To celebrate the forthcoming release of Cats, a film adaptation of the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical, we asked Dickinson creator Alena Smith to reflect on what the inscrutable tale of a junkyard filled with cats can teach us about storytelling.

Great stories define us. The better they are, the bigger their audience. The best get handed down from generation to generation and, in the process, they make a lot of money. This is how we know that Andrew Lloyd Webber’s children’s musical Cats, which ran on Broadway for 18 years and made over $3 billion (fact), is one of the greatest stories ever told.

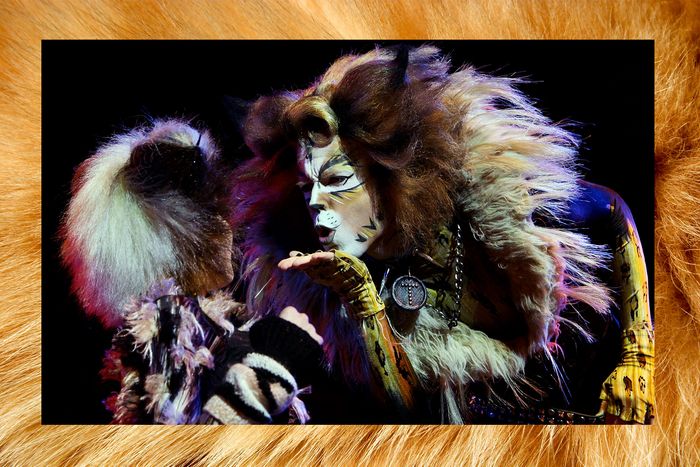

But strangely enough, despite its wild success and firm status as a masterwork, it may seem at first glance that Cats has no plot. It may seem that way at second glance too, even after staring at it and thinking about it for hours. Yet surely, this sung-through feline-based musical, which ran for nearly 9,000 performances in London and is now being made into a star-studded feature film with — get this —digital fur, must be a powerful example of storytelling done right. So let us study Cats and learn its secrets. As Joseph Campbell tells us, the Hero has a Thousand Faces — and, in this case, its face is a cat.

I. Plot

Aristotle conceives of plot as the outline or armature of the story, that which supports and organizes the rest. Plot, he says, is the very thread of design that makes the tapestry of narrative possible. And if Aristotle saw Cats, he would recognize that its plot boils down to this: A group of singing cats gather around a pile of trash, introduce themselves, and then decide which one of them gets to go to space. Simple? Yes — perhaps, deceptively so.

A great part of the secret of dramatic storytelling structure lies in this one word: tension. To engender, suspend, heighten, and resolve a state of tension — that is the goal of the storyteller’s craft. The tension of Cats begins immediately upon entering the theater and viewing the set, which is, as stated, a giant pile of trash. The items in this junk pile are noticeably, even disturbingly, large. There is a massive, crumpled, empty bag of chips, possibly Doritos. There is an enormous, dirty bra. What is all this garbage, and why is it so big? I don’t know about you, but I’m already nervous. The tension has begun.

This stressfulness escalates when, suddenly, from out of nowhere, a whole bunch of borderline-sexy, borderline-revolting spandex-covered cats come prancing out and join together in the moonlight (moonlight equals mystery, which equals plot). Now I’m really scared. Who the hell are these cats, and why do they have human breasts and genitalia?! The master storyteller has me right in his clutches.

From these thrilling first moment, Cats leads us through the archetypal journey that all great stories tell. We hit all the major beats, or “tent poles,” of a classic tale: the part where a horny, well-hung cat introduces himself, the part where a fat old gay cat introduces himself, and of course, the part where the cat who is unofficially in charge of the night train to Glasgow assembles an entire railroad out of discarded bits of garbage. From Inciting Incident (lazy cat just sits and sits) to Crisis (notorious pair of cat thieves steal jewelry) to Obligatory Scene (one cat goes to space, but who?), what a ride we are on … a ride that only perfect storytelling structure could make possible.

II. Character

Now for something that we in the storytelling biz call a “twist.” We have been talking about “plot,” yet what is plot, really, but character? What is an event but a change in a life, an action undertaken, a choice? True character, says the great Robert McKee, is revealed in the choices a human being makes under pressure. Well, in Cats, there are only cats, and there is only one choice to be made. The Jellicle Choice. Made by the Jellicle Cats, at the Jellicle Ball, under the Jellicle Moon. And since this is literally the only thing that happens in the whole show? The pressure. Must. Be. Huge.

Which is why Cats puts off the pivotal “Jellicle Choice” for as long as it can … and in the meantime, delves into its riveting, truly scientific character explorations. Cats shows us the things that cats do, things we always kind of knew that cats did but never really thought about — like stealing jewelry. Cats are always stealing jewelry! Of course! That’s a beautiful detail ripped from the headlines of real life.

So how does a writer create a character? Or really, a tribe of characters, who are all cats with human genitalia? Whether it’s a cynical cat or a rabbinical cat (yes, cats are rabbis), the writer, in his own way, must act the role. So get on your hands and knees, and start prowling around. Lap up some milk. Lick your paws. You’re now a cat who is also a rabbi. Just fucking go for it.

And remember, a story has to happen to someone, because a story is, in fact, a quest. One of the questions asked by Cats is, wouldn’t it be nice if that someone was named Bustopher Jones? To understand his quest, you must ask yourself: Who is Bustopher Jones? What are Bustopher Jones’s intentions? What does Bustopher Jones want?

III. Quest

In order to draw a character out with absolute precision, try an exercise. For the purposes of Cats, you could ask yourself:

Q: How does my character make a living?

A: My character, Skimbleshanks the Railway Cat, makes a living running the night train to Glasgow. This is a normal occupation for a cat and nobody has any questions about it. In fact, the train literally cannot start without Skimbleshanks, which is what gives Skimbleshanks his political power.

Q: What are the stakes for my character, and what’s on the line if (s)he fails?

A: The stakes for my character, Mr. Mistoffelees, the original conjuring cat, are to do magic tricks better than any other cat. If he fails, he will no longer be considered the cleverest of all the cat magicians. Which, obviously, would suck.

Q: If I were my character in these circumstances, what would I do?

A: If I were my character, Old Deuteronomy, and I was the old wise patriarch of the Jellicles, and it was my job to decide which of the cats gets to go to space, I would take the decision really seriously. I would have all the cats introduce themselves, one by one, so I could consider my options. Then, in the end, I would choose Grizabella the Glamour Cat, because she is lonely and ragged and she sings “Memory” and I feel sorry for her. I would then ride with Grizabella, rising up from the junkyard on a dirty old car tire, until a certain point when I’d hop off and let Grizabella go the rest of the way up to space by herself. Then I would call it a night.

Q: Finally, what does my character desire?

A: My character, Grizabella the Glamour Cat, has just ascended to cat heaven and … shit, I don’t know, I think she’s just as confused as the audience is at this point. Which is why the show is over. That’s mastery.

In conclusion, if you dream of success as a writer, you may yearn to create a story as moving and universally beloved as Cats. You may hope to weave a tale so compelling that, like Cats, it will last “now and forever.” Maybe you could even adapt Cats into a TV show! But be warned, success in the storyteller’s craft can be bittersweet. In the words of Jenji Kohan, showrunning is a pie-eating contest where the prize is more pie. And in this case, the prize … is more cats.

More From This Series

- Cat Performances, Ranked

- Watch Cats With Us on Instagram Tonight … Please

- Cats Flopped and Then Things Got Interesting