I realize the world has other, far more important things on its mind — as do I — but I need to get something off my chest.

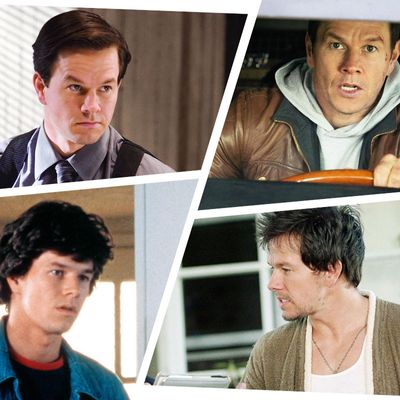

Guys, I’m worried about Mark Wahlberg’s career.

I’ve actually been concerned for several years, but after seeing his new Netflix movie Spenser Confidential (which prophetically went straight to streaming a couple of weeks ago), I cannot stay silent any longer.

First, some context: In the spring of 1995, my senior year of college, I scored an invite to an early screening of a new film called The Basketball Diaries, starring a promising young actor named Leonardo DiCaprio, who had just the previous year been nominated for an Oscar for his turn in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape. After a couple of high-profile supporting turns, this, we were told, would be DiCaprio’s real star moment — the movie that would prove this young performer was here to stay.

Alas, The Basketball Diaries was terrible, and DiCaprio, even though he ultimately would fulfill that early promise, was terrible in it, doing what seemed like a very good impression of an actor doing a very bad impression of Marlon Brando. Instead, what stayed with me from The Basketball Diaries was one of the other guys — a young performer who played one of DiCaprio’s basketball teammates. Here was an explosive firebrand who didn’t have a lot of screen time, but whose genuine intensity pretty much made a mockery of DiCaprio’s actorly indulgences. I soon learned that this young man was Marky Mark, he of the Funky Bunch, whose rap career had blossomed into an underwear-modeling career, which was now becoming a movie career, which was in turn being met with some suspicion by my friends. (“Mark Wahlberg,” they would intone sarcastically, suggesting that his daring to start using his last name was some sort of affectation.)

But I was taken with the actor’s vital sense of menace, that same weirdly dangerous charisma Wahlberg would mine in his subsequent turn as a charming bad boy who seduces Reese Witherspoon and then terrorizes her family in James Foley’s across-the-tracks romantic thriller Fear. It’s not the greatest of films, but the two leads are wonderful in it — you could tell they were both headed for stardom — and Wahlberg is the main reason we keep watching. We can tell he’s up to no good, but we can’t help but be drawn to the guy. We share Witherspoon’s dilemma. It’s not just his hunkiness, though he certainly looks great. There’s something hypnotic about this dude’s presence.

The year after that, Wahlberg would get the break of his life in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights, playing an unassuming, working-class teen who gets roped into the 1970s porn industry and whose stardom waxes and wanes through the subsequent decades. As Eddie Adams, a.k.a. Dirk Diggler, Wahlberg has to go from dim-bulb dreamer to fresh-faced newcomer to eager cokehead to jaded cokehead to weary survivor … and he absolutely nails every part of the trajectory. It’s hard to overstate what a lightning bolt this performance was. Even though the cast was stacked with brilliant performers — including John C. Reilly as Dirk’s blustery best bud and fellow performer Reed Rothchild, Philip Seymour Hoffman as a mousy, closeted soundman, Julianne Moore as a fragile porn star–slash–den mother, Burt Reynolds as a veteran adult director — Wahlberg not only held his own, but he actually seemed to shine more brightly the better everyone else was. A big, bright shining star.

