This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

I worked at various start-ups for eight years beginning in 2010, when I was in my early 20s. Then I quit and went freelance for a while. A year later, I returned to office life, this time at a different start-up. During my gap year, I had missed and yearned for a bunch of things, like health care and free knockoff Post-its and luxurious people-watching opportunities. (In 2016, I saw a co-worker pour herself a bowl of cornflakes, add milk, and microwave it for 90 seconds. I’ll think about this until the day I die.) One thing I did not miss about office life was the language. The language warped and mutated at a dizzying rate, so it was no surprise that a new term of art had emerged during the year I spent between jobs. The term was parallel path, and I first heard it in this sentence: “We’re waiting on specs for the San Francisco installation. Can you parallel-path two versions?”

Translated, this means: “We’re waiting on specs for the San Francisco installation. Can you make two versions?” In other words, to “parallel-path” is to do two things at once. That’s all. I thought there was something gorgeously and inadvertently candid about the phrase’s assumption that a person would ever not be doing more than one thing at a time in an office — its denial that the whole point of having an office job is to multitask ineffectively instead of single-tasking effectively. Why invent a term for what people were already forced to do? It was, in its fakery and puffery and lack of a reason to exist, the perfect corporate neologism.

The expected response to the above question would be something like “Great, I’ll go ahead and parallel-path that and route it back to you.” An equally acceptable response would be “Yes” or a simple nod. But the point of these phrases is to fill space. No matter where I’ve worked, it has always been obvious that if everyone agreed to use language in the way that it is normally used, which is to communicate, the workday would be two hours shorter.

In theory, a person could have fun with the system by introducing random terms and insisting on their validity (“We’re gonna have to banana-boat the marketing budget”). But in fact the only beauty, if you could call it that, of terms like parallel path is their arrival from nowhere and their seemingly immediate adoption by all. If workplaces are full of communal irritation and communal pride, they are less often considered to be places of communal mysticism. Yet when I started that job and began picking up on the new vocabulary, I felt like a Mayan circa 1600 BCE surrounded by other Mayans in the face of an unstoppable weather event that we didn’t understand and had no choice but to survive, yielding our lives and verbal expressions to a higher authority.

Anyhow, I left the parallel-path job after six months — unrelated to the standard operating language, although I used a wad of it in my resignation.

In January, a very good memoir called Uncanny Valley was published. The author, Anna Wiener, moved to San Francisco from Brooklyn around 2014 to work at a mobile-analytics start-up, and one of the book’s many pleasures is how neatly it bottles the scent of moneyed Bay Area in the mid-2010s: kombucha, office dog, freshly unwrapped USB cable. Wiener talks about the lofty ambitions of her company, its cushy amenities, the casual misogyny that surrounds her like a cloud of gnats. The book hit me in two places. One of them was a tender, heart-adjacent place that remembered growing up in San Francisco, with its fog-ladled neighborhoods and football fields of fleece. The other was closer to my liver, where bile is manufactured. This was the part of me that remembered working at places much like the one Wiener describes — jobs that provided money to pay rent in a major urban area while I freelanced for magazines and websites that did not. Writing, it turns out, is an economically awkward skill. Despite the fact that it can’t yet be outsourced or performed cheaply by robots, it isn’t worth much. In the case of Anna Wiener (and maybe only Anna Wiener), this is a good thing, because it forced her to embed in a landscape that cried out for narration and commentary.

The status pyramid at most start-ups is roughly this: The C-suite sits at the pinnacle, followed by senior data and tech people, followed by non-senior data and tech people, followed by everyone else except customer service, and then, at the very bottom, customer service. Which, by the way, has been rechristened “customer support” or “customer experience” at most companies — as though the word service might remind the college graduates recruited for these roles that they will in fact spend their days pacifying irritable consumers over phone, chat, text, and email. Wiener worked in customer support.

Being the lowliest worm at a company offers observational advantages in that it renders a person invisible. Wiener describes watching her peers attend silent-meditation retreats, take LSD, discuss Stoicism, and practice Reiki at parties. She tries ecstatic dance, gulps nootropics, and accepts a “cautious, fully-clothed back massage” from her company’s in-house masseuse. She encounters a man who self-identifies as a Japanese raccoon dog. She’s a participant and an ethnologist; she’s impressed and revulsed.

