Obsession runs rampant in “The Case of the Missing Hit,” the latest edition of Reply All’s “Super Tech Support” segment, where the team tries to assist listeners with various internet-related maladies.

To recap: California filmmaker Tyler Gillett was hunting for a song that may or may not exist. The quest started after a holiday party, when he started singing a tune from memory to his wife. He swore it was a hit from the ’90s, some aesthetic mix of U2 and Barenaked Ladies. His wife had never heard of it before. Later, after hours falling down Google rabbit holes, he realizes the song can’t be found on the internet, the infinite repository of information where almost everything that’s ever existed can be found. It feels uncanny, like he’s found a hole in the universe. But the song continues to settle into his brain, an earworm that can’t be cured. Desperately seeking a solution, he reaches out to the Reply All team.

Unlike the mystery track it chases, “The Case of the Missing Hit” is an instant classic. It’s a glorious and unexpectedly thrilling caper, bringing listeners along for a wild ride as Gillett and co-host P.J. Vogt try to figure out the truth behind this spectral single. Is it real? Or is it just a mysterious creation of Gillett’s brain? Their quest takes them to a famed music studio, where they try to re-create the song, and to an assortment of fascinating figures, including a music producer turned neuroscientist, a legendary music critic, and even Steven Page, the former front man of Barenaked Ladies. And all the while, the stakes, which initially feel pretty low, start creeping up ever so slightly, as our protagonists find themselves facing dead end after dead end … all as the earworm deepens its hold in their brains.

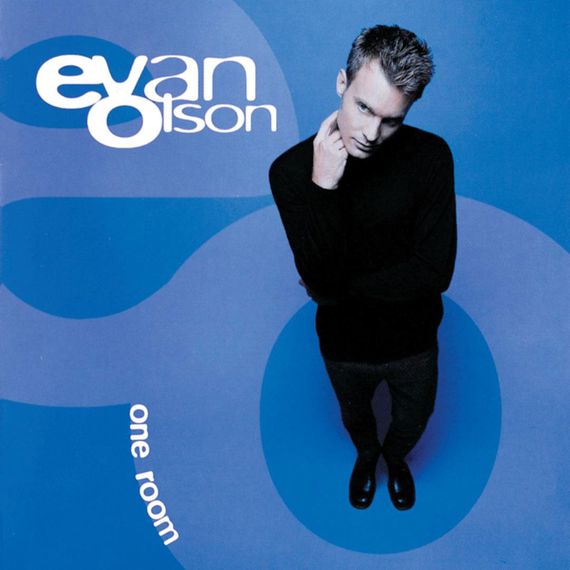

In the end, somewhat miraculously, we find out that the song exists, written by a man named Evan Olson, and that its absence from the internet can be adequately explained: It’s the by-product of a music industry at the height of capitalistic excess and right before it was fully challenged by the internet.

Vulture checked in with Vogt about how the episode came together, the late-’90s music industry, and the general parallel he sees with the modern podcast business.

First of all, did you expect this episode to blow up in the way it did?

I’ve been happily surprised at how much people are enjoying it. I mean, we really enjoyed making it, and as we were working on it we felt like it was going to be a good one that people would like, but I’ve been pretty surprised. Do you have a theory on what’s going on?

Not really. Part of me feels it has to do with a nostalgia for the late ’90s. Part of me also thinks it has something to do with the structure, which has this horror-movie backbone at times. I thought a lot about The Ring and It Follows when I was listening to the episode. You’re given that kind of thrill, but without the stakes.

My best guess is … Well, we say in the story that the song and the desire to find it are contagious, and I think that just turned out to be a little truer than we thought. I also think we dropped it during a week when something that wasn’t a piece of scary news was maybe something people were looking for. I don’t know.

How long did it take to pull this story together?

It was actually a pretty fast turnaround. Our first conversation with Tyler was … let me look. [Checks in-box.] It was on February 16, which means the whole thing took under a month.

Is that abnormal for the show?

Yeah, a little bit. Our stories go all over the place. There’s stuff we’ll work on with varying degrees of focus over the course of a year. There’s stuff we’ll turn around within a few months. So this is a really short amount of time, considering what went into it. The stakes of the story are small, but the reporting was actually pretty deep.

It’s funny — back in the early days of Gimlet, [Reply All co-host] Alex Goldman was working on this very difficult story, and at some point somebody said to him that certain stories just resist being told. And I think it’s true. Those are the stories that are really gratifying to make because you have to invent stuff and try a bunch of different ways to make them work.

This one felt like that, but it had this weird way of feeling the opposite sometimes. Even though it was really hard to find the song, it was a situation where everyone we spoke with was really smart and game and charismatic, and they all had theories that felt plausible and interesting. Whenever we put together a “Super Tech Support,” a lot of them die either because you don’t find an answer or you find an answer very quickly and it’s just not very compelling. And while we’re reporting them out, we’re trying to figure out, “Okay, what else do we get to learn on the way to this answer?”

Was there fear you might have had to scrap this one if you couldn’t find an answer?

Initially, we had the idea that if we didn’t learn anything else interesting from this search, it could have been an opportunity to talk about the concept of the Metaverse. Tyler was actually taking that concept somewhat seriously, the idea that we had fallen in between two multiverses. We even reached out to a quantum physicist from Caltech to talk about it.

Then we quickly realized what we were actually doing was smuggling a short documentary about the late-’90s alternative-rock scene into a quest narrative. And then, when we went into that direction, everyone we talked to was really great. Like, [Barenaked Ladies front man] Steven Page is such a good talker. His descriptions of that era were so vivid and surprising, and it was this thing that I felt a lot of nostalgia for but never really wondered about as an adult. I had never thought to myself, Oh, yeah, this was an industry that was about to be hit by a comet in the form of file sharing and whatever. What was that like?

