Charles Fuller’s 1981 A Soldier’s Play, an investigative procedural as crisply executed as a military heel-turn, is premiering uptown at last. What took so long? When it first ran, it was one of the great success stories of the Off Broadway Negro Ensemble Company and a star-making hit for actors like Samuel L. Jackson and Denzel Washington. When Fuller adapted it as a film (and renamed it A Soldier’s Story), he was nominated for an Oscar. The play itself won a Pulitzer. But Kenny Leon’s production for Roundabout Theater Company is only now coming to Broadway.

Plays only stay in the imagination if they’re revived or taught. For years, A Soldier’s Play was caught between two stools: too conventional for the formalists (it has the rhythms of a Law & Order episode), too serious about internalized racism for the feel-good entertainment junkies. It’s also almost fetishistically male. The narrator and hero is a military lawyer, Captain Davenport (Blair Underwood), who wears mirrored sunglasses and generally acts like a bad-ass hard-edge supercop. One-third of available stage time is him slowly standing up from the edge of a desk and snapping a salute. The second act opens with him buttoning a shirt over a shining chest, a kind of worshipful moment for masculine perfection. I don’t know how audiences handled it in 1981, but when I saw it, a woman in front of me groaned out loud. That’s a hard quality to capture in a classroom.

A Soldier’s Play opens with a murder. On a high platform in the back of the stage we see a middle-aged Sergeant Waters (David Alan Grier) stumbling, drunk. “They’ll still hate you!,” he shouts at an unseen figure, laughing strangely. “They still hate you!” Two gunshots. When the lights come back up, it’s 1944 in the Fort Neal, Louisiana, barracks, where a company of black soldiers is being roughly searched for weapons. The sergeant’s body has been found, and, sure that Klan members from the nearby town killed Waters, the military brass is eager to clamp down on hypothetical reprisals. The company’s white Captain Taylor (Jerry O’Connell) doesn’t seem to like confining his men to base, but what he likes even less is the arrival of Davenport, a black officer tasked with the investigation. The play then consists of Davenport’s interrogations — which lead to flashbacks of Waters’s interactions with the other soldiers — and Taylor’s carping at Davenport’s process.

On one level, the play is pleasurable as a murder mystery, which parcels out its information carefully, full of misdirections and red(neck) herrings. That pleasure lingers, though the stories about Waters get more and more terrible — we see his resolve to gain power in the white man’s army, his vitriolic hatred of black Southerners, and his harassment of the sweet-tempered Memphis for being a “ignorant low-class geechy.” As the whodunit fun starts to turn cold and frightening, David Alan Grier’s performance then becomes the show’s main engine. He machines each of his scenes to the inch, developing his portrait from a comic tinpot bellower into villainy and then, remarkably, something more tragic.

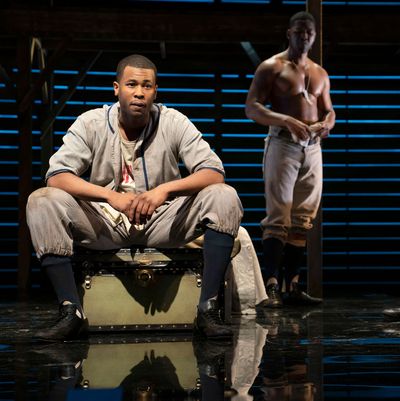

Director Leon loosens the play’s rather careful detective-logic plot by filling transitions with singing — the men frequently strike up a cappella harmonies, beating on their own bodies as percussion. In casting, he has clearly focused on the fact that the company is also a baseball team. (Waters, borrowing the officers’ racism, both hates and prizes the fact that his men can beat white players.) The star players, Private C.J. Memphis (J. Alphonse Nicholson) and Private First Class Melvin Peterson (Nnamdi Asomugha), move like athletes, but there’s also always a logic to how the group moves onstage. There’s a palpable sense of a team at work.

Fuller took two things as his inspiration for A Soldier’s Play: his own time in the army and Melville’s Billy Budd. In that weird, quasi-religious novella, Billy, the “handsome sailor” beloved by his fellow shipmates, attracts the hatred of an officer called Claggart, who frames him for mutiny. Fuller chose to let Billy/Memphis slide almost out of focus (he suffers but is mainly offstage) and look instead at the Claggart figure: His Waters is a man drowning in hatred. If you have the Melville in mind, with its backdrop of British naval abuses, you’ll know to blame the army for Claggart’s damage even before the exposition makes it clear. It also might explain the look of this production. Derek McLane’s huge wooden matrix seems at times like a ship’s dockyard scaffolding extending out of sight.

In 1983, Amiri Baraka took serious exception to A Soldier’s Play and Fuller’s “descent into Pulitzerland.” In an incendiary essay for the Black American Literature Forum, Baraka attacked Fuller’s plot as cowardly and reactionary, particularly given that he believed the Peterson character (originally played by Denzel Washington) was coded as Malcolm X. That figure’s violence in the play and the price he pays for it seemed to Baraka to be a punishment leveled at all black radicals (perhaps even meant to keep white audiences placated), and he hated the way that the play’s sympathies are funneled towards Davenport’s starched, “soldier in the man’s army” correctness. By the time Baraka calls the Negro Ensemble Company a “house slave’s theater,” most readers are backing nervously away from the page. But then Baraka’s rhetoric was often this way — a bazooka at a knife fight.

You can understand a little of what was eating at him, though. Despite its rich inquiries into respectability politics, colorism, black anti-Southern bias, and white terrorism, the play cossets Northern white sensibilities in two respects. First, A Soldier’s Play is safely set far away in the South, where those “real” bigots live. And second, while the narrator is Captain Davenport, and the plum role is Sergeant Waters, the man who changes the most is Captain Taylor. Fuller’s compositional complexity can flatten and turn didactic around this character — perhaps because sentiment is often how writers try to change hearts and minds. That small soft spot remains in this production. For instance, at their farewell encounter Captains Davenport and Taylor finally and meaningfully shake hands. In this, Kenny Leon’s staging echoes a moment in Norman Jewison’s film of the play. (Not for nothing, Jewison’s movie In the Heat of the Night also ends with a handshake between a Northern black investigator and a white racist who has gradually learned to respect him.) There’s a world of absolution and reassurance in that kind of handshake.

Captain Taylor, though, is a pinprick. When he isn’t onstage, we’re in the more complicated Melvillian world of the men in the barracks, in which Memphis bewitches and annoys them with his farm-boy belief in Farmer’s Dust (a container of dirt he swears has lucky powers); where Waters turns military protocol into a weapon; when army life, with the constantly withheld possibility of war, seems to run endlessly and pointlessly around the bases. That, for me, is A Soldier’s Play’s greatest decoration — the very real rhythms of life in uniform, once part of men’s common experience and now largely lost in the modern theater. But when it comes to the production, the medal has to go to David Alan Grier. His performance has size and precision, monstrosity and humanity. Technically, he was playing Waters. But it seemed at times as if he was playing an entire Shakespeare play. Sometimes he was Iago; sometimes he was Othello. And in the moment that he crashed to the floor, both sinned against and sinning, he was somehow a soldier playing both at once.

A Soldier’s Play is at the Roundabout’s American Airlines Theatre through March 15.