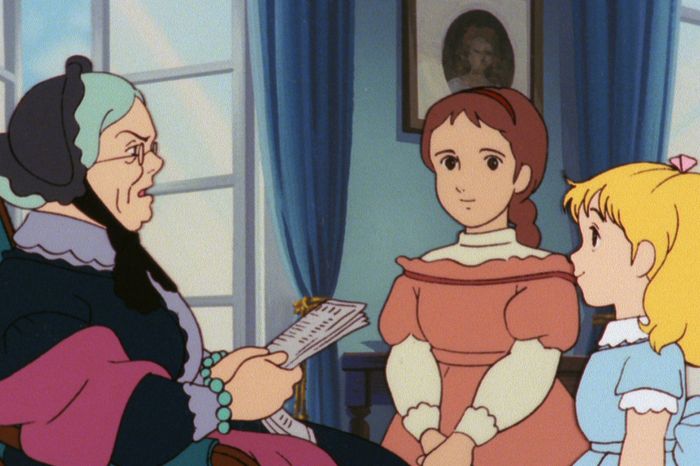

1987: Big in Japan

A 48-episode anime version, Tales of Little Women, or “Love’s Tale of Young Grass,” takes some liberties with the story, putting the March family near Gettysburg during the Civil War. (Their house is destroyed during a battle.) The book reaches astounding heights of popularity and is cited in a 1999 article as Japan’s second-most-beloved children’s book (after Anne of Green Gables).

1994: Winona’s Turn

After 12 years of shopping the script, writer Robin Swicord and executive producer Amy Pascal complete a new major film version of the book. The pair bring in a female director — Gillian Armstrong — and a cast led by Susan Sarandon and Winona Ryder. As Armstrong told the New York Times, “Fifteen men in suits watched [the rough cut], and one of the most moving, memorable moments of my life was when the lights came up and they said, ‘We were dreading having to come and see this little girls’ film, but we loved it and we cried. We want to give you some more money.’” The new film kicks off another round of debate among writers who can’t decide whether Alcott embraces patriarchal convention or flips it on its head.

1998: Le Donne Piccole

Composer Mark Adamo’s Little Women opera premieres in Houston.

2005: Fan-Fiction

Geraldine Brooks publishes March, about Mr. March’s trials returning north at the end of the Civil War.

2017: Antacids, She Wrote

The BBC debuts a new TV version — the Beeb’s fourth — with Angela Lansbury as a British-inflected Aunt March who complains about indigestion.

2018: 150 Years

The book is reconsidered on the occasion of its 150th anniversary. Anne Boyd Rioux’s Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters kicks off a barrage of essays on its enduring appeal despite slipping off school reading lists.

2019: It’ll Still Make You Cry

Greta Gerwig releases her own version of the classic, which grapples with “all of these inappropriate emotions for young women to have.”

*This article appears in the December 9, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!