But, yeah, I feel lucky with this episode. Everybody worked really hard on it. Emmanuel Dzotsi, Phia Bennin, and Damiano Marchetti, who worked production. And also Tim Howard, who is our story editor — he really figures out the narrative bend and shape of a story — as well as sound designer. I feel like he has an ability to create scenes in a story purely through music, and with the parts of this episode where we’re going for that feeling of being obsessed with a pop song so much that it plagues you late into the night, I think he really built a soundscape that captures that feeling.

Could you talk more about what you’ve learned about that late-’90s stretch in the music industry? One idea that the episode evoked really well is how that moment feels weirdly lost to time.

Yeah, I totally feel that way, too. It was interesting. There was some writing we left out of the episode that had this idea where the late ’90s in music was a unique time because it’s the last moment before the internet really shows up. Right now, it really does feel like any kind of music is going to be preserved or documented in some way, even if it’s by accident. Maybe that’s not true, but that’s what it feels like. At that moment, though, it hadn’t happened yet, and the music industry still didn’t know how it was going to be reshaped by Napster and LimeWire and whatever.

I kept joking about how, if we’d had a question about, like, ’80s hip-hop, there would be all these wonderful histories and documentaries and experts. Take your pick, you know? It’s harder to find the “preeminent scholar” of alt rock — it’s not something people venerate very much.

It was nice talking to Steven Page, and hearing him describe what a strange experience it was to be in a band that was really, really popular, but generally considered uncool. And that was kind of all of the music in that era to varying degrees, you know? High success, low canonical credibility.

Yeah, like the Big Pop machine wasn’t really working.

Totally. It’s also funny — while we were working on the episode, we considered, like, “Gee, isn’t it interesting profiling a culture industry at a time after a ton of money pours into it in ways that are both interesting and destructive?” [Laughs nervously.]

Speaking of which, did working the story give you any more anxiety about where this whole podcast thing is going?

It doesn’t give me anxiety in the sense of, like, podcasting is going to go away tomorrow or anything like that. But I did feel like there were parallels. With podcasts in general now, it feels like there are more financial resources out there — it’s even easier for smaller podcasts to monetize now — and I think there’s a lot of people out there getting opportunities for the first time. But there are ways in which it feels like the late ’90s alt-rock-band situation, where there’s a sort of “spaghetti at the wall” thing that can happen.

I mean, you can pour as much resources as you want into an industry, but people’s time and attention and ability to pay attention to a new thing are still finite. And the more stuff that’s in there, the more crowded it gets. I always feel like there’s good stuff out there I’m missing.

Also, podcasts are just time intensive. They feel like you’re starting a new relationship with a new friend. Telling someone that you love a podcast is telling them that you’ve spent hundreds of hours consuming something and they’re going to love it. Pop music isn’t really like that. With a podcast, once you find an audience, they tend to stick with you.

What other shows were you thinking about when you were making this episode?

I thought about Jonathan Goldstein. I thought about Mystery Show. I thought about that old This American Life story about a recording that had something to do with the Little Mermaid [“Buddy Picture,” also by Goldstein], which to me was the invention of this genre — the whole “small stakes investigative quest” thing. That entire episode was about finding this one piece of audio.

I like stories with stakes, but I really do love working on stuff where there’s nothing inherently high stakes. We joke on the show sometimes that Reply All is the SWAT team you call when you lose a penny. Another joke we make is, like, we try to do these small stories where we try to figure out how low the stakes can get while still being enjoyable and entertaining.

Oh, I just realized that another influence was Nathan for You. Like, how can we solve these problems in the most silly and entertaining way we can think of? Strictly speaking, there are probably smarter, less fun plans than recording our own track. But it really did end up being helpful, in addition to just being fun to do.

I was surprised to find that the song was available on Spotify after listening to the episode. Did that happen before or after?

Oh, that was before the episode came out. I was frustrated to find it on Spotify! There was a point in the reporting where I figured I could definitely guess the title, so I kept searching things around “better than” or “you’re better” and things like that. So the fact it’s just been sitting there this whole time made people very vexed.

I’ve been glad to watch his play count go up, though. That makes me very happy.

Were you surprised when you found out the song was real?

At that point, a little bit, but only because I’d been convinced that maybe it didn’t. I think I’m some combination of stubborn and gullible — in a way that does not serve me — and with this story, I was so driven by the idea it just had to exist. I just so much more wanted to believe in a world where Tyler had a photographic memory of a song than a world where he had a normal-person memory, you know? So, sure, there were parts in the reporting where I lost faith, but in my heart I still wanted it to be true.

Have you spoken to Evan since the episode came out?

He sent me an email saying he liked the episode. I’ve been watching his Twitter, and I think he’s really been enjoying watching people discover the song. And he should be! This totally feels like the kind of song that would be on the radio then, so it’s nice for him to see, long after the point where this song would’ve been found by people, that people are finding it right now.

[Update: On Tuesday evening, Olson tweeted that Universal had finally put “So Much Better,” and its corresponding album One Room, back up on Apple Music.]

Last thing: Do you still have the song stuck in your head?

Oh my God. It’s still stuck in my head. Christian Lee Hutson, the musician we worked with to re-create the song, texted me today saying it was still stuck in his head, too. I was walking around the office just like [hums the song], and Phia Bennin, our senior producer, was like, “The story’s over. You’re not allowed to do that any more.”