The thing I noticed at the time, and that would become even more evident as the years progressed, was that Wahlberg seemed to feed off the competing energies of his co-stars. Consider the immortal scene (you know the one) where the trio of Dirk, Reed, and Todd Parker (Thomas Jane) attempt to con a shamanically zonked-out drug dealer played by Alfred Molina, who guilelessly terrorizes them with firecrackers casually being tossed around the room by a silent, mysterious companion. The scene naturally belongs to Molina, who dances and gestures wildly and waves a gun around while singing along to Night Ranger’s “Sister Christian” as our three heroes sit on the couch, trying not to lose their minds. There is, eventually, a gunfight, but the emotional climax belongs, as it must, to Wahlberg, who in the middle of the madness gets a 50-second-long close-up — an eternity in modern moviemaking — in which he does, well, nothing. He doesn’t speak or react; he just kind of stares into the distance, at first coked out and defiant, then vulnerable and anxious and finally self-aware, as if emerging from a years-long mental fog into a moment of clarity. Gradually, we understand that we are watching a genuine turning point in this young man’s life. One could argue that without Molina’s flamboyance, this extended moment of restraint wouldn’t work at all. Which is true. But without Wahlberg’s close-up, the scene would have no anchor. He gives the entire sequence its humanity.

After Boogie Nights, Wahlberg was off to the races, with parts in a couple of dreadfully sleazy but financially successful action films (The Big Hit, The Corruptor), as well as more ambitious dramas that called on him to play beleaguered heroes (The Yards), ignorant but ultimately compassionate grunts (Three Kings), and earnest romantics (The Perfect Storm). Cops, soldiers, fishermen, crooks with hearts of gold, and, later, athletes, bartenders, firemen … This is the dramatis personae of Wahlberg’s career, and he’s stuck to it with admirable consistency over the years. Such parts capitalize on Wahlberg’s working-class charisma, and on the idea of an ordinary person caught in extraordinary circumstances. Which makes some basic sense. The actor came from modest roots and got involved in drugs and gang activity in Boston at a young age. His troubling real-life backstory includes horrific acts of racist violence and a stint in jail; he was a tough kid who fucked up early and often. (But somehow, he was also briefly in New Kids on the Block, alongside his brother Donnie? One day, somebody will make a real movie about Wahlberg’s life, and it’ll be fascinating.)

Wahlberg’s attempts at outright blockbuster star vehicles during the initial phase of his career often ended in dismal failure. The Tim Burton Planet of the Apes would probably have been a dud even if the lead wasn’t completely lost, but he sure didn’t help matters. The comic-book flick Max Payne was just ghastly on every level. He was comically miscast in M. Night Shyamalan’s The Happening, in which he was somehow asked to play a science teacher. He was also totally wrong for Jonathan Demme’s Charade remake The Truth About Charlie, stepping into a role originally intended for Will Smith, but Demme realized the mistake early on and turned the film into an ambling, free-form love letter to Paris and to the French New Wave. The resulting movie is underrated, but Wahlberg’s still a problem.

During this time, however, Wahlberg had a string of supporting parts that demonstrated his talent, and also proved how effective he could be when cast against the right actors. In David O. Russell’s I Heart Huckabees, he’s an existentially conflicted fireman whose earnestness contrasts sharply with Jason Schwartzman’s hipstery interiority; indeed, it’s one of the film’s themes, as we learn that the two are cosmically connected as “others.” (Don’t ask; I still can’t quite believe that movie exists.) In Martin Scorsese’s The Departed, for which he was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar, Wahlberg steals the show right out from under the likes of DiCaprio, Matt Damon, and Jack Nicholson as a pissed-off, motormouth staff sergeant who, unlike his mild-mannered superior Martin Sheen, loves hurling rapid-fire insults at those under him. In James Gray’s crime drama We Own the Night, he plays the stern, loyal police-office brother of hedonistic nightclub manager Joaquin Phoenix. Without Phoenix, Wahlberg would just feel like a stick in the mud. But without Wahlberg, Phoenix would feel like a bit of an overreacting clown. (You know what Joker could have used? A part for Mark Wahlberg. [Ducks.])

