Jonathan Pryce was shooting a scene for the FX pilot Going Hollywood when he found himself completely unraveling. He couldn’t remember his lines, or handle any of the props. He was a wreck: nervous, vulnerable, angry with himself. The reason for this utter disaster? Someone had given him the worst thing in the world: a compliment. Pryce was playing the head of William Morris, and as he was arriving for his first day of filming, the show’s dialect coach happened to mention that series lead Nikolaj Coster-Waldau had called the 72-year-old stage veteran one of the greatest actors he’d ever worked with. The encounter left Pryce with a fatal bout of self-consciousness. “I thought people were looking at me not as the character but like, You’re so fucking good,” he recalled later. “And it was all from this guy saying, ‘People think you’re wonderful.’” His theory of his own performance rests on the element of surprise: “If I sneak up on people, then I’m happy. If I’m comfortable, I can’t do it.”

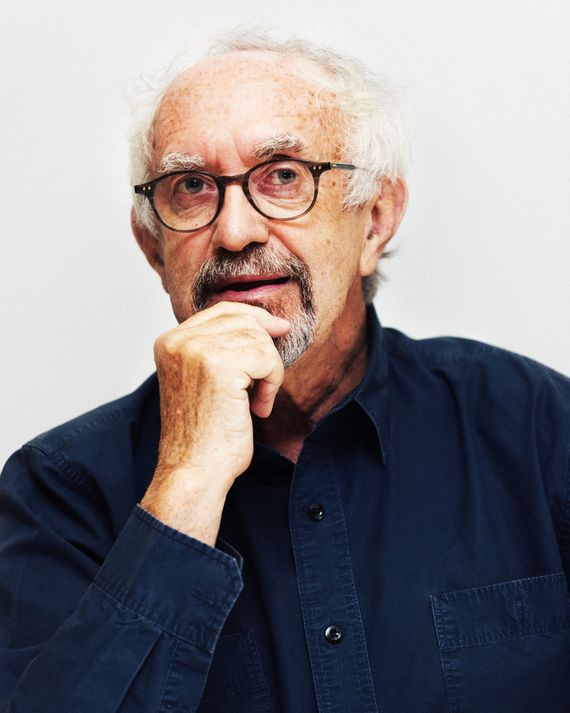

Over his five decades in the profession, Pryce has toed the line between movie star and character actor. He is often cast in parts that invest him with a high degree of personal authority: religious leaders, colonial officials, prize-winning novelists. It is perhaps a sign of how we are feeling about such authority these days that recent roles have required him to die over and over again, sometimes in curiously similar ways. On the TV series Taboo, he had a moment of anxiety upon learning that his character was to perish in an explosion; he was forbidden from revealing that he had just been blown up on Game of Thrones, too. “I see it as a kind of good luck, a little talisman,” he says, chuckling. “I keep dying in fiction, so in life I’m okay.”

It is not a spoiler to say that Pryce survives his latest project. In Fernando Meirelles’s The Two Popes, he plays the second pope: Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, the future Francis, a liberal reformer who spends a pivotal few days with his predecessor, the archconservative Pope Benedict XVI (Anthony Hopkins). Like Pryce, the film sneaks up on you. There’s a certain does-what-it-says-on-the-tin charm to it: The Two Popes does indeed feature two popes, and often only the two popes, as the papal odd couple bickers, debates scripture, and eventually strikes up an unlikely bond. It’s the kind of movie you relax into, like a comfortable chair. Since its Telluride premiere, the film has established a reputation as a crowd-pleaser, winning audience awards at festivals in Miami, the Hamptons, and Virginia, and leading the field in this year’s AARP Movies for Grownups nominations. It’s currently enjoying a brief theatrical run before heading to Netflix on December 20. Considering the Academy’s penchant for inspiring stories about real-life figures, The Two Popes could end the season as the streamer’s dark-horse Best Picture contender.

So, once his Broadway run in Florian Zeller’s The Height of the Storm wraps up shortly after our conversation, Pryce will hit the campaign trail in support of the film. (If he manages an Oscar nomination, it will be the first of his long career.) Glad-handing may not have come naturally to Pryce in the past, but his higher profile post-Thrones has made him a bit more open, more relaxed about interacting with fans. Like Bergoglio, he takes pride in getting out into the world. Unlike the Pope, he considers himself to have precisely the right level of fame. The morning of our interview he was sitting in a coffee shop when a man approached him and told him he was excellent: “The people next to me were like, ‘At what? What is he excellent at?’”

Around this point in our conversation, a pair of strangers attempt to enter the hotel conference room the actor has booked for the interview. We shoo them out. “So much for my nice openness to other people,” says Pryce, who enjoys affecting a mock-theatrical self-importance. “Get the fuck out of here, can’t you see I’m talking about myself?”

The real Francis’s ascension came around the same time Pryce was playing the High Sparrow on Game of Thrones, and many people, including him, remarked on the similarities between the two. In Thrones’ fifth season, the character was introduced as a humble shepherd who offered care and comfort for the smallfolk of Westeros. This was the only side of the character Pryce was aware of before signing on. “Of course, I hadn’t seen the twist coming,” he laughs. The following season, the High Sparrow revealed himself to be “a monster — homophobic, cruel, despotic. If it had started with season six, I might not have done the role.” There’s a parallel here to Brexit: In Pryce’s account of the “bloody nightmare,” the 2016 referendum was a protest vote against austerity by the nation’s dispossessed, which has now resulted in the rise of the hated Boris Johnson, “a leader who is palpably an idiot.” When it comes to the fruit of populist rage, we don’t exactly get to pick.

