Spoilers ahead for the most recent episode of Mr. Robot.

This week’s episode of Mr. Robot featured the end of Philip Price, the power-hungry CEO of E Corp with ties to cyberterrorist Whiterose and the Dark Army. Though he was one of the series’s primary villains, Price eventually outlasted his usefulness to Whiterose, which led to his professional ruin but also an honest reconciliation with his estranged daughter, Angela Moss (Portia Doubleday). He coaxed her out of a brainwashed state that led her to do the Dark Army’s bidding and tried to convince her to put the pieces of her life back together. But when Angela vowed revenge, Whiterose unceremoniously killed her, leading Price to seek his own revenge by allying with Elliot and Mr. Robot to take down the Dark Army once and for all.

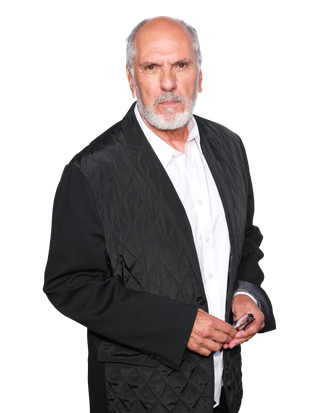

Michael Cristofer, a Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright, director, and longtime actor of stage and screen, has played the character of Philip Price for the past four seasons; his gruff but warm demeanor is a consistently welcome presence on a series that has gone through many tonal shifts, stylistic experiments, and character changes. Vulture caught up with Cristofer to discuss his final episode on Mr. Robot, death scenes, monologue advice, and his work on the cult series Rubicon.

When you first appeared on the show, Philip Price had a much more malevolent energy, but by the end, he had shifted allegiances and had been significantly chastened by intervening events. How do you view Price’s full arc?

I think when [Mr. Robot] started, it picked Price up at a moment in his life when he pretty much accomplished everything he had wanted to accomplish. He was in a position that set his ego and sense of self-worth, which was pretty high. He had achieved a kind of success that put him in a position close to God. He had a real feeling of superiority to the world, and a kind of detachment from the world. He was sort of watching the world from a distance as if he was viewing mice in a labyrinth or cockroaches running around. Just fascinated by what human beings did, but never really being connected to humanity in any way. At least we didn’t see that. That’s who he was.

And then the character of Angela walked into his life. Although we didn’t know it at the beginning, it was his daughter, but I do think that character opened a crack in Philip Price. He became more and more attached and fascinated by Angela as a way of getting back the things he turned his back on: a kind of intimacy, a kind of simple friendship, maybe a kind of love. All the things that he had denied himself in an effort to achieve ultimate power. He became what he never was before, which was vulnerable. That was the beginning of the end, or depending on how you see it, the beginning of his becoming a better human being.

Do you view Price’s change of heart as a moral realignment or a fundamentally mercenary decision? Did he just want to stick a fork in Zhang’s eye as revenge?

I think it was a change of heart. I think there was a great joy in the face of death, because I think he knew at that point he wasn’t getting out of there alive. [Laughs.] There was a great joy in the fact that he had found something that could defeat Zhang, and although that might be the mercenary part of it, that thing was the extraordinary affection that the people had for Angela. He understood that was something better and bigger than he was. I like to think he came to a real, new moral position in the face of everything that was happening.

When did you learn your character was going to die?

I guess that was the beginning of the season. You know, these guys [like Philip Price] are like cockroaches. You just think, no matter what happens to the world, they are going to survive somehow. I always said about Price that every disaster was an opportunity for him, so no matter what happened, you always think, Well, these guys survive. But at the same moment that I realized he was dying, I also got the script where Angela was murdered, so then I understood he was no longer the invincible cockroach, that he achieved vulnerability, and that was going to be the end of him.

As someone who’s acted onstage and screen for a long time, do you approach death scenes in a certain way? I feel like that’s a specific type of acting that requires a certain set of skills.

Half of it is technical, depending on how you are killed. Dying a slow death in a bed from some terminal disease is very different from being shot dead on the steps of the Bronx County Courthouse. This was a bit technical because of the huge camera crane things [Sam Esmail] was doing and because of the weather. We were in the rain and it was cold. You have to find out what it’s like being shot; I was shot in the back and turned then I was shot in the front. Then there’s that magic thing of what is a person expressing in that moment. I guess this was more spontaneous because it happened so fast; there wasn’t really the time to act. We did a couple of takes where I did almost laugh, but Sam didn’t use those, probably wisely. Price was basically almost drunk, and he kind of knew it was happening, and in a funny way, it was in line with his character that he was almost distanced from what was happening to him. This was a guy who was looking down on what’s happening even though it’s happening to him.

Has your process changed over the years? Do you prepare or rehearse differently now than when you did, say, in the ’70s when you were onstage?

Yes. I started as an actor and then I moved over into playwriting, and then playwriting led to screenwriting, and then screenwriting led to some directing, but in that long process, there was about a 10- to 12-year period where I didn’t do any acting. There wasn’t any time. I was really working hard as a screenwriter and then as a director. When I went back to it, I realized that the first 10 to 20 years of acting, it’s all about you. No matter how small your part is in the movie, the movie is about you. No matter how small your part is in the play, the play is about you. Everything that has to happen has to happen for you. Having gone to the other side of the table, so to speak, suddenly when I went back to acting, I knew what the job was and I knew what my place was. There was a great sense of freedom that came with that. When you have five lines in a movie and you think the movie depends on you, you’re really taking on a lot more pressure than you need to.

Creativity is spontaneous and spontaneity only happens when you are free, when you are loose, when you are not stressed or under pressure, and being on the other side of the table made it very clear to me what my job was. It just created a much better atmosphere. I created a much better atmosphere for myself. I felt much freer as an actor when I went back to it than what I had been before. With that period of not doing it, I think that was really important.

You first came to my attention when you starred on Rubicon …

Aah, Truxton! Truxton Spangler!

I always viewed Price as an alternate-universe Spangler. I wonder if you viewed these characters on a continuum in any way.

I think the reason Sam asked me to do Price was because of Truxton. I think that’s true. I do see the connection, obviously, but then there were differences too. Rubicon was basically written by Henry Bromell, who was an extraordinary writer and a wonderful guy, and he passed away very young. He went on to create Homeland and then he died of a heart attack completely unexpectedly. Henry’s father had worked with the CIA, and Henry also worked at The New Yorker magazine, and one of the editors at The New Yorker had these idiosyncratic behaviors. Truxton always did peculiar things. Wiping his mouth with his tie when he was eating cereal all the time. Henry really loved all that stuff, so I explored that as much as I could in terms of that character. That was great fun. It was a shame that show just didn’t go anywhere. It was really good.

As someone who has delivered many monologues — I’m especially thinking of the “tie speech” from Rubicon or your lengthy rebuke to Zhang in your final scene — do you have any advice on preparing for a monologue?

When you suddenly look at a script and there’s a page and a half of talking, the important thing is that it doesn’t sound like you’re talking for a page and a half. That’s the trick, really. I’m not the first one to say this — I think it was Kazan, actually, who said it — but the best thing about an actor is when you don’t know what he’s going to do next, and I think that’s especially important when you have a long speech. You have to approach it so specifically, moment by moment, that it could end or go on. So often I think actors say, “Oh, here’s the beginning, here’s the middle, and here’s the end, and I’ll make it all really beautiful,” but the point is it has to feel like you might stop talking at any moment. Then a new thought comes to kick your ass into the next sentence. That’s how you keep it alive.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.