When Lawrence Wright first read about the outbreak of a deadly new virus in China, a strange and unsettling feeling came over him. “I had a sense that what I had written was about to unfold,” he recently recalled. Wright is best known as a journalist, but he had spent the past several years researching and writing a novel. Set in the spring of 2020, it tells the story of a fictional virus that originates in Asia and rampages across the world, overwhelming health-care systems, forcing schools to close and citizens to shelter in place, and plunging the global economy into ruin. At one point, a government official informs a colleague that the United States only has enough ventilators to accommodate a fraction of the people who need them. Watching each of these events play out in reality, Wright experienced “a kind of astonishment,” he said. “When I was writing the novel I thought it might happen one day,” he said, “but I didn’t think it would happen today.”

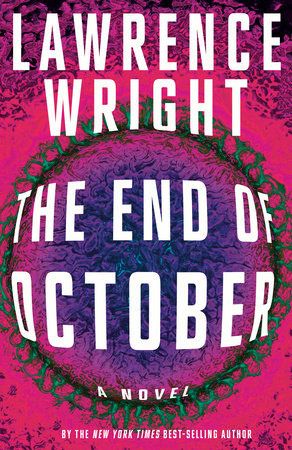

The End of October will be published later this month, two weeks earlier than initially planned. Other titles have been delayed by the crisis, but Knopf has elected to get The End of October into the hands of the homebound reading public as quickly as possible, noting the uptick in sales of classic pandemic narratives like Albert Camus’s The Plague and Stephen King’s The Stand. “I’m being called a profiteer,” Wright told me the other day, speaking on FaceTime from his book-lined home office in Austin, Texas. The Telegraph, he noted dryly, had recently written that The End of October “may be the only book to benefit from being launched while coronavirus spreads.” His friends, meanwhile, had been ribbing him about being “a prophet” — an epithet that the modest Texan dismissed with a good-natured chuckle. “I don’t see myself as a prophet or even particularly prescient,” he said. “The question that journalism normally asks is, ‘What happened?’ Our skill is to go out, and talk to people, and check their facts and try to understand it ourselves so we can explain it to our readers. It’s not a very big step from that to say, ‘What could happen?’”

Wright may not be a prophet, but he does have what his boss, David Remnick, the editor of the New Yorker, calls “an unerring instinct for the big story.” Pandemics “were hardly a secret,” Remnick wrote in an email, “and many others have been warning about something like COVID-19 for a long time. Larry clearly set out to dramatize that warning in the shape of a novel. And then everything happened — too soon, too horribly.” It would be easier to write off the book’s eerie verisimilitude as a function of pure coincidence if Wright hadn’t done something like this once before. In the mid-’90s, the producer Lynda Obst hired him to write a screenplay, stipulating only that it had to be about a woman in the CIA. He approached the challenge as a reporting assignment, interviewing a range of agents and intelligence experts who told him of the dangers posed by Islamist terrorism, a threat that was far from the forefronts of most peoples’ minds at the time. The film, The Siege, which depicted a series of terrorist attacks on New York City, was a box-office failure, but three years after its release, in the wake of 9/11, it became the most rented movie in America, Wright says. In an interview with CBS in 2007, Wright described the sensation of watching the September 11 attacks unfold on TV: “People said, ‘You know, it looks like a movie,’ and I was thinking, ‘Yeah, it looks like my movie.’”

The plot for The End of October came to him after a conversation with the director Ridley Scott about a decade ago. Scott, who was interested in collaborating with Wright on a film, had recently read The Road, Cormac McCarthy’s relentlessly bleak novel about a father and son struggling to survive in the wreckage of an unspecified global cataclysm. Fires have consumed forests and cities; money has lost all value; governments have fallen; cannibalism has taken hold. Scott challenged Wright to write a script inspired by the unanswered question that hangs over McCarthy’s story. As Wright put it: “What would it take to cause our civilization to fracture?”

Wright considered nuclear war and terrorism — the obvious culprits. (The perils of climate change, he pointed out, were not as widely understood as they are now). But then he thought back to the beginning of his career, when he’d reported on the outbreak of swine flu at a military base in 1976. He’d been impressed by the bravery of the health-care workers and scientists he’d met. “They were swashbuckling intellectuals, a combination you don’t always find, and they’d charge into places that are terribly, terribly dangerous,” he recalled. If the heroes of those battles largely went unrecognized by the public, so did the foes they were battling against. “Diseases are a kind of invisible enemy,” he said. “They don’t announce themselves until they suddenly spring onto the stage.” In part, this was a result of our hubris. “The 20th century was all about overcoming the diseases of history,” Wright said, “and we did such a great job of it. But nature has not stopped creating new forms of diseases. It may be that disease is our greatest enemy, but we’ve set it aside because we’re so focused on our human adversaries.”

