Over the next five weeks, ESPN will give a glorious gift to a sports-deprived public.

That gift is The Last Dance, a ten-part docuseries about the rise of Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls that pays specific attention to their 1997–1998 season, when the team won its sixth NBA championship and brought one of the most dominant reigns in modern sports history to a close. The television event was originally scheduled to debut in June, no doubt with an eye toward maximizing promotional opportunities during this year’s NBA playoffs and finals. But with no NBA season and no professional athletics of any kind during the coronavirus pandemic, ESPN decided to move the release date up to April 19. Look, it was either that or air indefinite reruns of the socially distanced NBA/WNBA HORSE competition. The right choice was obvious.

The Last Dance would have been a great, widely consumed sports-umentary under any circumstances. But in the odd, trying times Americans and people around the globe are experiencing, it will be revered as a dunk- and drama-filled oasis in a time of drought. The series effectively ticks a number of boxes that audiences desperately need to be ticked:

1. It gives people something to watch and, with two hour-long episodes landing every Sunday from this week through May 17, something they can look forward to at the end of every long, long week.

2. It provides content that’s both sports-related and new, albeit driven by looking to the past.

3. It taps into a deeply nostalgic vein for anyone who followed Jordan and the Bulls, or just misses the 1990s. On the ’90s flashback front, The Last Dance has it all: oversize blazers galore; footage of Jordan shooting Nike commercials with Spike Lee; footage of Jordan shooting the movie Space Jam; montages of the Bulls killing it on the court to the music of Prince, Run-D.M.C., Soul Coughing, and Blahzay Blahzay; and even footage of Jerry Seinfeld visiting M.J. in the locker room. (“This is not going to work, by the way,” Seinfeld jokes as he leaves, pointing to a play on the chalkboard. I’m pretty sure Phil Jackson did not take note.)

4. It gives everyone a docuseries to experience and discuss that isn’t Tiger King. 🙌

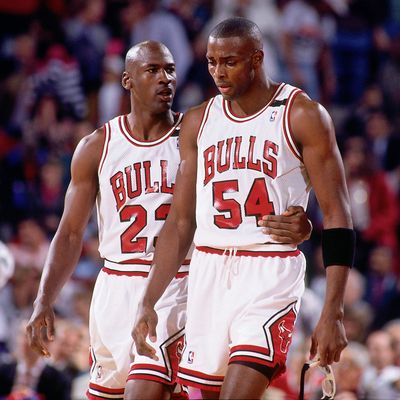

The Last Dance is wide in scope. Over its ten hours, directed by sports documentarian Jason Hehir, it tracks the Bulls’ climactic path toward a sixth championship but also slides backward in time to explain the history of how Michael Jordan went from UNC Tar Heel to NBA icon and one of the most famous people on planet Earth. It also traces the evolution of the Bulls in the late ’80s and ’90s, tells the story of Scottie Pippen, and revisits the emergence of Dennis Rodman as a skilled Chicago Bulls defender and pop-cultural oddity.

Like O.J.: Made in America, another ESPN production, The Last Dance goes long and deep on its subject. Unlike that Oscar-winning project, this one doesn’t delve as much into the racial and sociopolitical issues that the arc of Simpson’s story naturally raised. Hehir, who spent eight hours conducting new interviews with Jordan, as well as others, and had hours upon hours of behind-the-scenes footage of the Bulls’ swan-song season, shot by NBA Entertainment, does offer a more complicated and candid portrait of the famously private Jordan than we’ve seen before. If you ever admired Jordan — is there anyone who didn’t? — followed the Bulls, or just like basketball, it’s must-see television.

The first episode of the docuseries recounts how Bulls general manager (and Jordan nemesis) Jerry Krause told Phil Jackson at the beginning of the 1997–98 season that this would be his last season as head coach, prompting Jordan to announce that if Jackson didn’t return, he wouldn’t either. Knowing in advance that the next several months would mark the likely end of a dynasty, Jackson dubbed the season “the Last Dance,” and made its mission instantly clear: The Bulls would aim to win a third consecutive championship and sixth overall, an unprecedented three-peat.

From there, the timeline of the series shifts backward and forward and interweaves footage of old games, news coverage, and interviews providing context about all the history being relayed through a variety of sources — including Jordan’s mom and brothers, numerous NBA players, former NBA commissioner David Stern, journalists, and presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama (initially identified as “former Chicago resident”). The major events from this period are all covered: the impressive championship wins, the rivalries with the Detroit Pistons and the New York Knicks, Pippen’s triumphs and frustrations with management, the Dream Team, the murder of Jordan’s father and its impact on the icon, Jordan’s temporary retirement and brief pursuit of a baseball career, and the wild hair and habits of Dennis Rodman. (Note to whomever: I would happily watch a docuseries that focuses solely on Rodman’s brief romance with Madonna.)

What emerges more and more as the episodes progress is just how intense Jordan is, not just on the court but off of it as well. There was speculation at one time that he had a gambling addiction — The Last Dance covers that, too — but what Jordan admits to being addicted to above all else is winning. What seems to have fueled him more than anything was spite. In just one example of many, Jordan says he focused hard on outmaneuvering Phoenix Suns’ Dan Majerle in the 1993 NBA finals simply because Jerry Krause — whom, and this cannot be overstated, Jordan could not stand — thought Majerle was a good defender. “That was enough for me,” Jordan says.

The dude can also hold a grudge until he practically strangles it. He’s still irked by the fact that the Detroit Pistons, including Isiah Thomas, walked off the floor without shaking hands after the Bulls beat them in the 1991 Eastern Conference Finals. Hehir hands Jordan an iPad so he can watch the interview with Thomas, done for this documentary, in which the former player downplays the significance of the non-hand-shaking. Before he even looks at it, Jordan scoffs. “You can show me anything you want. There’s no way you can convince me he wasn’t an asshole.” Watching Jordan react to other interviews is one of the joys of this experience. (This seems like a good place to note that ESPN will air an uncensored version of The Last Dance, in which salty language, including F-bombs, abound, while ESPN2 will show a version in which that language is edited out, for those who plan to watch with kids.)

Jordan’s image, which he and his managers carefully cultivated with shoe lines and commercials to create a brand that remains viable today, has always been polished, though it has certainly gotten some, ahem, knicks in it over the years. But it’s still rare to hear people, including Jordan himself, admit to just how difficult he could be, at least on a network like ESPN.

“Let’s not get it wrong,” says Will Perdue, who played alongside Jordan on the Bulls from 1988 to 1995. “He was an asshole. He was a jerk.” Then he adds: “As time goes on and you think back on what he was trying to accomplish, he was a hell of a teammate.” That echoes what several of Jordan’s teammates say: They didn’t necessarily love him, but he made them better.

At one point, in episode seven, Jordan acknowledges that viewers watching The Last Dance may conclude he was a tyrant. “I don’t have to do this,” he says, a reference, it seems, to being interviewed for the docuseries. “I’m only doing it because it is who I am. That’s how I played the game. That was my mentality. If you don’t want to play that way, don’t play that way.” He starts to tear up, at which point he says: “Break.”

The point of The Last Dance isn’t to sully Jordan’s reputation. It is, among other things, to show us that even a man often thought of as the GOAT of basketball, and maybe sports in general, has flaws and struggles he still reckons with, long after having retired. By taking us back to that period when the Chicago Bulls were practically untouchable and Michael Jordan was considered a god among humans, it also reminds us how it felt the first time we saw greatness, in the form of a man, his tongue sticking out like a little boy’s, taking flight over and over, right before our eyes.