Pryce, a lifelong socialist, has large, expressive eyes, and while his most famous roles see them go coldly sardonic, playing the Cool Pope has given him good practice at filling them with warmth. While doing research for the role, though, Pryce spoke to a Jesuit priest who’d worked under Bergoglio, who suggested that the happy, outgoing figure often seen in the media was born the day he became Francis. “I asked, ‘Did you like him?’ He said no,” Pryce recalled. “He said he was very strict and authoritarian. When he was made pope, they saw him on the television, and they didn’t recognize him because he was smiling. They knew him as the man who never smiled.”

When he’s playing authority figures, Pryce is drawn less to power than to weakness anyway, which is one reason the compliment on the Going Hollywood set distressed him so. In his estimation, Bergoglio’s elevation to the papacy was a chance to wipe his moral slate clean — a fascinating character note. “Obviously, he must have felt redeemed. At last he could be the person he wanted to be. He had the power, if he used it, to do the good that he needed to do.”

The Two Popes arrives in a fraught moment for redemption. Recently the culture has seen a greater focus on accountability, on not letting past wrongs go unaddressed. Most of us can agree that this is a good thing. But it’s had the necessary side effect of pushing forgiveness further down the list of progressive values, as activists question who gets to expect absolution, and for what. Much of the film’s drama centers on the guilt both men are carrying for sins in their pasts. As a cardinal, Benedict allowed a German priest known to be a pedophile to be transferred to another parish, where he continued to molest children. Francis has been accused of various degrees of complicity with the military dictatorship that ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983. (He denies it, but Pryce notes that since his elevation he has not been back.) How do you square the values of accountability and forgiveness? “The short answer is, life is too short not to forgive,” Pryce says. “Forgiveness will cleanse you.” He has felt this lesson harder than most.

Pryce’s father, Isaac, was the kind of guy that everyone in their village knew. He was a grocer and a local councilman, and like Bergoglio in The Two Popes, he had the gift of being able to strike up a rapport with anyone he met. In the mid-’70s, he was working in his shop when he was attacked by a 16-year-old boy, who hit him in the head with a hammer. Initially the assault did not seem fatal, but that night, Isaac had a stroke. He never recovered, and died two years later. In the decades since, Pryce has spoken frequently of unresolved issues relating to his father’s killing. He says that he has been able to let go of any rage toward the person responsible. “I didn’t ever say to myself, I forgive this boy. But I didn’t pursue him, or the anger.” Instead, he channeled his emotions into his work, playing another son struggling to process his father’s death in a landmark production of Hamlet at the Royal Court. In this staging, the role of the Ghost was cut — Pryce’s Hamlet spoke the lines himself, as if possessed by a vengeful spirit.

Still, he has not forgotten the boy. And elsewhere in life he retains a profound memory for betrayal, like the time a beloved kindergarten teacher smacked his knuckles with a ruler for something he’d never done. “I carried that all the way through,” he says. “I would give myself to someone and think, This is going to end badly.” Perhaps that’s why, while he’s incredibly proud of the new movie, he also fears the intense spotlight of the awards race. Recent seasons have seen plenty of contenders suddenly become their year’s official Oscar villain, and The Two Popes, which in its buddy-comedy dynamic and liberal-humanist politics is not entirely dissimilar to Green Book, could be next. “I worry about this film,” Pryce says. “It’s gone so incredibly well at all the screenings that somewhere, somebody is going to write it off, you know? I always think that’s round the corner.”

He’s lived it once before, in another phase of his career. In the late ’80s Pryce was a respected Shakespearean actor, but after finding himself blown away by Les Misérables, he decided to try his hand at the gigantic West End musicals that were then in vogue. His first effort was debuting the role of the louche, mixed-race Engineer in Miss Saigon, a physically dazzling performance, that earned him the Olivier Award. In the early days of the production, it also called for him to wear bronzer and facial prosthetics to appear more convincingly half-Asian. Pryce eventually ditched the yellowface, but when the production transferred to Broadway in 1991, his casting was protested by Actors’ Equity, as well as many Asian-American actors. After a reverse backlash from critics like Frank Rich, and some hardball from producer Cameron Mackintosh, Equity backed down, and Pryce kept the role. He won the Tony too.

This is not a topic Pryce relishes revisiting. One, it was half a lifetime ago, and he would much rather discuss the times he was the one doing the protesting, like when he threatened to drop out of a production of Macbeth after learning it was sponsored by a bank that did business with South Africa’s apartheid regime. Two, with a sensitive subject like this, there’s always the risk that he might say the wrong thing and wind up setting off the very backlash he fears is coming. (The ghost of Charlotte Rampling must haunt every actor on the trail.) And three, the trickiest thing about the whole situation, he says, is that “I was agreeing with them, you know?” For an actor who’d always considered himself a racial progressive, being at the center of the firestorm stung, but on principle, Pryce admits the protesters had “a really valid argument.” There does, though, remain some residual soreness over the ideals of color-blind casting not applying to him, and he takes issue with the notion that he should only handle roles of his own ethnicity. Consider The Two Popes itself, in which a German and an Argentine are played by two blokes from Wales. And then there are the performances Pryce has given as characters named Nat Dayan and Ike Zimmerman: “If I couldn’t play a Jewish person, my career is out the window.”

Maybe this is another example of liberal values coming into conflict: Most of us agree that actors shouldn’t be limited to roles that fit their exact demographic descriptions, but we would all also like to see nonwhite actors get the same chances their counterparts do. Pryce agrees, but before we can dig in further, his publicist appears. We’ve gone over time, there’s room for one more question. In our discussion about forgiveness, he mentioned how the passage of years brings a new perspective. What does he see differently now? “I feel anger, but my physical outbursts of anger have decreased,” Pryce says. “Maybe I haven’t got the energy any more.” Then, with a hearty laugh, that roaring voice returns: “So you can fuck off!”