I was desperate to be hired as the cinematographer on Big. The producer, Bobby Greenhut, was the best in New York, producing many of the movies filmed there. If I could get in his good graces, maybe I could work in my hometown more often. Greenhut had a wicked sense of humor. When describing Gordon Willis’s very dark lighting on the movies Greenhut produced for Woody Allen, Greenhut quipped, “Gordon Willis lights for radio.”

I had been the cinematographer on two low-budget Coen films — Blood Simple and Raising Arizona — when I went for an interview. The Coen Brothers movies had gotten a lot of attention, so David Gersh, my agent, was able to arrange a meeting with Penny Marshall, Big’s director.

I arrived at Big’s office on 57th Street and was escorted into a room I could barely see into due to the harsh direct rays of sun coming through the window, backlighting Penny’s cigarette smoke. Sitting behind Penny was a man who smiled at me but neither introduced himself nor spoke. He was dressed in blue New York Giants football gear down to his blue sneakers. He looked like a Smurf.

I assumed the guy was Penny’s cousin who was either mentally challenged or at least shy and a tad off. In the foreground Penny started to tell me about the look she wanted for Big: When the kid is a kid, the camera should be low and naive. When he is transformed into an adult, the camera should be higher and more sophisticated. I listened and tried not to interrupt. I really wanted the job.

This is what I knew: steadfast rules of cinematography never work.

It was great that Penny had thought about how to tell her story visually, but I knew it wasn’t going to work out the way she saw it. And I wasn’t sure how to manifest a camera’s naïveté or sophistication.

Penny put out one last cigarette and mumbled, “Well, whaddaya think?”

Here’s what I said: “Would it be okay if I just make it look nice?”

Penny turned to the Smurf in the back of the room and in an over the shoulder mutter said,

“Nice would be good.”

The blue guy got out of his chair, put out his hand, and said,

“Nice meeting you. We’ll be in touch.”

“Nice meeting you, too. Hey. Who are you?”

“Bobby Greenhut,” Greenhut chuckled as he led me out the door.

I had blown my interview.

“Would it be okay if I just made it look nice?” doesn’t inspire confidence, although truthfully, most films fall short.

I was working on a SONY industrial for Howie Meltzer and Jon Klee. We were prelighting the stage for tomorrow’s puppet work when my cell phone rang.

“Hello?”

“Sonnenfeld? This is Greenhut.”

“Hi, Bobby. What’s up?”

“I was walking to work this morning, and I realized we start filming in ten weeks and we still don’t have a cinematographer so I said to myself, ‘Why not just hire that idiot Sonnenfeld?’”

“Ya know, Bobby. Thank you very much, but I don’t want to be hired on those terms.”

“What are you talking about? I’m offering you the job.”

“Not as that idiot Sonnenfeld. If you want to hire me, let’s have another interview so you can hire that really smart guy Sonnenfeld.”

“Are you serious?”

“I want another interview.”

“You know, Ba, you’re a little nuts. All right. Can you come up to the office right now?”

I was done pre lighting and made my way from Mother’s Stages, an old mansion in the East Village that had been converted to small soundstages, up to 57th Street.

As I got off the elevator and into the production’s bull pen, Greenhut came out of his office and yelled across the room,

“I just got off the phone with the studio. They said hire the cheapest cameraman you can find.”

“That I can do. As long as I’m not the idiot Sonnenfeld.”

“Great. You’re hired, Not Idiot Sonnenfeld.”

A few weeks later, 20th Century Fox shut down Big. Barry Diller, the chairman, didn’t want to make the movie with Penny’s first choice for the lead, Robert De Niro. He wanted to wait for Tom Hanks, who had just started another film. I went to L.A. and shot Throw Momma From the Train with Danny DeVito while Hanks fulfilled his previous commitment.

After finishing Throw Momma, I was back in New York, starting to work on Big.

Penny and I liked each other as people, but she truly disliked me as her cinematographer. We came from very different ways of working. Her expertise was acting and comedy. My strength was visual storytelling. It could have been a dynamic partnership, but that’s not what happened.

Penny didn’t like to make decisions and wanted as many options as possible. I came from film school, where each eleven minute roll of film, from raw stock through developing, cost several hundred dollars. For a film student, the solution was to preplan the edit and make every decision before you started to roll very expensive film.

I discovered just how much Penny didn’t like to make decisions on the first day of filming, which was a one-night shoot at Rye Playland. We were filming in the summer, and our nights were relatively short.

The scene involved Tom Hanks and Elizabeth Perkins. During preproduction we filmed two hair and makeup tests with Elizabeth so Penny could decide if Perkins should be a blonde or redhead. Normally, these choices are made many weeks before filming so the wardrobe and makeup people can select outfits and makeup that complement the chosen hair color.