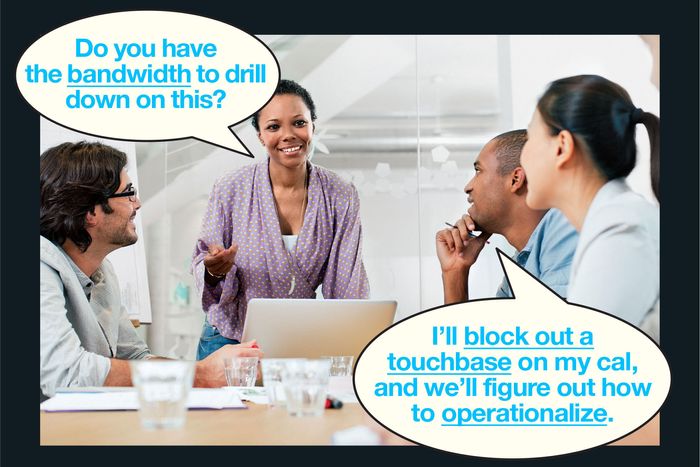

Wiener writes especially well — with both fluency and astonishment — about the verbal habits of her peers: “People used a sort of nonlanguage, which was neither beautiful nor especially efficient: a mash-up of business-speak with athletic and wartime metaphors, inflated with self-importance. Calls to action; front lines and trenches; blitzscaling. Companies didn’t fail, they died.” She describes a man who wheels around her office on a scooter barking into a wireless headset about growth hacking, proactive technology, parallelization, and the first-mover advantage. “It was garbage language,” Wiener writes, “but customers loved him.”

I know that man, except he didn’t ride a scooter and was actually a woman named Megan at yet another of my former jobs. What did Megan do? Mostly she set meetings, or “syncs,” as she called them. They were the worst kind of meeting — the kind where attendees circle the concept of work without wading into the substance of it. Megan’s syncs were filled with discussions of cadences and connectivity and upleveling as well as the necessity to refine and iterate moving forward. The primary unit of meaning was the abstract metaphor. I don’t think anyone knew what anyone was saying, but I also think we were all convinced that we were the only ones who didn’t know while everyone else was on the same page. (A common reference, this elusive page.)

In Megan’s syncs, I found myself becoming almost psychedelically disembodied, floating above the conference room and gazing at the dozen or so people within as we slumped, bit and chewed extremities, furtively manipulated phones, cracked knuckles, examined split ends, scratched elbows, jiggled feet, palpated stomach rolls, disemboweled pens, and gnawed on shirt collars. The sheer volume of apathy formed an energy of its own, like a mudslide. At the half-hour mark of each hour-long meeting, our bodies began to list perceptibly toward the door. It was like the whole room had to pee. When I tried to translate Megan’s monologues in real time, I could feel my brain aching in a physical manner, the way it does when I attempt to understand blockchain technology or do my taxes.

I like Anna Wiener’s term for this kind of talk: garbage language. It’s more descriptive than corporatespeak or buzzwords or jargon. Corporatespeak is dated; buzzword is autological, since it is arguably an example of what it describes; and jargon conflates stupid usages with specialist languages that are actually purposeful, like those of law or science or medicine. Wiener’s garbage language works because garbage is what we produce mindlessly in the course of our days and because it smells horrible and looks ugly and we don’t think about it except when we’re saying that it’s bad, as I am right now.

But unlike garbage, which we contain in wastebaskets and landfills, the hideous nature of these words — their facility to warp and impede communication — is also their purpose. Garbage language permeates the ways we think of our jobs and shapes our identities as workers. It is obvious that the point is concealment; it is less obvious what so many of us are trying to hide.

Another thing this language has in common with garbage is that we can’t stop generating it. Garbage language isn’t unique to start-ups; it’s endemic to business itself, and the form it takes tends to reflect the operating economic metaphors of its day. A 1911 book by Frederick Winslow Taylor called The Principles of Scientific Management borrows its language from manufacturing; men, like machines, are useful for their output and productive capacity. The conglomeration of companies in the 1950s and ’60s required organizations to address alienated employees who felt faceless amid a sea of identical gray-suited toilers, and managers were encouraged to create a climate conducive to human growth and to focus on the self-actualization needs of their employees. In the 1980s, garbage language smelled strongly of Wall Street: leverage, stakeholder, value-add. The rise of big tech brought us computing and gaming metaphors: bandwidth, hack, the concept of double-clicking on something, the concept of talking off-line, the concept of leveling up.

