When Terrence McNally won his 2019 Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement, he received the honor smiling, laughing — and breathless. A plastic tube snaked under his nose; an oxygen tank hung at his side. He had survived lung cancer and lived with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, so he had built himself a speech of short lines, almost epigrams. It was a beauty. Little breath by little breath, he recalled his own debt to the playwrights club (“the dues are your heart, your soul, your mind, your guts”) and his gratitude at his ability to move others — particularly the parents of gay children who had come out of the closet — to understanding and greater kindness. He died on Tuesday at 81 of complications from the coronavirus. In that 2019 speech, he had opened with a joke. “Lifetime achievement,” he said, dryly. “Not a moment too soon.”

McNally’s much-awarded work spans the last five decades of American drama, but for some of us, it also spans our lives in the theater. Many encountered his plays and musicals at the inflection point that cast us into wild love, the kind we couldn’t get out of. The best of his dramas were spiky, adult, and accessible; the books he wrote for musicals like Ragtime and Kiss of the Spider Woman were frankly erotic and seductively candid. When I first encountered the plays in college, he struck me as an American Chekhov, funny and wry while also being deeply humane. Those gateway dramas were, for me, Lips Together, Teeth Apart (I built a set for it that included a pool that both leaked and grew algae), Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune, and then on the page, Love! Valour! Compassion! — his dramatic magnum opus, a three-hour-long estate tragicomedy in the (first) era of AIDS. Delighted by these plays at 20, I was excited by all the nudity, the Elaine Stritch jokes, the sex, and their laughter-amid-tears grandeur. Now, though, in middle age, I realize they burned their way into my life because of their moral clarity. These are Great Shouts about death and age and disappointment and disease. How did I ever think they were gentle?

Because, says Lincoln Center Theater’s producing artistic director, André Bishop: “He managed to slightly shock people and to charm people, and I think those two qualities were very much in Terrence and in his work.” The writing wasn’t just intelligent — it was meant to reach a wide audience. “He was not a man afraid of being popular or being a success,” says Bishop. “He loved that and rightly so. And yet he also wrote from a point of view of seriousness and earnestness and deep feeling.” In the catalogue of plays that we all remember McNally for — Master Class, The Lisbon Traviata — few are mentioning the ones closest to Bishop’s heart. He talks, for instance, about Andre’s Mother, McNally’s 1988 play (later an Emmy Award–winning teleplay) about a mother who can’t accept her dead son’s lover. As he did in every play, McNally wrote from a position of sympathy, even for those who couldn’t put aside their bigotry. “There was always this warm human being underneath all that sophistication,” Bishop says, tying McNally’s craft to his quality as a person. “I know a lot of warm human beings, and I know a lot of funny, witty, sophisticated people — I just don’t know a lot who are both.”

In a wide-ranging conversation with Annie Baker, filmed for the Dramatists Guild at McNally and husband Tom Kirdahy’s apartment, McNally spoke about what drew him into the arts — a passion for opera. What did he love? “The emotions, and that people wore their hearts on their sleeve,” he said. “I like frank emotional stuff.” He liked it so much that he was able to outlast the viciousness that met his first produced play And Things That Go Bump in the Night, which, implausibly, went to Broadway. It was 1965, he was barely out of Columbia, and here was a brainy play full of honest depictions of gay life, with characters who had sex and weren’t “there to commit suicide or provide comic relief.” It lasted 16 performances. (For the rest of his life, he could quote his worst review: “The American theater would be a healthier place today if Terrence McNally’s parents had smothered him in the cradle.”) In 1967, though, he put his play Next into the hands of Elaine May. Produced Off Broadway, it was a hit, and he credited May’s direction for his career — he was able to make a living writing plays from then on — and teaching him to write. Much has been made over the years of his seven-year relationship with Edward Albee, and McNally himself said while speaking with Baker that you can feel Albee’s stamp in And Things …, written before the young playwright fully found his own feet. But eventually he drew away from that mighty influence: May taught him to write action — and his own keen ear for voices carried him the rest of the way.

His populist sensibility meant that his work often made it into the mainstream, where it often did real, quantifiable good. Tony Kushner remembers his parents going to see the film of McNally’s farce The Ritz in the 1970s when Kushner was still in high school. “My father wasn’t a virulent homophobe,” says Kushner, “but he was upset when he figured out I was gay. When he saw the film with my mother, he said he liked the movie a lot and that it was making a plea for tolerance for homosexuals. He said, ‘It makes a very moving case,’ and that was a big deal for me. It was the only time that he hinted that there might be some … accommodation. I’ve felt a great gratitude to Terrence for that.”

McNally also wrote for five decades without painting himself into a single style. “I think that in all of his plays, there’s a real ambition to both push the boundaries of what theater was doing and an ambition to re-create himself,” says Kushner. “He was a bit of a chameleon trying out new forms and new shapes. I was always in awe of the superabundance of Terrence’s imagination — it was a fountain of plays and ideas and plots and books for musicals. Speaking as somebody slow and miserable like me,” Kushner laughs, “I was always astounded by the level of constant invention.”

In fact, McNally’s success can sometimes, paradoxically, cloud our view of him. He thrived in the commercial theater, and he wrote well-made plays and musicals, which has meant that scholars and critics have sometimes given him short shrift — even as his work inspired countless other playwrights and bewitched audiences. “When we watched the recent revival of Frankie and Johnny,” says Kushner, “it was exciting to see somebody’s work with that sense of absolute craft. There’s a shape and a responsibility there: ‘I, the playwright, am going to take care of the audience. Follow me.’”

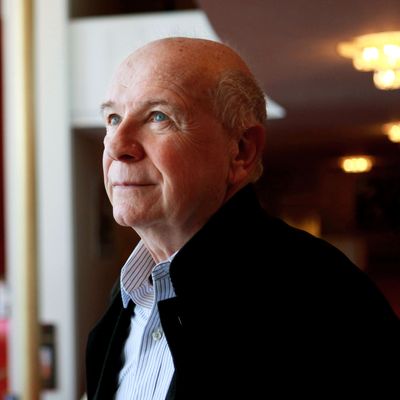

Lynne Meadow is the artistic director of Manhattan Theatre Club — the organization that in 14 years produced 14 of his plays. “We were his artistic home,” she says. Meadow has been emailing and calling those who loved him, and it seems as though that includes every playwright, every artist, he ever encouraged. “Joe Mantello wrote to me saying, ‘We’re lucky,’” says Meadow. “And yes! We’re lucky and very proud. His plays will be done; he will be celebrated. And he loved to be celebrated. He did!” When we spoke, her mind was racing with images of working with and knowing McNally—the huddled conferences after previews, the phone calls in which you could hear opera blasting away on the other end. But she ended with an early memory. “In 1972–3 at Manhattan Theatre Club, I did 23 plays in seven weeks,” she says. “The highlight was Terrence McNally’s play Bad Habits. I was 24 or 25 years old; it was my first season. And I’ll never forget seeing him walking in with Bobby Drivas, who was going to direct it, with his Shetland sweater knotted around his neck, so very preppy. He was so adorable, so arrogant! He looked just like a Columbia student who had just written the Varsity Show, which of course he had. I had no idea what a role he would play in the American theater.” She pauses. “I just remember that sweet face.”