The evening before our first day of filming, Greenhut called Penny and me into his office.

“Pen. We start filming tomorrow night. What’s it going to be? Blonde or redhead?”

“I don’t know,” Penny whined.

“Barry didn’t do a good job shooting the tests.”

“Well, Pen. You’re going to have to decide,” smiled Greenhut.

“Okay,” Penny mumbled.

“We’ll film it both ways.”

So, the first night of Big we filmed every angle of the scene with Elizabeth as a blonde and then a redhead. Because of the time required to switch out wigs and change her makeup for each hair color — for every camera angle — we decided it would be faster to film every shot of Elizabeth as a blonde, then go back and refilm every single setup except for Hanks’s close-ups as a redhead. We had a million tape marks on the ground with notes for where the camera was, where each light was, so we could quickly redo every shot.

During the filming of Big I discovered how Depends adult diapers worked. I rarely leave the set, and I don’t think any crew member should either. It would drive me crazy when I needed an additional light or wanted to add a piece of track to a dolly move, and I’d ask, “Where’s Rusty? Where’s Dennis?” and some crew member would say, “In the bathroom, sir.”

“Sir” is crew code for asshole, by the way.

I knew the boys were really on the pay phone with their broker or taking a quick nap, and I wanted to put a stop to it. Making the crew wear diapers might be the solution.

One weekend about halfway through the show I went to my local East Hampton IGA and bought a box of Depends adult diapers. I took off my pants and underwear, put on a set of Depends, and, thank God, stepped into the bathtub and peed. That’s when I discovered what Depends don’t do. It turns out they’re not designed for full‑on urination, so much as an occasional dribble. As the urine rapidly cascaded down my leg — those were the days — I said to myself, “Good to know.”

Another example of Penny’s indecision was in the now famous scene of Hanks and Perkins taking a limo ride through New York. The night of filming there were three grip and electric crews rigging three different cars with lights and cameras.

“Penny. You’ve had all of preproduction and eight weeks of shooting to decide. Is it the Subaru, the Corvette, or the limo?” Greenhut asked, as he pointed at three cars lined up in a row.

Penny had liked the Subaru XT because it had a colorful dashboard. She liked the Corvette because it was a convertible, and Josh, Hank’s character, would have liked a Vette. And, finally, we had the limo.

“What does Barry think?” asked Penny.

“The limo.”

“Okay. The limo,” Penny mumbled.

Then she added:

“Just remember. I said it was a bad idear.”

“Wait. Pen. Which would you prefer?”

“No. No. You said the limo. I’m just saying it’s a bad idear.”

Before I could respond, Bobby put his arm out in front of me to stop any further discussion and announced:

“It’s the limo, guys. Stop rigging the Vette and other thing.”

For Hanks’s company’s Christmas party, Penny asked the prop person to have caviar, knowing Tom would be brilliant in how shocked and disgusted he was by the taste. She also asked for baby corn, so that Tom could pick up the little pickled appetizer and eat it like it was a corn on the cob. Penny really knew where a joke was. She just didn’t like making hard decisions and didn’t like my visual style.

Penny and I got very little sleep. After filming for at least fourteen hours, we would drive to DuArt, our film lab, stand in the lobby for twenty minutes waiting for the elevator — every film lab in New York had shockingly slow elevators — and then watch literally two hours of 35mm projected dailies. Many people slept. Greenhut had a party-size red cup of Dewars handed to him at the screening room door. After dailies — sixteen hours into our day — Pen and I would be driven back to her apartment, where we discussed the angles for the next day.

Early Monday morning of the second week, we were setting up for a shot in young Josh’s neighborhood in New Jersey, when Penny’s driver arrived with her daily breakfast of a dozen White Castle hamburgers and a carton of Marlboros.

Penny, burger in her mouth, cigarette attached to her lower lip, squinted past the haze of smoke and mumbled,

“I tried to fi‑a you this weekend, but they wouldn’t let me.”

“Who wouldn’t, Pen? Who wouldn’t let you fire me?”

“They wouldn’t.”

“Pen, you should have any cameraman you want. If you don’t want me, you should get someone else. I’ll understand.”

“No. They said I can’t fi‑a you.”

“I’m sorry, Pen.”

“I called Danny. He says you’re good, but I don’t think so.”

DeVito and I loved working together on Throw Momma From the Train, and he was a fan of my visual style. Danny was a friend of Penny’s, so it made sense she would have given him a call.

“I don’t know what to tell ya, Pen. I’m really sorry.”

“No. It’s okay. It’s just that you’re not very good.”