One of the most influential business books of the 1990s was Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma. Christensen is responsible for the popularity of the word disruptive. (The term has since been diluted and tortured, but his initial definition was narrow: Disruption happens when a small company, such as a start-up, targets a limited segment of an incumbent’s audience and then uses that foothold to attract a bigger segment, by which point it’s too late for the incumbent to catch up.) The metaphors in that book had a militaristic strain: Firms won or lost battles. Business units were killed. A disk drive was revolutionary. The market was a radar screen. The missilelike attack of the desktop computer wounded minicomputer-makers. Over the next decade and a half, the language fully migrated from combative to New Agey: “I am now a true believer in bringing our whole selves to work,” wrote Sheryl Sandberg in Lean In, urging readers to seek their truth and find personal fulfillment. In Delivering Happiness, Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh described making conscious choices and evolving organically. In The Lean Startup, Eric Ries pitched his method as a movement to unlock a vast storehouse of human potential. You can always track the assimilation of garbage language by its shedding of scare quotes; in 1911, “initiative” and “incentive” were still cloaked in speculative punctuation.

At my own workplaces, the New Age–speak mingled recklessly with aviation metaphors (holding pattern, the concept of discussing something at the 30,000-foot level), verbs and adjectives shoved into nounhood (ask, win, fail, refresh, regroup, creative, sync, touchbase), nouns shoved into verbhood (whiteboard, bucket), and a heap of nonwords that, through force of repetition, became wordlike (complexify, co-execute, replatform, shareability, directionality). There were acronyms like RACI, which I learned about in this way:

CO-WORKER: Going forward, we’ll be using a RACI for all projects.

MOLLY: What’s a RACI?

CO-WORKER: RACI stands for “Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed.” The RACI will be distributed around so that we’re all aligned and on the same page.

ME: But what is this thing, like, physically? Is it a chart?

CO-WORKER: It’s hard to explain.

I never found out what a RACI was because we never ended up using one, but according to its Wikipedia page, it’s a “matrix” with over a dozen popular variations, including RATSI. I can imagine a world in which all these competing references might combine into a jaggedly interesting verbal landscape, but instead they only negated each other, the way 20 songs would if you played them at the same time.

And yet it should be possible to gaze into this alphabet soup and divine patterns. Our attraction to certain words surely reflects an inner yearning. Computer metaphors appeal to us because they imply futurism and hyperefficiency, while the language of self-empowerment hides a deeper anxiety about our relationship to work — a sense that what we’re doing may actually be trivial, that the reward of “free” snacks for cultural fealty is not an exchange that benefits us, that none of this was worth going into student debt for, and that we could be fired instantly for complaining on Slack about it. When we adopt words that connect us to a larger project — that simultaneously fold us into an institutional organism and insist on that institution’s worthiness — it is easier to pretend that our jobs are more interesting than they seem. Empowerment language is a self-marketing asset as much as anything else: a way of selling our jobs back to ourselves.

In August, WeWork — recently rebranded as the We Company — submitted its prospectus to the Securities and Exchange Commission. The document is just under 200,000 words long, or nearly the length of Moby-Dick, and it reads like something a person wrote in the middle of an Adderall overdose with a gun to his head. Here’s how the company describes itself on page one:

We are a community company committed to maximum global impact. Our mission is to elevate the world’s consciousness. We have built a worldwide platform that supports growth, shared experiences and true success.

You can probably imagine the rest. In the words of a lecturer at Harvard Business School, the prospectus “reads like a Marianne Williamson self-help book,” which might be insulting to Marianne Williamson. As with any public-facing statement issued by a company, the prospectus maps the distance between what the company is and how it sees itself. What is beautiful — almost spiritual in its grandeur! — about WeWork is not the vastness of the distance but how easy it is to measure. WeWork’s real-estate arbitrage can be summarized in plain English, yet the prospectus is so baroquely worded that it requires a kind of medieval exegesis — a willingness to pore over the text, assess its truth claims, elaborate on its explanations, and unmask its hidden values. In its fidelity to incoherence, WeWork’s majestic PDF revealed a now-obvious truth about the organization, which is that its ratio of ingenuity to bullshit — a ratio present in every organization and, indeed, every human — was tipped too far in the wrong direction.

