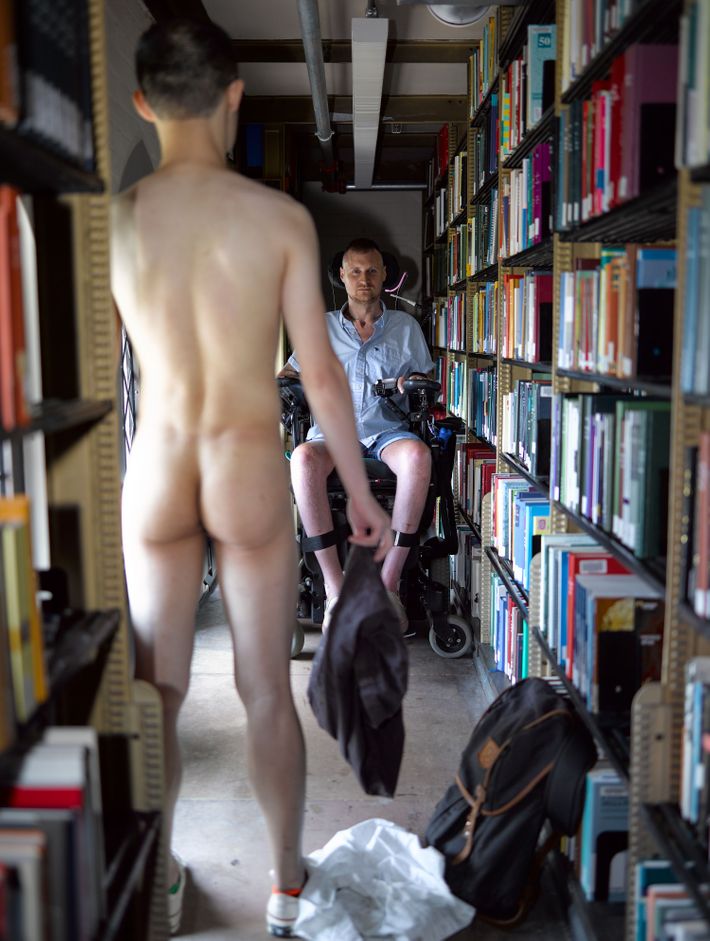

The photographer Robert Andy Coombs cannot hold his own camera. Mostly paralyzed from the shoulders down after a trampoline accident at age 21, he relies on assistance, and his art takes time to produce. He uses a wheelchair and controls his digital camera via a joystick operated by his mouth. His is among the most unshakable new work, by a new voice, I have come across in years. At the end of 2019, I included Coombs on a top-ten list of the yearÔÇÖs best; in the month since, I havenÔÇÖt been able to get his work out of my head.

CoombsÔÇÖs photographs give us a gorgeous orchidology of sexual desire. In them, you can see crescendos of pleasure, helplessness, fear, and taboo, all laced with a tragic-comic self-mocking and a demanding reclamation of the disabled body as autonomous ÔÇö that is, flush with agency and physical hunger. Male sexual desire is a very complicated terrain to traverse these days; with each photograph, Coombs gives us a new way in.

In the lushly baroque, florid-colored theatricality of the photograph Ascension to the Throne, the naked Coombs, 33, with a flesh-colored suprapubic catheter inserted into his midsection, is situated in a partly darkened basement. HeÔÇÖs held aloft by three other naked men ÔÇö a profile of his purpling amethyst body, supple, soft. With dramatic Caravaggesque lighting and the figures highly posed, Coombs is being placed on yet another naked figure, this one on all fours, whose rear is to the viewer. A similar picture in the same basement features Coombs being held in a sitting position by these naked men over the same figure. Coombs gazes at us, and a strange reversal takes place. HeÔÇÖs not just a naked Lady Godiva rider; the body of Coombs is some Christ in Majesty. In fact, the composition echoes ManetÔÇÖs 1864 Dead Christ With Angels. The powerlessness of Coombs has shifted to power; he rivets our attention, looking directly at us as if to say, ÔÇ£Yes, this is meÔÇØ ÔÇö a servant and a master. The image isnÔÇÖt filled with pathos, pain, pity. ThereÔÇÖs no shame here or sideshow spectacle. As Mapplethorpe did with formalism and ideas of beauty, dignity, and art, Coombs redefines these things ÔÇö rescuing them from banishment, guilt, and criminality.

None of this work is cheaply shocking or comes off as porn. ItÔÇÖs portraiture, evidence, bearing witness, activism. References abound to Goya, Vel├ízquez, and a whole history of Western painting. I recall an image on his Instagram account of Coombs left alone on the beach. It sent shivers down my spine. Of course, as with numerous queer and disabled artists who post their work on Instagram, CoombsÔÇÖs account was canceled. After I helped reinstate it, the account was canceled again. (You can follow him at @rac.backup.)

Two references may be useful in grasping the deep content in Coombss work. First, Rembrandts famous The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632). In a scene lit by racking light, a group of black-suited men witness a doctor performing an autopsy. While the corpse  its viscera, deadness, and power  is at the center of the image, no one actually looks at the body. Its rendered a nonbeing, a thing. This has real parallels to Coombss project. Instead of looking at the body, most of the men in Rembrandts painting peer at a textbook in the corner  as if inert, impaired, dead flesh is too much, not reasonable enough, to gaze upon. This metaphor of seeing and not seeing is amplified by the narrative of imagined contagion that is central to Coombss art. He told me that some men are scared of their inevitable fragile mortality and are deathly afraid of me  like theyre going to catch something and become crippled like me forever. Indeed, I was afraid of him when I first saw his work. In fact, weve never met; he invited me to the studio a year ago and I let it go. Ableist bias, shame, and fear is deeply inculcated.

The second useful reference is Charlie ChaplinÔÇÖs The Great Dictator, in which Chaplin plays both a Jewish barber and the dictator Hynkel. Even in the looming shadow of the Holocaust, we laugh with Chaplin at everyoneÔÇÖs plight and folly while also critiquing it. Coombs has this precious gift, opening his world and showing that it is also ours. He does this, like Chaplin, by short-circuiting our defenses with laughter. On top of all that, it helps to imagine Coombs as another kind of Cindy Sherman, always the focal point of his work. However, while Sherman is not really visible and a cipher in her art, Coombs is always out in the world or on location and so is playing the role both of the corpse and the mirror, the dictator and the Jew.

Always center stage.

Pull back, and CoombsÔÇÖs art addresses different communities and time frames. For him to do anything entails the assistance or participation of others, lots of preplanning, and research into every condition. In this way, time moves much slower for people with disabilities and calls into question the very idea of ÔÇ£productivityÔÇØ and how we define artistic production and growth. Nonstop activity is out of the question, which makes the modernist myth of the lone protean genius a complicated one for Coombs.

The sex depicted in CoombsÔÇÖs work has almost never been depicted in the history of art. As he puts it, ÔÇ£There are people with disabilities who have no idea how their body even works sexually because health-care professionals donÔÇÖt cover sexuality as part of their practice. People with disabilities are left to figure out everything on their own. Society doesnÔÇÖt view us as sexual human beings. My work is just scratching the surface of whatever ÔÇÿdisabled sexÔÇÖ looks like ÔǪ We need to start shifting the conversation from ÔÇÿHow do you have sex?ÔÇÖ to ÔÇÿWhat sexual acts do you enjoy?ÔÇÖÔÇàÔÇØ

Robert Andy Coombs is showing at the Palm Springs Art Museum through March 29.

*This article appears in the February 3, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!