The year 2010 found Wahlberg starring in two of his best movies. In Russell’s The Fighter, his submerged energy as a down-and-out prizefighter works marvelously against Christian Bale’s demented, Oscar-winning turn as his crackhead brother; the wilder Bale is, the more Wahlberg looks like he wants to disappear into his shell forever, which just happens to be the central dynamic in this story of a boxer struggling to get out from under his overbearing, toxic sibling’s broken dreams. In Adam McKay’s The Other Guys, one of the great comedies of our time, Wahlberg is a hilariously frenetic, disgraced cop forced to work with Will Ferrell’s straight-arrow pencil pusher. Again, in both of these movies, Wahlberg works best as part of a two-person ecosystem, playing off and grounding the more stylized performance of his co-star. In 2013’s heist-gone-wrong flick 2 Guns, the roles are reversed: Wahlberg is an over-the-top, wise-cracking, loose-cannon Navy intel officer, while Denzel Washington plays the brooding, betrayed DEA agent with whom he partners up. Their chemistry is irresistible. As I wrote in my review at the time, “You never want to see them apart, and whenever they’re separated, the movie loses energy.”

I think Wahlberg understands, on some level, that he’s at his best when working off a co-star who can be the things he’s not, and vice versa. That would explain the Daddy’s Home movies (he’s actually terrific in the first one), which co-star his Other Guys compadre Ferrell, but it doesn’t quite explain his couple of not very good Transformers films; I think money explains those, and Wahlberg, who’s involved in a lot of different businesses, has never had any shame about admitting that he likes to get paid (a fact that got him in some deserved trouble when it came time to doing reshoots on Ridley Scott’s All the Money in the World, making the actor a poster boy for the gender pay disparity in Hollywood). There’s even a brief bit in the Entourage movie, which he produced, and which was based loosely on his own experiences as a rising star in Los Angeles, about how he’d make financially lucrative Ted movies until the end of time if he could.

It’d be easy to say that as the movie industry was dominated by franchises and tentpoles, Wahlberg gravitated, like many others, toward the empty-calories blockbusters that didn’t really put his talents to much use. But that’s not entirely true, is it? Over this period, he’s made a number of based-on-real-life, non-sequel action dramas with director Peter Berg: Lone Survivor (which was a huge, controversial hit), Deepwater Horizon (which is, believe it or not, Berg’s masterpiece), and Patriots Day (which I can’t remember at all, frankly). Whatever you or I may think of them, these pictures are clearly deeply meaningful to the actor. The films, in which Wahlberg plays such typically Wahlbergian roles as a soldier, an oil-rig worker, and a cop, speak to the actor’s roots, and to the self-image he’s been trying to cultivate, that of the working-class maverick with a moral center. These roles and others may even be part of his attempt to reconcile the person he is now — by all accounts, a devout, disciplined family man — with the troubled punk he used to be. (He has even, at times, confused this idealized, movie version of himself with reality.)

When I saw that Wahlberg was going to be in Spenser Confidential, based loosely on crime novelist Robert B. Parker’s beloved Spenser series, I was elated. The Berg-Wahlberg docu-action-drama genre had run its course, and it seemed like the role of a private detective, a disgraced cop and ex-con trying to uncover a vast criminal ring on the mean streets of Boston, might have returned the actor to that sweet spot where he could play off the energies of a variety of different performers, particularly the excellent Winston Duke as Spenser’s roommate/partner Hawk. It might have been a nice reset for Berg, too. And while Spenser Confidential isn’t an abomination, Berg’s limp, montage-happy direction doesn’t do anyone any favors, and Wahlberg lacks that vitality that used to be such a key part of his acting arsenal. Still, the film has its moments and it’ll pass the time, which might be all that’s required at this point in our lives.

And yeah, I feel like something has been lost. I miss Mark Wahlberg the hothead, the unpredictable live wire of The Departed and The Other Guys and Three Kings and 2 Guns (and, yes, The Basketball Diaries). I also miss the earnest Mark Wahlberg of I Heart Huckabees and The Fighter. As he proved over and over again during that golden period when he was one of our most exciting actors, he is capable of so much more. The question is whether he, like movies in general, will be willing to take some risks again.