The collision of corporate self-actualization with business realities was at the center of a story about the luggage company Away that came out in December. (Disclosure: I worked with both of the Away founders in the early 2010s, before the company existed, at a different company. They seemed nice.) A piece in The Verge by Zoe Schiffer reported on Away’s work environment, which looked like a mixture of punishing hours, dangled career opportunities, and an “until morale improves, the beatings will continue” theory of management cloaked in wretchedly obtuse language. A 9 a.m. message from the company’s CEO, Steph Korey, to customer-experience employees went like this:

I know this group is hungry for career development opportunities, and in an effort to support you in developing your skills, I am going to help you learn the career skill of accountability … To hold you accountable — which is a very important business skill that is translatable to many different work settings — no new [paid time off] or [work from home] requests will be considered from the 6 of you … I hope everyone in this group appreciates the thoughtfulness I’ve put into creating this career development opportunity and that you’re all excited to operate consistently with our core values to solve this problem and pave the way for the [customer experience] team being best-in-class when it comes to being Customer Obsessed. Thank you!

You could run down Korey’s leaked messages — this and others — with a checklist. Did she revert to the passive voice in a way that seemed to divest herself of responsibility? Yes. Did she Capitalize words Arbitrarily? Yes. Did she type phrases like “utilize your empowerment”? She did.

The internet went nuts. Here, finally, was proof of a maddening experience that many people had undergone: the weaponization of language by a person in power that bewildered, embarrassed, and penalized the people beneath her. Did Korey really believe that withholding paid time off from lower-level employees counted as a career opportunity? Was her mind a ticker tape of sentences like this, or had she run it through an internal executive-translation plug-in?

There’s an early Edith Wharton story where a character observes the constraints of speaking a foreign tongue: “Don’t you know how, in talking a foreign language, even fluently, one says half the time, not what one wants to, but what one can?” To put it another way: Do CEOs act like jerks because they are jerks, or because the language of management will create a jerk of anyone eventually? If garbage language is a form of self-marketing, then a CEO must find it especially tempting to conceal the unpleasant parts of his or her job — the necessary whip-cracking — in a pile of verbal fluff. Korey wouldn’t have sounded any nicer if she’d said exactly what she likely meant (“I am disappointed in your work, and there will be consequences, fair or not”), but I doubt she would have gotten in trouble for saying it. Meanness doesn’t inflame people as much as hypocrisy does.

As the leaked Slacks make clear, Korey, as well as her employees, were working under the new conditions of surveillance-state capitalism (or, from the company’s perspective, a culture of “inclusion and transparency”). One reason for the uptick in garbage language is exactly this sense of nonstop supervision. Employers can read emails and track keystrokes and monitor locations and clock the amount of time their employees spend noodling on Twitter. In an environment of constant auditing, it’s safer to use words that signify nothing and can be stretched to mean anything, just in case you’re caught and required to defend yourself.

And so Korey’s problem was less her strategy than her execution. Away was founded by two women who saw, in a climate where Glossier was thriving and a book called #GIRLBOSS was a best-seller, that the language of empowerment could be a terrific brand asset for, of all things, a suitcase manufacturer. It made sense that Korey spoke to her employees in terms of opportunity and growth. Her mistake was in trying to extract their gratitude for it. I hope everyone in this group appreciates the thoughtfulness I’ve put into creating this career-development opportunity.

Language had gotten other people in trouble at Away, too. About a year earlier, a handful of employees started a private Slack channel to talk candidly about being marginalized at the company — using, presumably, indefensible non–garbage language. The channel was reported, and six people were fired. For Korey’s misdeeds, she resigned as CEO, suffered a few weeks of embarrassment, then changed her mind and reclaimed her old job. Nobody observing the two outcomes could mistake the lesson here.

In 2011, I was dropping printouts on a co-worker’s desk when I spotted something colorful near his laptop. It was a small foil packet with a fetching plaid design.

