The animated Tokyo of Weathering With You is caught in the grip of a seemingly endless downpour. Rain sheets down on the waterlogged city with a dreary consistency, transforming its sidewalks into seas of puddles, and obscuring its citizens under slow-moving streams of umbrellas. On the news, the unrelenting precipitation gets described first as unseasonable, then as record-breaking, and finally, when it gives way to typhoon warnings and bursts of snow in August, as dangerous. But even when the storm gets severe enough to start driving people from their homes, it’s spoken about with a resigned acceptance that feels terribly familiar. It’s the acceptance that a recent misery might just be the new normal. “I feel sorry for children nowadays. We used to have beautiful springs and summers,” one character muses. The weather is the weather, and, regardless of how human behavior may have altered it, it has to be lived with. Unless, of course, you happen to find yourself with the power to change it, the way one of the characters in Weathering With You does — a miraculous talent that turns out to be accompanied by a terrible choice.

Weathering With You comes from writer/director Makoto Shinkai, whose body-swapping romance Your Name became a global phenomenon, the highest-grossing anime feature of all time. Like his monster 2016 hit, Shinkai’s latest is a teen love story shot through with touches of magical realism — in this instance, revolving around a young woman’s ability to temporarily cause the clouds to part and allow sunshine through. It brims with emotions and wears its watery heart on its sleeve, but it’s a decidedly minor-key, more melancholy affair than its predecessor; its characters contend with homelessness, being orphaned, sex work, and gun violence. To say that it’s an allegory about climate change feels both true and a little reductive. Maybe it’s more fair to call it one about young people contending with an awareness that their futures may have been sacrificed by the generations before them.

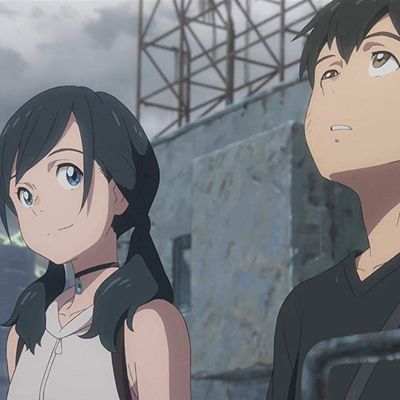

The film’s hero, Hodaka (Kotaro Daigo), is a 16-year-old runaway who’s fled to Tokyo from the isolated island on which he grew up. He’s got some savings, but not much of a plan — too young to legally work, he crashes in a manga café and asks advice from internet forums. He meets Hina (Nana Mori) when she gives him a free burger at the fast-food restaurant where she works. Later, to her annoyance, Hodaka attempts to “rescue” Hina from some men in the red light district. She’s a teenager herself, one who lives alone with her younger brother Nagi (Sakura Kiryu), and they need money. But she’s harboring a secret, one that she shows Hodaka up on the roof of an abandoned building. When she prays, the rain briefly gives way to bright sunlight — a gift she acquired after a mysterious incident when she was keeping watch over her dying mother the year before. Hodaka, who’s since found himself a crash pad with a disreputable but good-hearted writer named Keisuke (Shun Oguri), thinks they can monetize this ability, and the two set up a website and go into business summoning sunshine for around $30 a pop.

This is, to put it lightly, a busy set-up. Like Your Name, Weathering With You toggles between the mystical (a foreboding legend about a weather maiden) and the mundane (Hodaka retrieving his passed-out-drunk boss from a bar), but with an amount of detail that can be disorienting. Still, the lived-in tangibility of its Tokyo, which is portrayed with immense fondness and little romanticism, is what makes the film’s best trick so effective. When Hina prays, the sun spills through the clouds, glinting off windshields, turning the sides of skyscrapers golden, creating islands of light in the cityscape where suddenly life seems more bearable. Shinkai has a more commercial sensibility than that of the other anime auteurs, like Hayao Miyazaki and Satoshi Kon, whose work has managed to break through into the American mainstream. (Shinkai is, among other things, not shy about product placement.) But at his best, he’s capable of evoking a sense of ecstatic yearning that feels uniquely his, and also uniquely adolescent. Weathering With You comes across as YA in the best possible sense, in that the film’s audience never has to stretch too far to get back to the feeling of being the age of its characters.

They’re characters who struggle for sanctuary in a present that’s less unfriendly than indifferent. Hina’s ability, and the price it exacts, serve as an expression of both her personal martyrdom and of a generational kind — she’s essentially given the opportunity to turn back the clock for everyone, at her own expense. There’s a touch of “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” to Weathering With You that makes the direction it ultimately veers off into both surprisingly abrupt and darkly pragmatic. It’s also, in its own way, optimistic. Maybe, the film suggests, before anyone can think about saving the world, they have to figure out how to live in it.