Somehow, we got through another eleven weeks of filming. On schedule. There are dozens of stories too painful to tell, so I’ll only give a few more.

Hanks’s character works at a toy company. Robert Loggia’s character was the president of the firm. We filmed the scene where Hanks meets cute with Elizabeth Perkins using a big crane — a twenty-three-foot giraffe with a remote head. The camera pulls Elizabeth and Robert down a hallway as they chat. Then the crane starts to pull away, booming up higher and higher. As the camera comes to a stop, high angle tilted down, we see Hanks walking along the opposite corridor, ninety degrees from Loggia and Perkins. At the intersection they crash into each other. Loggia falls, Perkins’s papers fly everywhere, and the romance is on.

Between the beginning of the shot, when Perkins and Loggia are walking and talking, until the time they crash into Hanks, there is no coverage. The shot plays out as one continuous piece of acting. If anything goes wrong before the crash, call cut, because you can’t use the take. Plain and simple.

Penny, as was her want, was on take fifteen.

Loggia limps up to Penny and says, “Pen. I love you. And I’ll do whatever you need. But I’m an old man. I can’t keep crashing into Tom. I’ll give you one more take, then we have to move on. End of story.”

That day, Sweetie, whom I was not yet married to — that would come at the wrap party for the Coens’s Miller’s Crossing — and Amy, her younger kid, were visiting the set. Amy was seven at the time. We all had headsets fed from the sound department so we could listen to the acting. We were standing next to Penny, watching the shot on a television monitor, the image fed from the movie camera.

We rolled film, and the actors started the scene. Almost immediately, Elizabeth screwed up a line. The take is no good. It can’t be used in the movie. Loggia has said he won’t fall again. Obviously, we should cut and start a new take. But Penny doesn’t call cut.

“Penny,” I whispered. “Call cut.”

“Huh?”

“Perkins messed up her line. You have no coverage. We can’t use this take.

“Loggia said he wouldn’t fall …”

“I don’t know what you’re saying.”

Sweetie nudges me. “Shouldn’t she call cut?”

The actors continue to walk down the corridor toward the inevitable crash.

“Pen. Call cut.”

“I don’t know what you’re saying.”

Amy whispers to Sweetie, “Mom! Tell Barry to tell that lady to call cut.”

The tension is palpable.

“Pen. Call. Cut.”

“I don’t understand.”

The three actors are about to crash into each other.

“CUT,” I yell.

No one, ever, for any reason, is allowed to call cut except the director. Pen looked at me confused.

“What happened?”

“A light went out,” I said.

We did another take. It went well. It’s in the movie.

The Friday night Big was released I was at the back lot of Universal Studios, visiting Hanks on the set of The ’Burbs. A couple of weeks earlier, when I showed Penny the finished product, the final color-timed answer print, she said:

“I never thought you were a good cameraman. But you picked a nice film stock.”

Now I was in Tom’s trailer, and we were commiserating about Penny’s interview in that day’s Los Angeles Times, where she was quoted as saying she never thought Tom was a particularly good actor, so she made sure to surround him with good actors to make him seem better.

There was a knock at Tom’s door.

“We’re ready for you, Tom,” said the production assistant.

“Are there a lot of good actors out there? I’m not coming out unless I’m surrounded by them.”

At the end of the day, Penny directed a good movie in spite of having to work with a bad cinematographer and a not very good actor.

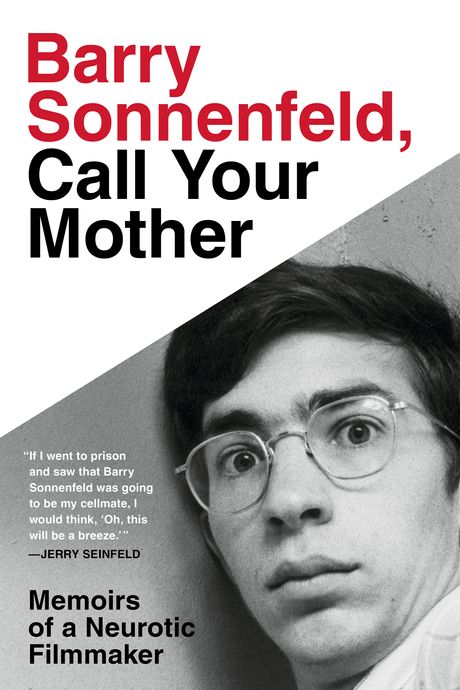

Excerpted from BARRY SONNENFELD CALL YOUR MOTHER: Memoirs of a Neurotic Filmmaker by Barry Sonnenfeld. Copyright © 2020. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.