My co-worker’s assistant was sitting nearby. “Caroline,” I said, “do you know what this is?”

“Yeah,” she said. “Jim belongs to some kind of runners’ club that sends him a box of competitive running gear every month.”

The front of the plaid packet said UPTAPPED: ALL NATURAL ENERGY. The marketing copy said, “For too long athletic nutrition has been sweetened with cheap synthetic sugars. The simplicity of endurance sports deserves a simple ingredient — 100% pure, unadulterated, organic Vermont maple syrup, the all-natural, low glycemic-index sports fuel.”

It was a packet of maple syrup. Nothing more. Whenever I hear a word like operationalize or touchpoint, I think of that packet — of some anonymous individual, probably with a Stanford degree and a net worth many multiples of my own, funneling maple syrup into tubelets and calling it low-glycemic-index sports fuel. It’s not a crime to try to convince people that their favorite pancake accessory is a viable biohack, but the words have a scammy flavor. And that’s the closest I can come to a definition of garbage language that accounts for its eternal mutability: words with a scammy flavor. As with any scam, the effectiveness lies in the delivery. Thousands of companies have tricked us into believing that a mattress or lip-gloss order is an ideological position.

In 2016, Jessica Helfand, an author and a founder of the website Design Observer, was invited to teach at Yale School of Management. The idea was that Helfand could instruct grad students in the art of creative thinking, which they could then use to start companies and make money. She immediately developed a contact allergy to the way her students spoke. “It started the first week I was there. After the lecture, a student said, ‘Well, my takeaway is …,’ and I thought, ‘Takeaway’ is what you do with food in London. Maybe instead of a takeaway, you could sit with the ideas for a while and just … think.” Helfand compiled a list of commonly bandied-about words and divided them into categories like Hyphenated Mash-ups (omni-channel, level-setting, business-critical), Compound Phrases (email blast, integrated deck, pain point, deep dive) and Conceptual Hybrids (“shooting” someone an email, “looping” someone in). All of these were phrases with “aspirational authority,” she told me. “If you’re in a meeting and you’re a 20-something and you want to sound in the know, you’re going to use those words.” It drove Helfand nuts. This wasn’t a teaching position; it was a deprogramming job. She left before the contract was up.

The problem with these words isn’t only their floating capacity to enrage but their contaminating quality. Once you hear a word, it’s “in” you. It has penetrated your ears and entered your brain, from which it can’t be selectively removed. Sometimes a phrase will pop into my head that I haven’t heard in years — holistic road map — and I will feel as if someone just told me that in July 2016, I ate a bowl of soup that contained a booger. I’m overcome with aversion; I’m too late to do anything.

This hints at the futility of writing about irritating words. Usage peeves are always arbitrary and often depend as much on who is saying something as on what is being said. When Megan spoke about “business-critical asks” and “high-level integrated decks,” I heard “I am using meaningless words and forcing you to act like you understand them.” When an intern said the same thing, I heard someone heroically struggling to communicate in the local dialect. I hate certain words partly because of the people who use them; I can’t help but equate linguistic misdemeanors with crimes of the soul. Nietzsche’s On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense makes swift, excoriating work of language as a whole, but it exactly predicts the extravagant inanity of garbage language:

A mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms — in short, a sum of human relations which have been enhanced, transposed, and embellished poetically and rhetorically, and which after long use seem firm, canonical, and obligatory to a people: truths are illusions about which one has forgotten that this is what they are; metaphors which are worn out and without sensuous power; coins which have lost their pictures and now matter only as metal, no longer as coins.

He proposed (I’d argue) that we just give up on functional speech altogether — drop the charade that our personal realities share a common language. Choosing to speak poetically (by which he meant intentionally calling things what they are not) was his ironic solution. Language is always a matter of intention. No two people could have less in common than when they are saying the same thing, one sincerely and one with snark. And so with every exchange, you have to acknowledge a reality where words like optionality and deliverable could be just as solid as blimp and pretzel. What happens if you ask a Megan or a Steph Korey or an Adam Neumann what they mean? I imagine a box with a series of false bottoms; you just keep falling deeper and deeper into gibberish. The meaningful threat of garbage language — the reason it is not just annoying but malevolent — is that it confirms delusion as an asset in the workplace.

*This article appears in the February 17, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!