Wright sent Scott a script about an epidemiologist trying to stop the virus’s spread and find a cure, while his family struggled with the disease’s terrible fallout. Scott didn’t end up making the film, but Wright couldn’t shake the scientists he’d talked to while researching the story — how alarmed they were about the possibility of a civilization-cratering pandemic. It reminded him of conversations he’d had with counterterrorism experts while researching The Siege. In both cases, Wright said, “there was a level of anxiety that I had totally not expected.” He decided he’d turn his script into a novel, and immersed himself in research once again.

Wright is known for his exhaustive and meticulous reporting. His best-known work, The Looming Tower, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 2007, is the definitive account of the rise of Al Qaeda. To construct the gripping narrative, he interviewed more than 500 sources, including Osama bin Laden’s best friend in college. (It has been said that he knows more about Al Qaeda than many people in the CIA or the FBI.) For The End of October, he spoke with some of the foremost virologists and epidemiologists in the world, leaders of disease-fighting squadrons at places like the National Institute of Health and Ft. Detrick, the military laboratory that was once the center of the United States’ biological weapons program. Barney Graham, the deputy director of the Vaccine Research Center at the N.I.H, told me he agreed to help Wright because he hoped that the novel would help educate people about the need to prepare for a pandemic. “It is hard to imagine the reality until you live through it,” said Graham, who is now racing to develop a vaccine for COVID-19. Another source, Dr. Philip R. Dormitzer, the chief scientific officer at Pfizer Vaccine Research, added that he hopes Wright’s novel would spawn a new genre of thrillers. “Stories in which a middle-aged, workaholic virologist is the hero are in short supply,” he wrote.

Reading the book now, amid a pandemic that has exposed the terrifying fragility of our social structures and political institutions, is a deeply unnerving experience. Wright’s virus, the Kongoli flu — a deadlier illness than COVID-19 — sweeps around the world, unleashing a chain of dystopian horrors. Food grows scarce, governments collapse, a cyberattack takes down the internet, and war breaks out between the U.S. and Russia, dragging the world into a new dark age. “Little was left of modernity except for weapons,” Wright narrates in his plainspoken, reporterly voice. When I read a passage that explained how the run on ATMs made it nearly impossible for a character to buy groceries, I thought about the 23 dollars in my wallet and made a mental note to take out more cash. Wright told me he’s experienced something similar. While he was writing, he set up a calendar on his computer to keep track of his characters’ movements as the virus spread around the world, and although he’s tried to delete it, the reminders, uncannily, still pop up from time to time. At the beginning of March, while the city of Austin was still debating whether or not to cancel South by Southwest, Wright thought of his protagonist, the epidemiologist Henry Parsons, telling his wife to stock up on groceries and prepare to hunker down. He ordered seeds and planted lettuce. “I was taking a note from my hero that we should do the same,” he said.

Henry eventually stumbles onto the early stages of a vaccine, and succeeds in tracing the virus to its surprising origin. But the world is nonetheless fundamentally transformed, and not for the better. “I wrote the book in a period of national desolation. America is in decline, our politics have become so contentious, we’re paralyzed as a nation,” Wright said. “And so the book reflects that attitude. And frankly, by the end of the book, the country doesn’t succeed in meeting the challenge.”

These days, as Wright shelters in place at his home in Austin, playing piano at night with his daughter and son-in-law, he’s hoping for a better outcome than the one he imagined. “We have a moment of opportunity to do a cultural reset that could lead us to a better time,” he said, sounding a bit wistful. “The Black Death led to the Renaissance. It ended the Middle Ages. It liberated the mentality of humankind. I don’t know what will come of all this,” he added, “but I think it’s still in our hands.”

The End of October is out April 28.

More on Coronavirus

- Lil Wayne Gave More Than a Li’l Covid Relief Money to ‘Mystery Women’

- Andrew Cuomo Can Keep $5 Million for COVID-19 Book, Judge Rules

- Who Dares Talk Back to Patti LuPone at a Patti LuPone Talk-back?