On Sunday night, the evening the New York Times unveiled its endorsement in the 2020 presidential run, the editorial boardÔÇÖs Twitter account made an unusually promotional announcement: Before the endorsement was published online and in print, it would first be revealed on The Weekly, the TimesÔÇÖ FX docuseries. Rather than just giving a name and an explanation for the choice, the idea was that The Weekly would provide unprecedented transparency into the selection process. Viewers could watch members of the editorial board grill candidates on their positions, debate each candidateÔÇÖs pros and cons, and make their decision.

Except the Times endorsement was a failure. In part, thatÔÇÖs because of the editorial boardÔÇÖs decision to endorse both Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar, rather than make the hard choice of selecting one person. But The Weekly was also responsible for that failure. Asking audiences to watch a TV show and wait for the result mimics a reality-show stunt, which in itself is obnoxious, but ÔÇ£The EndorsementÔÇØ also failed to provide the basic framework of a decision-based reality show. There were few guidelines about the process, and little about the episode was compelling. These were flaws in the endorsement episode in particular but are symptomatic of a problem that has undermined nearly all of The Weekly: What could be a revelatory show about reporting and editorial decisions at the most prominent newsroom in the country has instead been superficial and myopic.

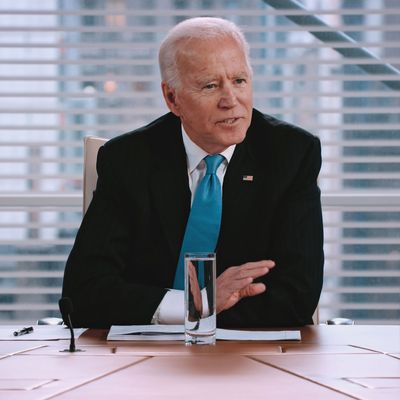

At the beginning of SundayÔÇÖs episode, Times deputy editorial-page editor Kathleen Kingsbury explains the basics of the endorsement process: The board will conduct an in-depth interview with each major Democratic candidate, which will help the members decide whom to endorse ahead of the primaries. Throughout the episode, thatÔÇÖs precisely what happens. Each candidate takes a turn entering a large boardroom, sitting at the head of a massive table, and answering questions.

But if The WeeklyÔÇÖs endorsement episode aimed to offer transparency into the boardÔÇÖs process, the candidate interviews didnÔÇÖt offer anything new. All the interviews were published in full before the episode aired, meaning the very brief excerpts that appear in The Weekly are much less than a full record of the conversations each candidate had with the board. The new information from The Weekly, what little of it there is, comes in even smaller snippets of conversation between the editorial-board members. ÔÇ£Maybe because IÔÇÖm from the Midwest,ÔÇØ Kingsbury says after Pete ButtigiegÔÇÖs interview, ÔÇ£but I find the Midwest affect and the way he talks about things to be very appealing.ÔÇØ ÔÇ£His tone,ÔÇØ Aisha Harris says, disagreeing, ÔÇ£thatÔÇÖs not what people want right now.ÔÇØ

Then the scene cuts to black, and itÔÇÖs on to a new candidate. What happened? Did anyone at the table respond to Harris and try to claim that ButtigiegÔÇÖs Midwestern persona might be more broadly appealing? Did others agree with her skepticism? Was that the most valuable takeaway from ButtigiegÔÇÖs interview? Is ÔÇ£toneÔÇØ a significant facet of how the editorial board judges candidates? It seems to have been high on the list of important qualities in other candidates as well: Jesse Wegman mentions that he likes WarrenÔÇÖs ÔÇ£fighting spirit,ÔÇØ although Serge Schmemann wonders whether WarrenÔÇÖs rhetorical chops ÔÇ£verge on being patronizing at times.ÔÇØ When Alex Kingsbury describes feeling comforted by Joe BidenÔÇÖs interview, Charlie Warzel cuts in. ÔÇ£This is such an uninspiring argument just in general,ÔÇØ he says. Warzel sees this as an urgent moment and chafes at the desire to endorse ÔÇ£a warm body that a lot of people can agree on.ÔÇØ

WarzelÔÇÖs point is telling because it doesnÔÇÖt quite fit with the comment that came before it. He seems to be responding to some bit of conversation we didnÔÇÖt see in the episode ÔÇö which is likely, because as the Times has reported, the board recorded ÔÇ£hoursÔÇØ of discussion that had to be condensed into a few interstitial minutes between each candidate. (And, unlike with the candidate interviews, the Times has not published full transcripts of the editorial-board discussion.)

But WarzelÔÇÖs point is also telling because we donÔÇÖt see the editorial board wrestle with it. There are almost no back-and-forth discussions of any substance. When it comes time to make the final decision, Kathleen Kingsbury similarly doesnÔÇÖt articulate any of her internal debate. ThereÔÇÖs no sense of how much she struggled with the choice to pick two people or what elements featured most strongly in her thinking. ThereÔÇÖs not even an explanation of whether she has the final say, whether the board gets to vote, or whether any other Times editors must approve the endorsement. The transparency offered by The Weekly is a false one, more an advertisement for the process than a clear window into the boardÔÇÖs thinking.

The same problem plagues all of The Weekly. The ostensible aim of the show is to be an inside-the-news view of the Times and its reporters, but the episodes neither present new information nor dive into the discussions that go into any editorial process. The episode that profiles Don McGahn includes many important names talking about him but creates no portrait of who McGahn really is. The Rudy Giuliani episode is just as frustrating. Episodes about more directly investigative reporting work a little better ÔÇö the one on the Johnson & Johnson baby-powder suit, the one about Breathalyzers ÔÇö but those too rely on asking questions and resist landing on answers. Instead, The WeeklyÔÇÖs additive value is entirely in nicely framed visuals and putting faces to the TimesÔÇÖ names. ItÔÇÖs true that The Weekly may be an entry point for viewers who prefer to consume news in TV format rather than as written reporting, but the episodes invariably feel less dense than the original reports. The show is like a film adaptation of a novel that assumes that merely depicting the characters onscreen provides a sufficient level of insight.

ItÔÇÖs probably not reasonable to expect a docuseries co-produced by a publication to offer any insightful, potentially critical look at that publication. (Leave that to documentaries like Page One and The Fourth Estate, which provide a more incisive documentary eye on their subjects.) But The WeeklyÔÇÖs problems are also an issue of format, which is clear when you compare it with the Times podcast The Daily. Like The Weekly, The Daily works as an inside view of the TimesÔÇÖ reporting, and the podcast is no more likely to be critical of its parent publication than the TV series is. But it does have a host, Michael Barbaro, whose role is to create the contextual analysis that The Weekly typically lacks. Barbaro asks reporters to connect their current stories to previous work theyÔÇÖve done, he pushes for clarification, and he creates a dialogue that often allows reporters to reveal more of themselves than is visible in the highly polished snippets of voice-over offered in The Weekly.

If Kathleen Kingsbury had been asked to explain her endorsement thinking to an interlocutor on The Weekly, it couldÔÇÖve been fascinating. If a host were responsible for ensuring that The Weekly offers something beyond the most superficial explanations, it couldÔÇÖve been a really valuable look at a significant moment in American journalism. Instead, it was just infuriating.